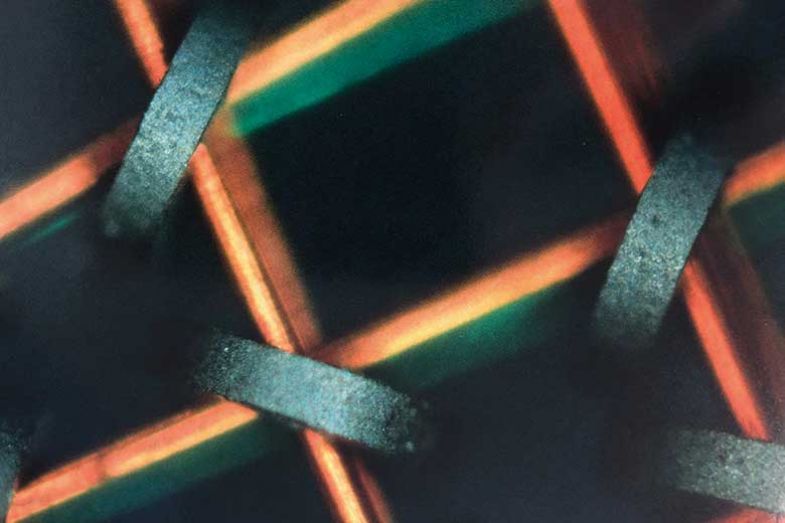

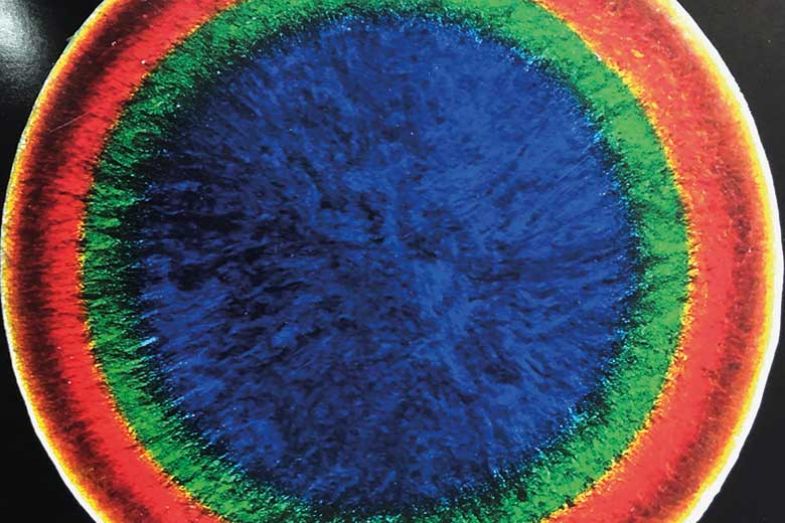

The image above shows a ferrofluid, a colloid of small iron filings suspended in oil. Below is a close-up, seen through a microscope, of the memory core of an IBM computer from the mid-1960s. Each tiny, doughnut-shaped magnet held a single bit of information. Below that is a block copolymer, just a centimetre in diameter, suspended in a solvent between two pieces of glass. When the solvent evaporates around the edges, the polymers reassemble and go through dramatic colour changes.

These images are all taken from a spectacular new book, Felice C. Frankel’s Picturing Science and Engineering (MIT Press). Intended as an act of homage to “the women and men in science, engineering, and medicine who are solving the most challenging problems of our planet”, it is both a brilliant demonstration of just how photogenic science can be and a guide to taking similar pictures.

Frankel starts with the seemingly unpromising flatbed scanner and demonstrates how it can “help you create some very fine images of three-dimensional objects, like microfluidic devices, Petri dishes, and other sorts of material you might fabricate or work with in the lab”, while resolution control can bring to the surface all sorts of amazing detail invisible to the naked eye. From there she moves on to basic camera techniques, light sources, phone cameras, microscopy, image adjustment and enhancement.

But while the book is a visual treat (and includes a brief digression about some particularly photogenic meals that Frankel has eaten), it also makes an important argument. Scientists wanting to communicate with and impress their peers now need to take great care over their slide presentation, not to mention any images that they hope will appear on the cover of a magazine. Furthermore, writes Frankel, “smart, accessible, and compelling representations of science can be doors through which others can enter”, thereby adding to the vital scientific literacy of society. She even suggests that “part of a researcher’s education should be to develop ways to look , and then to understand”. Picturing Science and Engineering makes her case in the most seductive possible way.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?