There should be a copy of this important, occasionally sensational and highly entertaining book in every Welsh library, as well as in the collections of anyone with an interest in the creation of enjoyably patriotic, but largely spurious, national identities. For despite its sensational title, this is not entirely a book about Druids. A more accurate title would be "The Creation in London of a Welsh National Identity, by Iolo Morganwg and Tony Blair".

Ronald Hutton's scholarship is not only breathtakingly thorough but also ruthlessly critical. In his first chapter, questing after reliable information on the Druidic identity, he works through 18 ancient authorities, from Julius Caesar to St Patrick, and casts withering doubt on each of them. This leaves the reader wondering whether Druids existed until the 18th century. Are they simply an idea waiting for unscrupulous eccentrics to shape them into their own obsessions - kindly, nature-loving monotheists with a tendency to burn victims alive in wicker baskets?

What is so shrewd about Hutton's historical analysis is his perception that the Tudor period was culturally disastrous for Wales. Before the Tudors, a bardic culture was flourishing, but once the Welsh took over the new British superstate with a potent royal dynasty, and a Church of England legitimised by memory of a pre-Augustine native Celtic Christianity, the Welsh became part of an English Establishment with nothing to rebel against. There were no more feudal bards with a native literary tradition. London became an ambitious Welshman's goal and it would be London Welsh, with their Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, and more radical Gwyneddigion, who relaunched the bardic tradition in 1792 at the summer solstice on Primrose Hill.

Central to this London movement was a brilliant liar and forger of bardic material, Edward Williams, known to his new nation by his bardic title Iorwerth Morganwg ("Glamorgan Eddie"), or Iolo for short. The political ambivalence of this London Welshness is summed up by Iolo's favourite toast to "the three securities of liberty: All kings in Hell; the door locked; the key lost". Yet a patriotic new verse was added to God Save the King at that 1792 gathering, praising "George and Britannia's laws". The Welsh middle classes never really swim politically; they keep one foot nervously on the sea floor. There was sympathy in 1791 for the French Revolution, but disclaimers for its excesses.

England's royalty has always played a clever game with its princes of Wales. But it was George II's wife, Queen Caroline, who made Druids fashionable in 1735 when, schooled by the German pansophist philosopher Gottfried Leibniz, she asked William Kent to design a multi-domed cave for Merlin, the Archdruid, in Richmond Park; Princess Victoria attended the 1834 Cardiff eisteddfod; and Prince Philip is bardically Philip Meirionnydd. Archbishop Rowan Williams, too, is a Druid, Rowan ap Neirin, but not inclined to burn religious rivals.

The real appeal of Druidry was its belief in reincarnation, the transmigration of souls. That left the way open to all manner of left-wing faiths: universalism, Unitarianism, theosophy. Iolo was often high on opium as he forged medievalism to justify the rituals that make all national eisteddfods so harmless: blue robes for Bards, white for Druids, green for Ovates, mixed colours for Awenyddion (bardic disciples).

The real riches of this rewarding book lie in its middle chapters, where a string of confident South Welsh eccentrics launch the Pontypridd Rocking Stone as a pulpit for successful eisteddfodau. Matthew Arnold might have complained at the 1864 National Eisteddfod in Llandudno about "our hideous 19th-century costume" and declared: "we all of us, as we stood shivering round the sacred stones, began half to wish for the Druid's sacrificial knife to end our sufferings", but the Welsh are not a pompous people, and they enjoy the ridiculous. One ancient British chief made a robe for himself out of the beards of tyrants; one of the Crawshay family of Merthyr Tydfil ironmasters had 24 bastard children and named the streets of his industrial housing after them.

The Welsh National Anthem - Mae Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau - was launched from the Pontypridd Rocking Stone, and from it, in 1851, mercenary bards were cursed to Annwn (Hell) and Lucifer's personal water closet.

English and Scots may be competitive, but English and Welsh are an item, laughing and interacting. This is a serious book about an essentially humorous and human movement: New Age Glastonbury with just a touch of Nazi Nuremberg. Albert Speer would have approved of the new Welsh National Assembly's stark simplicity, as A.W.N. Pugin would have loved the new Scottish Parliament. Nationalism has its rich cultural variations; here we can delight in them.

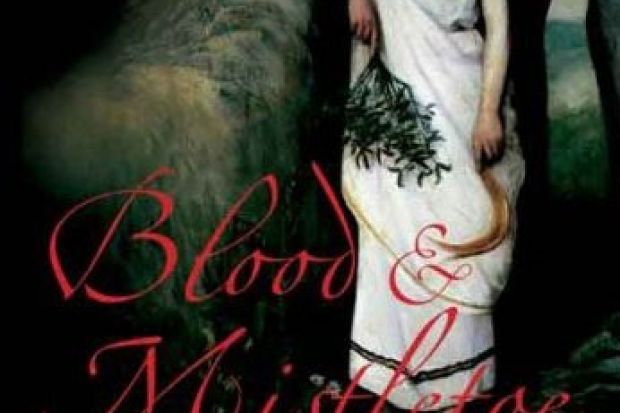

Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain

By Ronald Hutton

Yale University Press, 450pp, £30.00

ISBN 9780300144857

Published 28 April 2009

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?