Urgent need to confront land subsidence following major earthquakes

A new study warns that the next major earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which stretches from Washington to northern California on the western coast of the USA, could dramatically increase coastal flood risks by causing the land to sink, explains one of the researchers, Benjamin Horton, Dean of the School of Energy and Environment at City University of Hong Kong.

Sponsored by

Sponsored by

HONG KONG (6 May 2025) —While most coastal flood hazard analyses usually focus on rising sea levels due to climate change, a growing body of research shows that another grave factor is often overlooked: land subsidence triggered by colossal earthquakes, explains one of the researchers, Benjamin Horton, Dean of the School of Energy and Environment at City University of Hong Kong.

“Our study underscores the need to consider combined earthquake and climate impacts in planning for coastal resilience at the Cascadia subduction zone and globally,” he added.

Earthquake-induced land drop

According to findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in April, a long-anticipated regional earthquake could suddenly cause the ground to collapse by up to two meters across parts of the Pacific Northwest.

“This abrupt sinking would immediately raise sea level and expand coastal floodplains far beyond their current boundaries,” explains co-researcher and lead author Tina Dura of the Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech.

Deploying advanced earthquake modelling and geospatial analysis, Dura explains that the number of people, homes, and roads exposed to coastal flooding could double if a devastating earthquake struck today.

Their study also revealed that the impact of earthquake subsidence could more than triple the region’s flood exposure by 2100 when combined with projected sea-level rise from climate change.

Horton says the world needs to note that climate-driven sea-level rise is increasing the frequency of coastal flooding worldwide, and sudden land subsidence associated with great earthquakes will make the coastal flooding much worse.

A massive earthquake in the Cascadia subduction zone could cause up to 2 metres of sudden subsidence, dramatically raising sea levels and significantly increasing the flood risk to local communities, Horton warns.

Support for policymakers

The historical record shows that coastal subsidence caused by massive earthquakes can have overwhelming, long-term impacts, highlighting the severe risks of earthquake-induced land loss and the urgent need for resilient planning.

Cascadia earthquakes are expected every 300 to 500 years, with the last 9.0 earthquake hitting the region 324 years ago.

More recently, earthquakes in Chile in 1960, Alaska in 1964 and the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake in 2004 caused vast amounts of damage after the land subsided.

In addition to the tsunami, Japan’s 2011 Tohoku earthquake caused a land subsidence of around 1 metre, damaging ports, eroding shorelines, and altering river mouths.

“Our study highlights an urgent need for coastal planners globally to account not just for rising oceans, but also for the earthquake threat beneath the Pacific Northwest,” Horton continued.

“We hope our findings can support policymakers, especially those in coastal communities in this region, as they prepare for compound hazards from earthquakes and climate-driven sea-level rises, and provide critical insights for tectonically active coastlines globally,” he added.

Benjamin Horton is pictured in 2023 at the Antarctic Peninsula, where he was studying the major source of climate-driven sea-level rise: melting ice sheets.

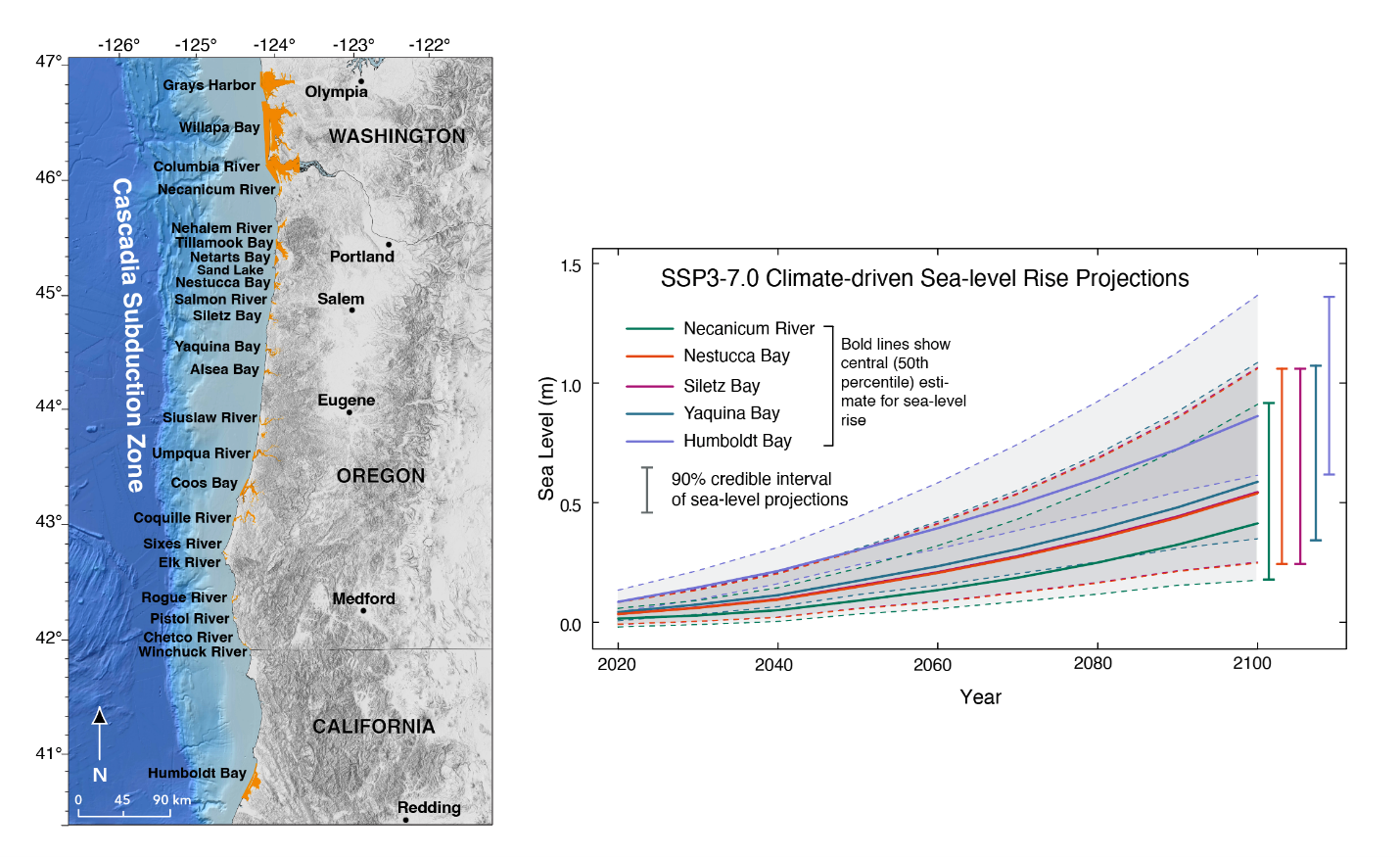

The image on the left indicates the location of the Cascadia Subduction Zone; the image on the right reveals projected sea-level rises in this region.

Benjamin Horton (back row, third from left) and Tina Dura (back row, centre) are pictured doing field work with other members of the research team in the Cascadia region.