Last month, the Special Inspectorate General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) issued its final report on the US’ two-decade long, $148 billion effort to reconstruct Afghanistan following the removal of the Taliban from power in 2001.

The report’s conclusion is stark: “the US experience in Afghanistan demonstrates the need for sober assessment of what is genuinely achievable and what, conversely, may be beyond the reach of external intervention.”

Apart from the pursuit of Osama bin Laden in the wake of the 9/11 attack, a significant element of the publicly stated rationale in the West for the invasion of Afghanistan was to promote women’s rights and equality – not least in education.

Human rights reports detailing the Taliban’s widespread violations of women’s rights were widely quoted as part of the justification for the October 2001 invasion, while a US State Department report on “the Taliban’s war against women” published the following month – by which time the group had largely lost control of the country – declared that Taliban rule had “cruelly reduced women and girls to poverty, worsened their health, and deprived them of their right to an education”, noting that “since 1998, girls over the age of eight have been prohibited from attending school”.

Earlier in November, US president George W. Bush told a conference on combating terrorism that, in Afghanistan, “women are imprisoned in their homes, and are denied access to basic health care and education.” Days later, his wife, Laura, declared in a radio address that the fight against terrorism was “also a fight for the rights and dignity of women”. And the UK prime minister Tony Blair’s wife, Cherie, called for post-conflict development work to be focused on “giv[ing] back a voice” to Afghan women.

Success in that regard, however, was always patchy. The $252 million that the US alone spent in this area was meant to “ensure a better future for Afghan women and their families by supporting legal rights, improving access to public services and jobs, and encouraging inclusion in public life”. But programmes, the SIGAR report found, were “fragmented, not well coordinated, [and] were not sustainable”. And since the Western withdrawal in 2021 and the Taliban’s swift return to power, “many reforms and rights achieved through U.S. efforts have been rolled back”.

Similarly, efforts costing $1.7 billion to improve “basic and higher education, literacy, and skills training” were “uncoordinated and did not expand access to education as intended”. Student enrolment increased, but “that progress was rolled back when the Taliban seized control in 2021, causing educational access and quality in Afghanistan to further deteriorate, especially for girls and women.”

That is quite an understatement. While the Taliban reassumed power initially insisting they would respect women’s rights, they quickly moved to segregate university classrooms by gender, and then to banish women from them entirely. Girls are also banned from attending school, and women are barred from most workplaces, including NGOs, government offices and private businesses, except in narrowly segregated settings such as women’s healthcare. Women are even banned from public parks.

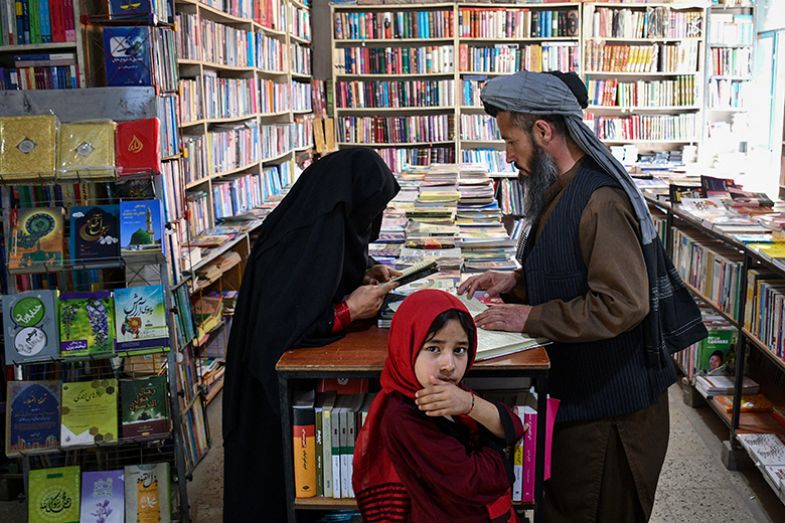

Since the US money supply was cut off by the closure of USAID last year, the Taliban’s oppression of women has only got worse – even as the country continues to receive aid from other international donors. In September, for instance, the government issued an official letter to all schools and universities – public and private – ordering the removal of all books written by female authors. This move follows earlier orders for radio and television stations to eliminate female voices from their broadcasts.

These policies are part of the broader campaign to erase women from the whole of public life. Now it is targeting their intellectual legacy, erasing them from the nation’s academic and intellectual memory. With each successive order, the regime tightens its grip, devastating not only women inside Afghanistan but also Afghans abroad, who fear for the safety and mental well-being of loved ones still in the country.

The ministries of education and higher education have blacklisted hundreds of titles across literature, sciences and social sciences, mandating their removal from libraries at every level of education. They justify this by claiming the texts violate Sharia – a radical misinterpretation of Islamic law that ignores the well-documented role women have played in knowledge production throughout Islamic history.

The banned books represent a vital source of knowledge in a country with already limited literature in all disciplines. Among them are books on Pashto grammar authored by a leading female linguist, whose father is a celebrated figure in Pashto literature. A grammar book cannot contravene Islamic principles: it deals with language structure, not theology. The only “problem” with this one is the gender of its author.

University administrators have been given strict deadlines to comply, and books have already been removed from library shelves in major cities, including Kabul, Herat and, especially, Kandahar, the home of the Taliban’s supreme leader, Mullah Hibatullah.

Female authors themselves are, of course, heartbroken. One poet now living in the US said: “This regime banned my book, which is only poetry – my feelings, my sorrows. What in my poems is against Islam? Show me, and I will discard it myself. If not, then my book is banned only because I am a woman. This hurts as if someone took my child.”

A former professor at Kabul University posted on social media: “This means half of our intellectual knowledge is being erased. Among these are great authors and great books. Students are unfortunate to have these vital sources of knowledge forcefully taken away.”

The ban severely impacts students at all levels. Younger students’ worldviews are being shaped by this censorship; one schoolteacher recounted his inability to counter a pupil’s suspicion that “there might be content against Islam” in women’s books, citing fears for his own safety. A university student lamented the loss of key reference texts, while another noted the irony of banning works by historical figures like Nazoo Ana and Zarghona Ana – poetesses and maternal figures in Afghanistan’s founding history.

This book ban follows the 2024 “morality law” from the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, which forbade women from speaking loudly in public – effectively muffling their voices in daily life. That law also forced media to stop broadcasting female voices, eliminating women news anchors, singers and even characters in foreign shows. The Taliban claimed that apart from containing female characters and voices, such shows – most of which come from Turkey or India – do not align with Afghan cultural values more broadly.

Women have also been banished from the radio, on which many rural Afghans still rely – not just as presenters but as any kind of contributor. For instance, certain radio stations run public-awareness programmes on Islamic topics, health and social/family issues, hosted by (male) doctors, Islamic scholars, social activists or educators. Listeners call in live with their questions, and the main audience for these programmes is women – particularly housewives in rural areas, most of whom have remained illiterate. Hence, women used to make up the majority of callers. Under the new rules, however, radio stations have been forced to stop accepting phone calls from female listeners altogether.

International expressions of outrage about the Taliban’s latest attack on women’s presence in Afghan society and culture have come thick and fast. The United Nations and NGOs such as Amnesty International condemned the book ban as a form of cultural genocide, for instance.

There have also been some efforts at resistance. For example, a group of female authors in exile have published six volumes of a digital magazine containing pieces by Afghan women, as well as translations. Female authors in exile promise to continue writing, and while the physical possession of the blacklisted books remains dangerous within Afghanistan, they are being shared digitally through WhatsApp and Telegram. The trouble is that even such digital forms of exchange are now being suppressed by the Taliban’s intensified nationwide internet blockade.

The blockade has also shattered online teaching and learning, which had become a critical alternative for Afghan students in general, and girls in particular. For instance, recent internet restrictions forced the shutdown of Kabul Online Medical Classes – the last hope for hundreds of Afghan girls pursuing higher education from within their own homes. Once hailed as a beacon of hope after the 2021 ban on girls attending physical classrooms, this virtual institution has now joined the growing graveyard of women’s aspirations under Taliban rule.

Kabul Online Medical Classes were launched by Afghan academics in exile, operating entirely on a volunteer basis. Leading professors in the field, who had fled Taliban restrictions to the US and EU, worked tirelessly to deliver the teaching despite the threats to their own mental health and long-term security from tightening Western immigration policies, leaving them with no guarantee of permanent safe haven.

One former professor at a leading Afghan public university, who is now a guest researcher at a US institution, posted on Facebook: “We received no salary and even placed ourselves under extra pressure to prepare teaching materials – kept going only by the satisfaction of keeping our sisters’ dreams alive.” Another former lecturer at a private Afghan university, who is now studying for a doctorate in Germany, told me that despite his PhD commitments, he often teaches at 4am or 5am local time to match morning hours in Afghanistan.

The students, all highly motivated young women, attended live sessions diligently despite their household duties, often using data paid for by the back-breaking labour of their fathers or brothers. “These girls were brilliant,” one professor recalled. “Many scored higher than students I teach at Western universities. Their hunger for knowledge was unmatched.”

For a time, this online university symbolised victory over oppression. In remote Badakhshan villages and cramped Kabul apartments, young women whispered introductions of each other as “future doctors of Afghanistan”.

But those dreams collapsed in October, when the Taliban’s Ministry of Telecommunications – under direct orders from Mullah Hibatullah – imposed sweeping new internet controls, including the blocking of high-speed data packages and the banning of virtual private networks (VPNs). As Afghanistan was severed from the connected world, live classes became impossible to conduct; even contacting family and friends was blocked. A PhD student in Germany posted: “This was a real catastrophe for me, my family, and my students...Everyone felt Afghanistan was drowning in an ocean of evil.”

I have previously proposed an internationally staffed Open University for Afghanistan. But although internet access has since been partially restored, the October outages signal that it can – and will – be blocked again, meaning that any online university could go offline within minutes. Afghan academics must therefore explore other alternatives.

International technology firms such as SpaceX (with its Starlink satellite internet) could assist by providing temporary internet connectivity in certain areas. But a lasting resolution requires the international community to stand behind Afghan scholars to push for policy change. At a minimum, financial pressure must be applied on the Taliban to take its foot off women’s throats.

SIGAR found that some of the millions of dollars that the US continued to direct to Afghanistan for humanitarian purposes post-2021 “benefited the Taliban”, and misappropriation of the international funding that continues to flow into Afghanistan to maintain food supplies and basic services remains a problem. The international community must find a way to prevent the Taliban from benefiting from international funding – while offering it financial incentives to reverse course on women’s rights.

The aid funding keeps many Afghans alive – but what kind of life are they living? That question is now an especially stark one for women and girls. The international community must recognise that sustaining access to education is not merely an act of mercy but a stand against oppression.

The regime’s actions are poisoning a generation of learners. Without decisive action to protect women’s education and cultural contribution, the dreams of an entire generation of Afghan women may be extinguished. And all the hundreds of billions of pounds that have been spent on Afghanistan really will have been completely wasted.

The author is based in Afghanistan and has requested anonymity for safety reasons.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?