Sue Law meets a sculptor who mucks about in car parks to show industrial design students how curves in cars matter.

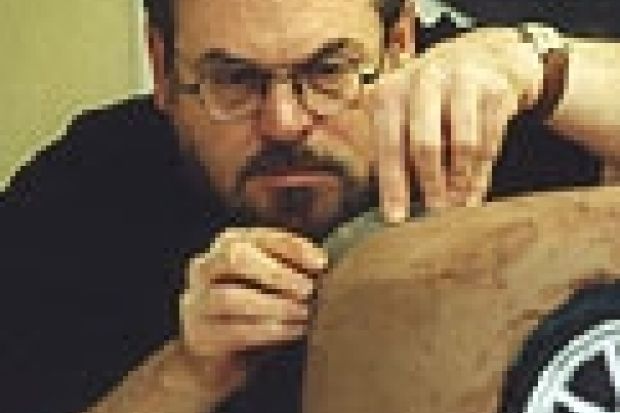

John Owen has a distinctly hands-on approach to teaching. A sculptor who trained at the Royal College of Art, he combines the artistic with the practical in his industrial design lessons at Coventry University.

His students use the latest computer-aided design, but he says nothing can replace the learning experience of getting to grips with the real thing.

He uses clay modelling and close analysis of vehicles to give students an understanding of form, which proves invaluable in the workplace. Many graduates now work as designers for car-makers, including Lotus and Mercedes-Benz.

A dozen final-year students from the BA and MDes in transport design arrive in the lofty clay-modelling studio for a workshop. They are about to tackle a project designing and building their own vehicle and are eager to pick up any tips.

"OK, let's have a look at this model. Do you think he has handled that well?" Owen asks, as the group gathers round a clay model of a futuristic sports car, crouching to check the line from different perspectives. They discuss the curves of the side panels, before moving on to a second car. "Horrible," pronounces Owen. "You can see it is too stubby. What would you change?" "Everything," the group choruses, laughing. They discuss the proportion of screen to bonnet and the length of the vehicle.

"The transition from 2D to 3D is what sorts out the sheep from the goats. It is very hard to go from a sketch to the model," Owen says, moving to a half-finished model surrounded by shavings of clay.

He shows the group how to use a range of tools on the clay, marking out a curve with a length of fishing-line, then scraping and smoothing the surface. The group watches in silent concentration, occasionally throwing in a question on technique, as Owen works along each curve, finely honing the car's side.

"How do you get the model symmetrical?" Owen asks. He demonstrates a simple method using a paper template. "You need a lot of patience, but trust your fingers - have a go. You will be surprised at how accurate you are," he assures them.

Next he explains that the students need to analyse some real vehicles before starting on their own sketches. As the group files out and walks to a nearby car park, Carl, one of the undergraduates, says how much he enjoys the clay modelling lessons. "He is very precise, but never negative even if your model is not right," he says of Owen's teaching style.

Owen strides into the car park, wielding the long bendy stick he uses to demonstrate curvature. Traffic thunders overhead on the bypass as the students huddle shivering round one of the cars.

But the freezing weather does not dampen their enthusiasm. They crouch down to look closely at the wheel arch, as Owen explains two common misconceptions - that all wheel arches are semicircular and that all car sides are flat.

"Now look at those two four-wheel drives over there. If that triangular-shaped one was a few inches higher it would look like Toblerone chocolate. I would put more curve on the sides; it would look far better," Owen says of a bright yellow Jeep.

A new blue VW parked nearby also comes in for criticism: "I don't like this, it is too fat. From a distance the softness dominates, although you can see close up that the form is quite strong."

As the car-park tour ends, the students talk over the morning's session: they agree that teaching a multidimensional subject is difficult.

"It is a 3D course so it should be taught in a 3D way. That is more important than traditional lectures," one student says.

In the studio, Owen explains that he originally planned to be a professional artist, but did not like the "schmoozing in private galleries" that was necessary to sell his work. "The 3D form is what interests me but finding a language to talk about it is very difficult. I teach in an exploratory, freestyle way. My lessons are unplanned and I like the interaction. It is more consultation than teaching as learning objectives can change minute by minute. It may look like chaos, but it isn't."

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?