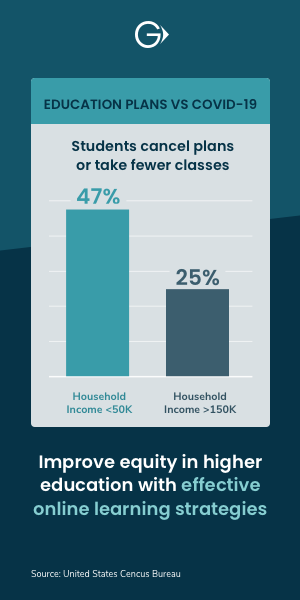

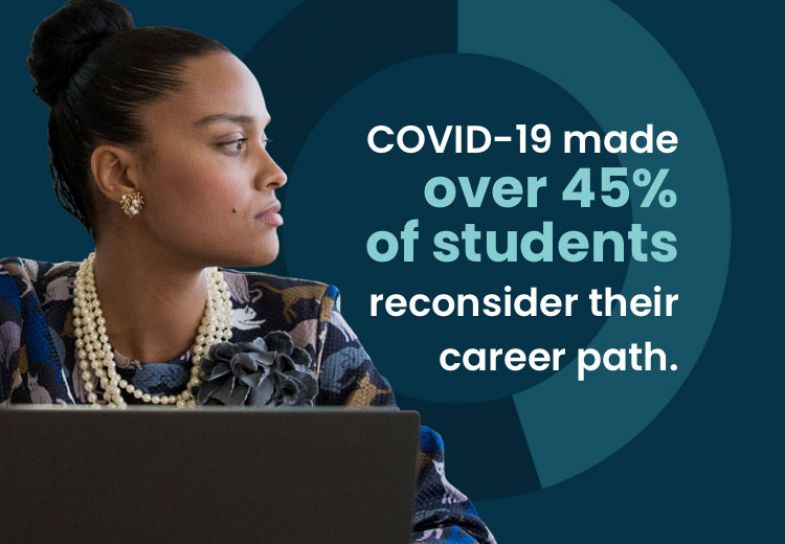

The pandemic forced many hybrid and in-person programs online, some for the first time. As the demand for online learning options continues to grow, it is time to transition from emergency virtual education to sustainable online learning solutions. As institutions work to achieve this, keeping the needs of working adult students at the forefront is critical to long term strategy.

According to Guild Education, 155 million Americans lack a postsecondary degree or meaningful credential, and 88 million are in need of formal upskilling or reskilling. Innovative Fortune 500 employers ignited a trend of underwriting the cost for employees to pursue degrees and credentials through education benefits. Today, an estimated 92 per cent of employers now offer education benefits, most commonly in the form of tuition support. As a result, working adults are rapidly becoming the new traditional students. (Conversely, degree program enrollment of 18-24 year olds is expected to decline by 12 per cent over the next decade in the US alone.)

Working adult learners have unique needs that often fall outside of the purview of their traditional counterparts. Roughly half of working adult students are parents. Many have caregiving responsibilities, shifting work schedules, and added time constraints that many students don’t typically have. These unique needs should be taken into account when leveraging insights from the last year to improve outcomes for students learning online.

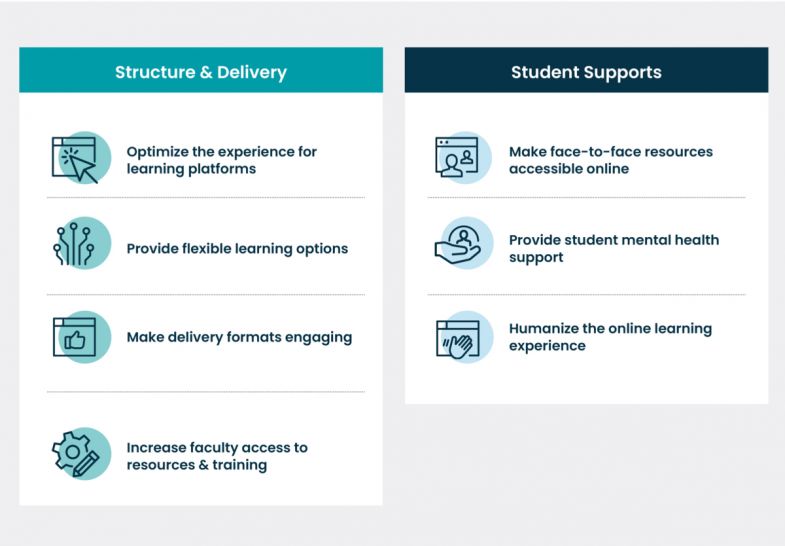

Broadly, improvements can be divided into two major categories, structure and delivery, and student supports. Below is an overview of recommended areas of focus for each.

Structure and Delivery

What works face-to-face does not necessarily work online. Rethinking design and delivery to optimise student experiences can drastically improve student outcomes.

- Optimise the experience for learning platforms: As of November, 2020, 49 per cent of faculty that transitioned to online teaching report that they still use the same course instructional materials as they did for in-person learning. Reverse-engineering lessons to outcomes as in Wiggins and McTighe’s backwards-design model forces a consideration of the competencies students are expected to demonstrate, as well as the best ways to make the online learning experience active to ensure lessons have staying power.

- Provide flexible learning options: Not every student has reliable internet access or more than one computer. For working adults students that may have to share technology with children who are learning online and juggle work schedules, consistent synchronous learning may not be possible. Providing a range of synchronous and asynchronous options can enable students to continue to pursue a degree without interruption, and carries inclusion implications for students who learn differently.

- Make delivery formats engaging: According to Guild education survey data, 15% of working adult students report difficulty with format as their top challenge in persisting. Deploying attention renewal strategies (such as sharing high-level structure and goals of each lesson) in tandem with active learning strategies (such as performance-based assessments) fosters better engagement and persistence. Taking a holistic approach to assessment and evaluation of the student learning experience can create a cycle of improved outcomes. Guild explores these concepts in detail here.

- Increase faculty access to resources and training: Just as students are not automatically ready to learn online, faculty are not automatically prepared to teach online. Pairing experienced faculty or instructional design experts with professors new to teaching online can alleviate pressure on faculty and improve the learning experience.

Student Supports

Successful online learning means students can access the same resources and support online as in person. The end of the pandemic does not mean an end to the student mental health crisis; shoring up support and ensuring a sense of community for online students are necessary components of sustainable online learning experiences for students.

- Make face-to-face resources accessible online: Similar to offering synchronous and asynchronous learning options, these resources should be accessible in a variety of ways. Working adult students represent a broad spectrum of backgrounds and skill sets, and though online learning may be preferable for many of these students, not all will be prepared for learning online. Additional resources, such as introductory courses to prepare students for online learning, manage time, and connect with other learners, will be foundational to student success.

- Provide student mental health support: The student mental health crisis began before the pandemic, and it will continue beyond it. Offering versatile resources to online students is critical, as is centralising these services through a single online hub. Alignment in communications across the institution normalizes the conversation around mental health and helps ensure students know where to go for support.

- Humanize the online learning experience: Students who participate in online conversations are 25 per cent more likely to graduate. Taking steps to give students opportunities to work in groups, connect outside of the virtual classroom and develop a sense of belonging, is a central component to persistence and success.

Online learning is here to stay. Leveraging insights gained from the challenges highlighted by the pandemic can become a pathway to transforming online learning from an emergency option to a sustainable, outcomes-focused strategy.

To learn more, download Guild Education’s white paper, Transforming Emergency Virtual Education Solutions into Effective Online Learning.