New Galleries of Ancient Egypt and Nubia

Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology

Opening on 26 November

Framed by the Doric columns of the Ruskin Gallery, a colossal statue of the Egyptian god Min grasps the base of its erection and holds it at half-mast, presumably pleased to have the stone member back in place after a century of separation.

This week, the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford opens a suite of renovated galleries devoted to its world-renowned collection of Egyptian antiquities. The restoration of the ancient phallus on the statue of Min - one of a pair displayed here, with a third in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo - is just one of the remarkable changes undertaken at lightning speed over the past year, supported by £5 million of charitable funding led by the Linbury Trust. The new galleries of ancient Egypt and Nubia (northern Sudan) complete the Ashmolean's ground floor, which is dedicated to the ancient world. They continue the theme of "Crossing cultures, crossing time" embedded in the museum's 2009 transformation, which more than doubled its exhibition space by replacing a hotchpotch of rooms tacked on to the 1845 building with one vast extension by architect Rick Mather.

Mather is also responsible for the six Egyptian galleries, which have been created by reconfiguring the Ashmolean's existing footprint and incorporating the Ruskin Gallery, part of Charles Cockerell's original edifice. Named after John Ruskin, Oxford's first Slade professor of fine art, the gallery was home to the museum shop until last year. In the Neo-Classical grandeur of the space, a plaster cast of the Parthenon Frieze circles the walls over the Min statues, as if it can't quite keep pace with what's happening below.

The Ruskin Gallery is the starting point for a route that encourages visitors to circulate clockwise around the new exhibits. The layout is chronological without being pedantic. Each gallery is themed to play to the strengths of the collection while drawing on new research and ways of thinking about ancient Egyptian society. The Min statues are a case in point: the theme of this gallery is "Egypt at its Origins", which presents a wealth of material leading up to the period of state formation in the Nile Valley (around 3000BC), including the earliest evidence for kingship and writing. Oversized mace heads and cosmetic palettes are intricately carved with animal imagery and depictions of the first pharaohs, while new, high-tech display cases make it possible to display the rare and delicate carvings known as the "Hierakonpolis ivories" (named after the site where they were excavated in 1898-99). Figures of various humans, animals and boats, some of which may be furniture parts, hint at a vivid array of imagery in the service of royal and divine power. The ivories were found buried in a deep pit inside a temple, with centuries' worth of similarly decommissioned objects, some of which are also on display.

These early works may not match visitors' assumptions about what "ancient Egypt" looks like, but that is the point. The essentialist idea of Egypt enshrined in popular culture is a fantasy. Reality - or rather, the materiality of the archaeological record - is much more strange and interesting.

Another less familiar view of ancient Egypt greets visitors entering the next gallery, which Mather has opened up to create views into adjacent rooms. Named after Francis Llewellyn Griffith, first holder of the university's chair in Egyptology, this gallery houses the one fixed point in the renovation programme: the sandstone shrine of King Taharqa, which sits on a reinforced floor to support its weight. Dating from around 680BC, the shrine is a one-room structure built to fit amid the massive columns of the Temple of Amun at Kawa, located between the third and fourth Nile cataracts in what is now Sudan. Taharqa's dynasty considered this stretch of the Nile home but ruled the whole valley for 100 years, defying simplistic assumptions that might be made today about borders and identities.

After Griffith worked at Kawa in the early 1930s, the shrine was dismantled and shipped to Oxford in some 150 crates. In the redesigned gallery, circles outlined on the floor indicate where the shrine abutted the temple columns, while daylight bulbs behind the glass brick ceiling (a 1950s survivor, previously painted black) accentuate the reliefs.

What is missing, here and elsewhere, is an upfront statement about modern as well as ancient politics. After all, Griffith was working in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, an outpost of Empire that sought to divide Egypt from Sudan, and Sudan within itself. It was a strategy with ramifications still felt today (South Sudan achieved independence earlier this year), as is the legacy of the "veiled protectorate" of Egypt, under which museums such as the Ashmolean benefited from the division of archaeological finds. Objects cross more than just cultures and times - they cross imbalances of power, too.

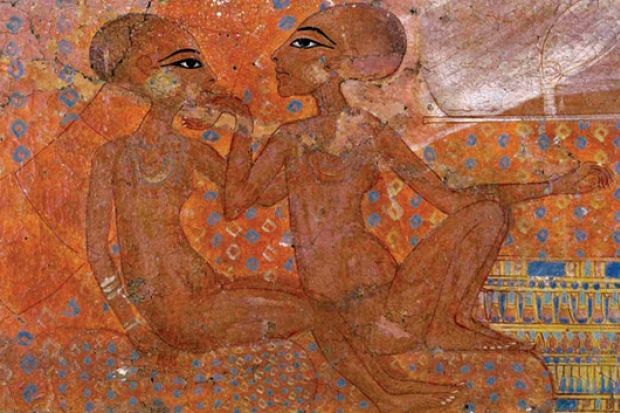

The history of Egyptology at Oxford and of the Ashmolean's Egyptian collection is a distinguished one, however, and the new galleries highlight the achievements of individuals including Griffith; artist and copyist Nina Davies, whose paintings drench whole walls in colour; and Sir Alan Gardiner, a scholar who also donated a number of the objects on display. If a university is a community based on research and reflection, then university museums play a vital part not only within that community, but also within wider society. Increasingly, it falls to these museums to act as the public face of research activities, especially in the arts and humanities, but with a minimum of public funding or recognition.

Balancing the needs of family visitors, school groups, tourists and academic users can be a problem to which there is no perfect solution, but the calibre of the Ashmolean displays makes a start by lavishing the best in conservation care, well-thought-out design and academic research on the 40,000-strong objects in the Egyptian collection. One result is that the galleries include a number of objects on display for the first time in decades, if ever, from Min's missing member to painted portraits from Roman-period mummies, restored from wooden fragments.

Collaborations with other museums have also added to the displays: spotlit inside the Kawa shrine is a dark stone statue of Taharqa himself, on loan from Southampton City Council; and in a gallery devoted to the city of Amarna, where Tutankhamen might have spent his childhood, the Ashmolean's statue of King Akhenaten stands side-by-side with a statue of Queen Nefertiti lent by the British Museum. Both statues were found in pieces in the garden of an ancient house, evidence of the occupants' dedication to royalty - not as fashion icons, but as earthly links to the divine.

The last leg of the circuit returns visitors to the Randolph Gallery, where classical marbles line the walls. Ruled by Greek kings and Roman emperors, Egypt remained a society of many facets and many faces, some of which, like the mummy portraits, may seem deceptively familiar, while others, sheathed in gilded plaster masks, appear more alien and "exotic". But portraits and masks alike belong to mummies wrapped in intricately folded bandages, for this was a period when the residents of Egypt adapted cultural practices to suit a new world order.

In this final section, the mummy of a two-year-old boy lies next to artist Angela Palmer's sculpture based on its computed tomography scan, comprising a row of glass panes within which the image of the body changes depending on where the viewer stands. It is a timely reminder that, like the stark differences that seem to divide East and West today, ancient Egypt is in many ways of our own making.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?