Gauguin: Maker of Myth

Tate Modern, London

30 September 2010-16 January 2011

National Gallery of Art, Washington

February-5 June 2011

Gauguin: Maker of Myth

Edited by Belinda Thomson

Tate Publishing, 256pp, £35.00 and £24.99

ISBN 9781854378712 and 9023

Painters, like politicians, have their mythic arcs. If in the latter case the archetypical arc is log cabin to White House, then Gauguin's mythic arc might be described as white house to log cabin.

Born in Paris, raised for a few exilic years in Peru, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) was first of all a "coarse sailor", as he put it, in the Merchant Marine and the French Navy - a Conradian youth - and then, of all things, a stockbroker. As a painter he was a late starter and a fast learner. He found a mentor in Camille Pissarro - the best in the business - and an exemplar in Paul Cézanne, whose groundbreaking work he collected, and copied, with a kind of aristocratic assumption that this was what he was born to do. Gauguin had chutzpah. Gauguin thought Gauguin a great artist.

His preferred self-image was the wolf in Jean de la Fontaine's fable "The Wolf and the Dog". The lean wolf envies the sleek dog, who feeds on the titbits from his master's table. The dog urges the wolf to give up the life of the wild in favour of comfortable domesticity. The wolf is tempted, until he spies the dog's neck, bald from a snug collar.

"'Then you're not free? You can't go where you choose? Run where you will?...Keep your fine feasts! I'll keep my liberty!' Whereat our wolf went running off. He's running still."

Gauguin ran for a while with the Impressionists, but running with the pack did not suit him. Progressively he threw over the traces of Parisian life, family life, bourgeois life. Even still life could not contain him, though he continued to bank on Cézanne's apples and pears. During the 1880s he ranged further and further afield in search of what he called the "wild and the primitive", cheap living and "virgin nature" - his own heart of darkness. This took him to Pont-Aven in Brittany, to Martinique, and to Arles and the disastrous cohabitation with Vincent Van Gogh in the "Studio of the South". Gauguin fled and Van Gogh severed his own ear.

Back in Paris, Gauguin transferred his affections to the Symbolists, meeting and charming the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, among others. When he wished, Gauguin oozed charm. He had decided on a truly tropical adventure. After considering and rejecting Tonkin and Madagascar, he chose Tahiti. Such a venture required funds. This called for a publicity campaign, a sale of works (which raised some 10,000 francs) and a grant application - a request for government sponsorship "to study and paint the customs and landscapes". The application was successful. In 1891, he set sail for Tahiti and immortality.

In the event, it was immortality postponed. Gauguin returned to Paris two years later, after an intensely creative period, almost penniless, expecting a hero's welcome. His impregnable self-belief was soon underpinned by the response of the critics to an exhibition of his Tahitian works. Early in 1895 he was diagnosed with syphilis. Later that year he sailed again for Tahiti, never to return. He died of syphilitic heart failure in 1903.

At an auction of his effects, a young French naval doctor, ethnographer and writer, Victor Segalen, succeeded in purchasing seven of the 10 canvases included in the sale, together with a large number of prints, photographs, drawings, books, sketchbooks and carvings (including the panels surrounding the door of Gauguin's "House of Pleasure"). By this self-proclaimed "act of piety", Segalen salvaged for posterity a treasure trove of material - much of which can be seen in the exhibition at Tate Modern - and in effect began the process of rescuing or reconstructing the artist's posthumous reputation. In the making and the mythologising of Gauguin, Segalen is seminal: one of the great strengths of the exhibition is exploring that connection.

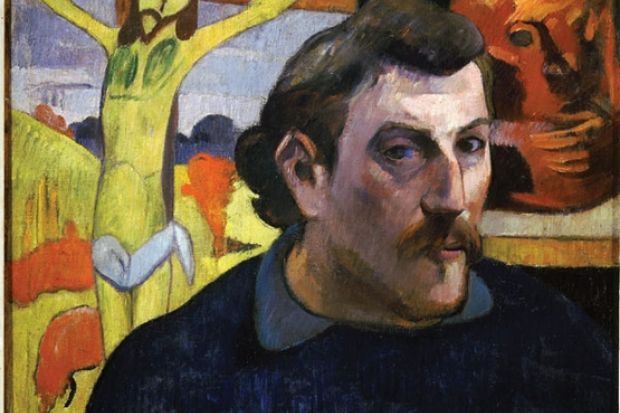

When it comes to myth-making, however, the central figure is Gauguin himself. Even among the tribe of self-portraitists, "PGo" (his signature-obscenity) was an exceedingly self-conscious character, at once calculating and outrageous. The first room of the exhibition is devoted to his self-portraits - a coup for the organisers - and is in many ways the strongest in the show. This gaggle of Gauguins is further augmented by others, semi-disguised, as perhaps in the Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel) (1888), or even The Yellow Christ (1889) - with Gauguin, anything is possible - and two masterly works not in the exhibition but reproduced in the catalogue, Self-Portrait near Golgotha (1896) and Self-Portrait Drawing (c.1902-03).

Gauguin's self-presentation was various. The lone wolf was joined by the dandy, who distributed photographs of himself to would-be admirers. A selection of photographs can be seen in the fascinating documentary displays that punctuate the exhibition; they betray something of his wolfish sizzle and sardonic hauteur. The same qualities are evident in his writing.

Gauguin had a distinctive voice. "This is not a book," begins his Intimate Journals. "A book, even a bad book, is a serious affair...If I tell you that, on my mother's side, I descend from a Borgia of Aragon, Viceroy of Peru, you will say it is not true and that I am giving myself airs. But if I tell you that this family is a family of scavengers, you will despise me." He was good at playing on or playing up his own life story. According to his most sympathetic dealer, Theo Van Gogh (brother of Vincent), "it's evident that Gauguin, who is half Inca, half European, superstitious like the former and advanced in ideas like certain of the latter, can't work every day in the same way." Gauguin himself wrote to his wife ("a wife incapable of living in poverty"): "You must remember that I have a dual nature, the Indian and the civilised man. The latter has disappeared (since my departure), which permits the former to take the lead...the sensitive man has disappeared, which permits the Indian to forge resolutely ahead." Acutely, the organisers remark on his carefully crafted savage nature.

The master concept of the exhibition takes its cue from this insistent self-fashioning. The focus is on unravelling Gauguin's "narrative strategies": the narratives or stories embedded in the works themselves - the parables of the paintings - but also the tall tales of his life. Unsurprisingly, that means a concentration on the artist-tourist and the immoralist; or to put it in the language of the catalogue, "otherness", "orientalism", "exoticism" and "cross-cultural exchange". In consequence, the exhibition is end-loaded, or Tahiti-heavy. Gauguin becoming Gauguin is a little truncated here. It may be that this is only to be expected: Gauguin would not be Gauguin without Tahiti. It was in every sense his ultimate destination; a century later, it seals his claim on our attention.

The virtue of this show is that it enables us to examine the force of that claim, confronted with work in every conceivable medium, including some intriguing wood carvings and ceramics. Was Gauguin, viceroy and scavenger, the great artist he believed himself to be? Perhaps he did give himself airs. Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897), a canvas of 1.39m x 3.74m, measured the ambition or inflation of his late work. Cézanne, the greatest painter of the age, who toiled for 10 years on the Large Bathers, would never have thought of such a thing. At almost exactly the same time, Conrad produced a slim novella of hallucinatory power called Heart of Darkness. Bonjour, Monsieur Gauguin!

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?