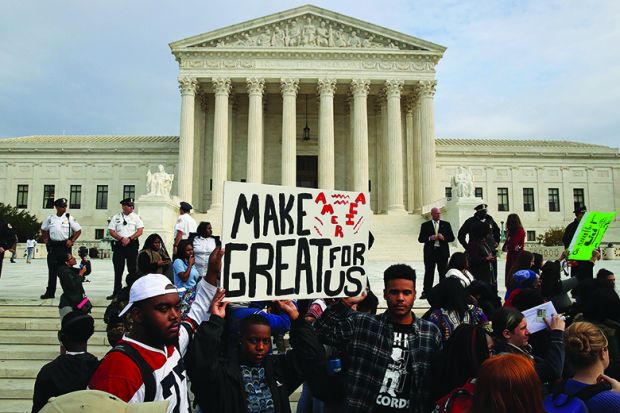

Lawmakers in half of US states are pursuing measures to restrict college-level teaching about race and other sensitive subject areas, and institutions appear unsure how to confront the issue.

The crackdown began last year largely at primary and secondary school levels but has shifted in recent months to the post-secondary sector, with lawmakers proposing college curriculum restrictions in at least 25 states and already having won approval in three.

Legislators across the nation are building on each other’s work and finding increasingly creative and bold ways to outlaw classroom discussions about racial and gender equity, said Jonathan Friedman, the director of free expression and education at PEN America, a writers’ organisation that has been tracking the phenomenon.

“These bills are moving from bigger, broader ideas to really specific, targeted forms of censorship against how people would talk about any kinds of issues in higher ed,” Dr Friedman said.

THE Campus resource: Talking taboos – how to discuss difficult subjects in class

The partisan pressure on the legislative front is accompanying and bolstering higher-profile acts aimed at the levers of institutional leadership and at prominent scholars. Those instances include the blocking and ousting of outspoken academics at the University of North Carolina, moves in Florida to restrict faculty from testifying in court against voter suppression efforts and to constrain presidential searches, and the imminent installation in Georgia of an outspoken Donald Trump ally as the head of the state’s university system.

National higher education leaders have voiced some protest against the developments but have largely left individual institutions to fight back as best they can, creating what Dr Friedman and other experts see as a rapidly normalising atmosphere of ideological attacks on basic academic freedoms.

The chief US higher education lobby group, the American Council on Education (ACE), has called on political leaders to stop interfering with classroom content.

“Higher education always functions best – that is, it provides the most value to the public – when campus officials have the freedom and flexibility to decide who teaches what to whom,” said Terry Hartle, ACE’s senior vice-president of government relations and public affairs.

ACE, however, declined to discuss any plans that US university leaders have for fighting back, noting that the acts of legislative interference in curricula are most common at the state level and infrequently affect college communities. “Most of these have been aimed at elementary and secondary schools,” Dr Hartle said.

Academics appear to be more concerned about the situation, if no more sure how to address it. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) has been producing a running stream of statements condemning legal restrictions at the state level and instances where public universities go along with them – sometimes forced by politically appointed governing boards or by the threat of reduced state funding.

Too many US political leaders, said the AAUP’s current president, Irene Mulvey, a professor of mathematics at Fairfield University, are “fighting against what those of us in higher education think higher education is for”.

Beyond the heavily spotlighted cases in North Carolina, Florida and Georgia, additional examples include Boise State University in Idaho, which cancelled diversity-themed ethics courses because a single white student complained, and Iowa State University, which told its faculty to be cautious about what they presented to their students after the state enacted a law forbidding the teaching of “divisive concepts” related to racism and sexism.

Iowa, Idaho and Oklahoma are the three states that PEN America counts as having already passed teaching content restrictions at the higher education level.

Dr Friedman acknowledged ACE’s recognition that most acts of legislative interference are aimed at school instruction. But, he continued, US higher education leaders were making a huge mistake if they did not see how those behaviours would eventually affect them and their students or if they failed to see how quickly state lawmakers were moving to directly apply those same restrictions across the post-secondary arena.

“The most alarming thing is the fluidity and the creativity” of partisan state lawmakers, Dr Friedman said. “It’s almost like a loosening of the legacy and traditions surrounding how state legislators historically left universities to govern themselves on matters of academic freedom, rather than try and police them,” he said.

Dr Friedman went on to say that US colleges and universities stood to be tragically surprised if they believed that such things could not start happening suddenly at the federal level, with control of Congress and the White House perpetually hanging in the balance and with a long-term 6-3 conservative majority on the US Supreme Court.

A major example, he said, is Texas, the second-largest US state by population. There, the faculty council at the University of Texas at Austin recently passed a resolution affirming the right of instructors to teach students about racial justice. In response, the state’s lieutenant governor, Dan Patrick, promised to use his role as president of the state Senate to end tenure for all new hires at Texas public colleges and universities, and to revoke it for those who do teach about the nation’s long-standing structural racial inequities.

“Universities across Texas are being taken over by tenured, leftist professors, and it is high time that more oversight is provided,” Mr Patrick said.

It’s a sign, Dr Friedman said, of how unprepared US higher education appears to be for the magnitude of what it is facing. “I think there’s a swagger that has spread among these state legislators that university leaders are not really ready to counter,” he said.

The AAUP expressed hope that academic institutions would face natural consequences from actions such as the selection of Sonny Perdue – a former governor with no higher education experience and a record of having discounted scientific evidence while he led the US Department of Agriculture in the Trump administration – to head the University System of Georgia.

Partisan appointments and curricular restrictions, the AAUP noted in one of its statements, are already attracting negative attention from students and from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), the accrediting agency that affirms Georgia’s state institutions as eligible for federal student aid.

“Appointing an inexperienced chancellor after a closed search will only exacerbate the concerns and will almost certainly have a negative impact on recruitment and retention of faculty and students,” the AAUP said.

Yet after initially warning Georgia officials that Mr Perdue’s appointment could jeopardise the system’s accreditation, SACS more recently told the AAUP that it would not protest against the decision, arguing that people lacking higher education experience have managed in the past to successfully lead colleges and universities.

Explaining that Georgia’s university system initially had no intention of interviewing anyone other than Mr Perdue, the head of SACS, Belle Wheelan, said she felt that SACS could not object once the system interviewed several other candidates.

“Folks don’t like his politics,” Dr Wheelan told Times Higher Education, in reference to Mr Perdue. “He makes no bones about his conservative beliefs, but we have no accreditation standards on that, and the only thing I can question is any non-compliance with our standards.”

It’s among a string of quick turnarounds in the realm of political interference in US education. The Trump administration made little headway in its threats to cut federal aid to universities that did not carve out protections for conservative thought on their campuses, only to have states begin exercising that power after it left office. Calls for bans on certain types of books largely began with complaints from some parents of elementary school children, Dr Friedman said, before they were embraced and rapidly amplified by partisan lawmakers.

And the initial partisan focus on blocking discussions of the nation’s extensive racial inequities has moved rapidly into other areas of conservative predilection, he said, mostly recently the calls in some states to forbid any LGBTQ-related materials in schools.

As with the main association of US university leaders, the leading association of US academic staff conceded that it saw limited options beyond continuing to speak out and hoping that national attitudes would change.

“It’s a very polarised time in the country right now, but I feel like the higher ed community is responding in important and meaningful ways,” said Professor Mulvey of the AAUP. But, she added, “We don’t have a magic wand.”

paul.basken@timeshighereducation.com

Gag orders: where the axe is falling on academic freedom

Data compiled by the writers’ organisation PEN America show widespread efforts to restrict the teaching of politically sensitive topics in US higher education. Three states – Idaho, Iowa and Oklahoma – already have enacted such legislation specifically aimed at higher education. The only one of those three that directly affects classroom instruction, according to PEN America, is Idaho, where teachers are forbidden to “direct or otherwise compel” students to agree with a list of concepts that lawmakers find “divisive”.

PEN America meanwhile counts at least 49 more bills pending in 25 states to restrict the teaching of politically sensitive topics in US higher education. They include:

New Hampshire HB 1313

Would extend to higher education an existing prohibition on schools that bars teaching that one race, gender or other protected class is advantaged over another, or inherently oppressive over members of another class, consciously or unconsciously.

Oklahoma SB 614

Would prohibit public universities from endorsing, promoting, demeaning or intentionally undermining any religious or non-religious faith, and forbid professors to “endorse, favour or promote socialism, communism or Marxism”, or to express or include any “anti-American bias” or “anti-American sentiment”.

South Carolina H 4605

Would ban conducting “instruction in any place of learning…in a manner that repeatedly distorts or misrepresents verifiable historical facts [or] omits relevant and important context” and would establish a tip line for members of the public to report violations to the state, with the threat of loss of state funding.

Tennessee SB 2290/HB 2670

Would ban public universities from including certain ideas related to race and sex in any “seminars, workshops, trainings, and orientations”, and require that campus diversity initiatives include promotion of intellectual diversity.

Wisconsin SB 409/AB 413

Would prohibit public universities from teaching about race or sex stereotyping, require course syllabuses to be posted on institution’s website, and ban requirements for employees to attend training promoting race or sex stereotyping.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: US universities face teaching restrictions

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login