The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson

Directed by Julien Temple

In selected cinemas from 17 July 2015

In early 2013, rock guitarist Wilko Johnson was diagnosed with apparently terminal pancreatic cancer. He accepted the diagnosis without demur – or a second opinion – and emerged from the consultant’s room with a transfigured, euphoric sense of the beauty of life. Refusing the offered chemotherapy as bringing too much pain for too little gain, he immediately set about enjoying to the full what he had been told would be his final year, making a series of farewell tours and guest appearances; recording a successful album with The Who vocalist Roger Daltrey, Going Back Home; and finding time to reflect on his newly found ecstatic response to the world around him in a series of interviews that form the backbone of Julien Temple’s intriguing new documentary.

The representation of Johnson’s positive acceptance of his prognosis, and what follows, is superbly realised by Temple. Johnson has always been a photogenic and engaging interviewee (as captured by Temple in Oil City Confidential, his 2009 film about the band Johnson co-founded, Dr Feelgood). This new film is not and was not intended as a straight biography, but we do learn much about Johnson’s education and family background, his non-musical interests – he provides enthusiastic reflections on history and astronomy – and his favourite places.

We gain comprehensive insight into the ways in which Johnson makes use of his accumulated knowledge in responding to his condition. While it is driven by the acceptance of a biological process, the expression of Johnson’s elation is not naturalised but cultural, and in representing this the film is a profound celebration of both Johnson’s and Temple’s culture. Like William Blake, Johnson can now clearly see the world in a grain of sand, and his constant references to the ecstatic works of Blake, Wordsworth, Milton and Shakespeare provide the cultural keystone of his interpretive grid. On impressive display here is the learned Englishness of the grammar school and university English literature curriculum, an almost-lost world whose utility Johnson demonstrates perfectly.

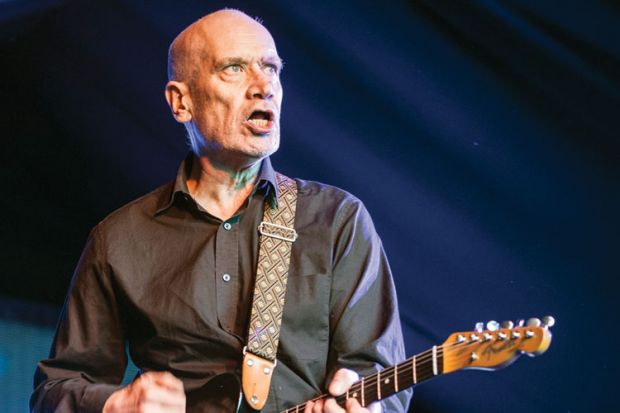

Then there is, of course, the music. We see a fair bit (but not enough) of Wilko Johnson the rocker, from the early days with Dr Feelgood through various later stages in his career up to and including some of the farewell shows. Staring into the middle distance and duck-walking around the stage, Johnson is the exemplary axe-man, his guitar constantly chopping and cutting – a style blurring the boundaries between rhythm and lead. These prime cuts of Anglo-American pub rock are complemented by soundtrack choices that demonstrate the film-maker’s art – Johnson’s ecstatic visions as seen through Temple’s camera are sonically underpinned by the historicised Englishness of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis and the spirituality (oddly appropriate, despite Johnson’s enthusiastically proclaimed atheism) of Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere.

Temple’s choices also include sampling from the work of other film-makers who have tried to deal with visions of ecstasy and death: Jean Cocteau, Luis Buñuel and Andrei Tarkovsky. Johnson’s reading of Hamlet’s soliloquy is intercut with scenes from an early 1960s television production starring Christopher Plummer as the Prince. The chess-game dialogue between Death and the Knight, in Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (1957), is glimpsed in a couple of extracts, and also lovingly parodied by Temple and Johnson (who plays both parts, his hooded Death reminding us of his occasional non-speaking role as the hangman Ser Ilyn Payne in the first two seasons of Game of Thrones).

The Johnson versus Johnson chess game, like most of the film’s interviews, takes place in Johnson’s (and Dr Feelgood’s) manor – the faded Essex holiday resort for East Londoners, Canvey Island. The island’s estuarial mud and concrete flood defences, its tiny houses and the industrial towers of the petrochemical plant are shot fairly straight for the most part, although they are juxtaposed against the flora and fauna of the “natural world” of countryside and ocean. These are often seen through processed filter and focus effects, giving the hallucinatory feel called for by the subject matter. Thus Temple tries to show us Johnson’s euphoric vision as he celebrates life while accepting his forthcoming death.

But in an astonishing turn in the final act of the film, hallucination is replaced by salvation. In early 2014, Johnson’s prognosis was changed by Charlie Chan, a hobbyist gig-photographer and surgeon who came to one of the farewell performances, looked at him and thought that the tumour was in fact treatable. Others agreed, and somewhat belatedly Johnson had his second opinion. There followed a day-long, successful operation to remove the tumour, his pancreas and various other internal organs. This leaves Johnson in a state of puzzled, and post-ecstatic, physical recovery, while the film – which had clearly been intended as a memorial celebration – must change gear to represent its subject’s new state of being.

From this moment, in the film’s coda, we enter a rather different world. For a while, the philosophical rocker is replaced as principal talking head by Emmanuel Huguet, the surgeon who led the life-saving operation. Shot looking down at the camera – which bestows massive authority, even a kind of divinity – the surgeon briefly and straightforwardly explains what went on at each stage. He thus renormalises Johnson. He is now the survivor, physically weak but growing stronger, at one point nervously demonstrating to us that he still has that guitar technique. The wise old man who had rejected chemotherapy and lived, for a year, blissfully in the moment has become the human subject of medicine’s increasing power to cheat death.

Cancer survival is the new normal. In the UK, approximately half of all those diagnosed with cancer live for at least a further decade. Survival rates have increased by 40 per cent over the past 40 years, and are continuing to rise (although many cancers remain comparatively lethal, and survival is often hedged about with continuing treatment that can have debilitating side-effects). As Iron Maiden vocalist Bruce Dickinson – another rocker who has recently had treatment for cancer – has pointed out, anyone who announces that they have had, and survived, treatment for a particular cancer soon discovers that they are not alone. While this sense of shared experience, and shared knowledge of treatments and survival strategies, is often expressed pseudonymously, through social media, it can also be achieved through cultural leaders such as Dickinson making their conditions public. This in turn can encourage others to seek treatment early, and thus increase their own chances of survival. To that extent, the film’s unintended coda offers an exemplary story.

Biography or not, music film or not (for what it’s worth, Temple claims it is neither), The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson allows us to see the world as a particular musician sees it. To that extent, it forms a telling contrast to the gloomy presentation of the star musician’s life and death in Asif Kapadia’s recent film Amy. The preternaturally talented young singer Amy Winehouse was helplessly caught in a ghastly parody of the rock life, surrounded by others whose selfishness and greed helped cause her untimely death – in plying her with drugs and drink, and fuelling the destructive attentions of the press, they even seemed to sign the Faustian pact on her behalf. Johnson, older, wiser and less encumbered by the paraphernalia of celebrity culture, makes his own choices. May he live to make many more.

Andrew Blake is a visiting professor in cultural studies at the University of Winchester, having worked there and at the University of East London after a brief career in music performance. His writings on music include The Land without Music: Music, Culture and Society in Twentieth-Century Britain (1997), Living through Pop (editor, 1999) and Popular Music: The Age of Multimedia (2007).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The world in a grain of Canvey Island sand

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?