‘I don’t know what I want to be. Is that OK?’

Identity Status Theory suggests that identity formation involves two stages: exploration and commitment. This can help explain how students view their own futures

You may also like

Student A

“I have no idea what I want to be.”

Even with the most interesting self-exploration activity possible in front of them, the student just stares blankly at us, without motivation or interest.

Student B

On the opposite side of the spectrum, we may also encounter the student who claims: “I have wanted to be a doctor ever since I witnessed my [insert relative here] recover from their injury when I was five.”

Cue parents who nod approvingly.

Student C

And there’s the indecisive one interested in everything: “I want to be a lawyer, or a doctor, or an entrepreneur. Or actually maybe an architect? They are all super interesting.”

Do those scenarios sound familiar to you? These students are all at different stages of exploring and committing to an identity.

There’s a psychological framework to help us think about these cases, proposed by a psychologist named James Marcia.

This article will dive into Marcia’s Identity Status Theory, as well as exploring ways that counsellors can apply this in our work, with the goal of helping students find their career identity.

Finding yourself: Identity Status Theory

If you study developmental psychology, you will definitely learn about Erik Erikson. He was the seminal developmental psychologist who proposed the idea of psychosocial development. Quickly summarised, this idea suggests that at different stages of life, there is a task or a conflict we need to resolve. At the stage of adolescence, the task is to work through the complexities of finding one’s own identity, and is titled: “identity versus role confusion” (all of Erikson’s tasks are titled A versus B).

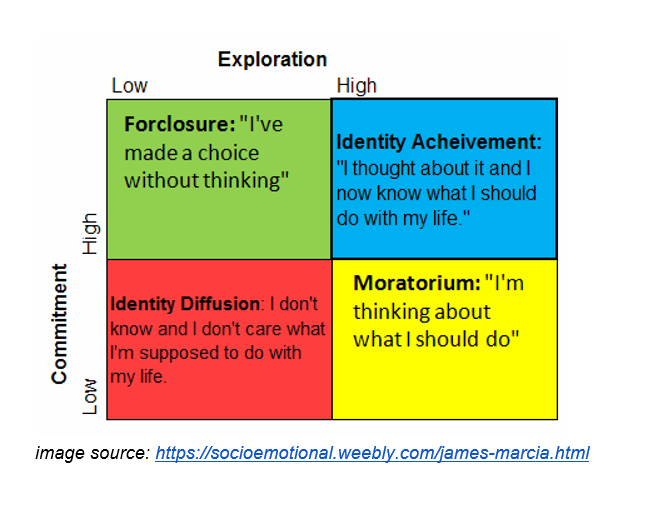

Marcia further developed Erikson’s idea of psychosocial development. He posited that identity formation involves two components: exploration of and commitment to an identity. This is not just restricted to finding one’s career but can be about religion, politics, relationships and even gender roles. However, for the purpose of this article, we will focus on careers.

Let’s first clarify the two components: exploration and commitment.

Exploration is whether you have or are engaged in searching for your identities, which may involve trying things out.

Commitment is whether you have decided on a certain identity or not.

Within these two dimensions, four different statuses can be created. Visualise an individual who has: explored but not yet committed; committed but not yet explored; explored and committed; neither explored nor committed.

Identity diffusion: low exploration, low commitment

Identity foreclosure: low exploration, high commitment

Identity moratorium: high exploration, low commitment

Identity achievement: high exploration, high commitment.

Let’s visualise this in an image.

The student scenarios at the start of this article were actually written to match these types. Try visualising a student who matches each category as you read through a further elaboration of the types.

Identity diffusion: low exploration, low commitment

Think of Student A, who stared back blankly at us even when presented with four types of personality and strengths assessments. This status corresponds to an individual who has neither explored their identity sufficiently nor committed to one.

This is perfectly normal for children and young adolescents but teenagers are expected to move out of this stage as they explore identities through exposure to role models and experiences that demonstrate possible identities. If diffusion is prolonged, the characteristics that may arise are: low self-esteem, disorganised thinking, procrastination and avoidance of issues and actions. Individuals can also be self-absorbed or self-indulgent, and can seem to be drifting aimlessly.

Identity foreclosure: low exploration, high commitment

Think of Student B, who has known that they wanted to be a doctor since they were five years old. This status is characterised by a commitment to an identity without having engaged in an exploration process. Sometimes the commitment may arise from the anxieties that are inherent in adolescence or from pressure from parents or their culture.

Prolonged foreclosure is associated with characteristics such as strong need for approval, authoritarian parenting style, low levels of tolerance or acceptance of change, a high degree of conformity and conventional thinking.

Identity moratorium: high exploration, low commitment

Think of student C, who wants four completely different careers. This status corresponds to someone who is actively exploring but has not yet committed to any one path.

Naturally, this status can involve anxiety, uncertainty and possibly procrastination or low self-esteem. Hopefully, there will be ample opportunity to try out and model different directions, because identity moratorium can be a precursor to the next status.

Identity achievement: high exploration, high commitment

I didn’t give a student example for this category because it’s difficult for students to have explored sufficiently in high school – there just hasn’t been enough time for it, and much of the exploration can continue in university.

Adults are more likely to fall into this category because they will have explored more and committed to their career. If you have had a squiggly career and have now found college counselling to be a fulfilling and deeply satisfying career that you know you will continue with for the rest of your life, then you have reached identity achievement.

Movement

It’s possible to move through these statuses; an individual usually does not remain in one status and stay there (although that’s also possible). A direction can be in the order that these statuses were listed (diffusion leads to foreclosure leads to moratorium leads to achievement) but it does not necessarily have to be.

In fact, our job as counsellors is to help students move through these statuses to reach identity achievement.

Nuances

Identity status is not global. You may achieve a moratorium for career identity but still be at foreclosure for religious identity and achievement for gender identity. Also, not everyone will always reach identity achievement.

You can also reconsider your commitment after exploring – think, for example, about an adult who makes a career change later in life. This can create a fifth status: searching moratorium. This fits in with how postmodern career theories view career development.

Using identity status theory in our practice

Marcia’s theory is essential for us as college counsellors, because what we’re doing is helping students move through these statuses, even though we may not have thought of it in those exact terms.

Here are some practical tips on how to apply this framework to our practice.

Identify the status and be more understanding of indecision

Perhaps you were previously frustrated by indecision shown by students (“Why can’t they just decide on one career path?”). Now you can frame this as a very natural process of going through the identity moratorium. In fact, this needs to happen so that a student commits to an identity after having explored. Remember that commitment without exploration is foreclosure.

Embed exploration in your curriculum

When we are assigning career tests or strength inventories or organising a career fair or questioning students’ assumptions, we are actually creating an environment where exploration is possible. With knowledge of Marcia’s framework, now you can point out why – we’re ensuring that students can commit to an identity after having sufficiently explored.

Understand that exploration can mean crisis

The two developmental psychologists, Marcia and Erikson, used the term “crisis”. Within their frameworks, it meant circumstances that led them to question their identity and reassess their life.

And, actually, exploration entails crisis and vice versa. Exploration has this positive, adventurous feeling, but the word “crisis” feels distressing. And the journey of finding out who you can be can be positive and exciting at times but distressing at others.

Help students through crisis

Giving up previous notions of what you thought you should or could be can be confusing and difficult. Part of our job is to help students process this and find new identities.

First, let’s validate their experience and tell them that this crisis/exploration and resulting uncertainty is in fact very normal. Telling them about your own experience of crisis or how your career came about unexpectedly and perhaps through hard times may provide further relief and clarity. The point is not figuring it out right away but exploring it continually.

Question students’ assumptions

I used to think – and still hear often – that an identity crisis is a bad thing, or that a student who knows what they want to do is always a good thing.

Sure, a crisis is not a pleasant experience, and some people may certainly be successful and happy pursuing a career they wanted for a long time. But Marcia’s framework shows that an identity crisis and a student not knowing what they want are not necessarily bad things. Perhaps weave this in your conversations with concerned parents, too, who might want immediate certainty on their children’s future.

Remind students that the exploration never ends – and that’s a joyful thing

Think about the new fifth stage of searching moratorium. It’s OK to search after committing. That makes for an exciting life, and in a world that always seems to emphasise the point of arrival, let’s remind our students of the joy of the journey as well.