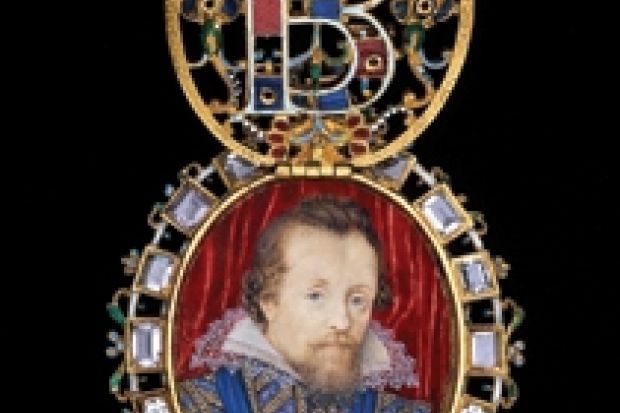

Credit: The Lyte Jewel/Thomas Hilliard/© The Trustees of the British Museum

Shakespeare: Staging the World

British Museum

19 July-25 November

I’ll need to visit this exhibition again, not merely because its 200-odd artefacts as well as their arrangement are compelling but because, with staggering stupidity and unintended irony, I walked right past its most quintessential object. It wasn’t until we were making our way back to the Underground that my companion remarked on the First Folio on display in pride of place, immediately opposite the entrance to the first room. “What Folio? I didn’t notice a Folio there!” In fact, as a second copy was displayed in the exhibition’s last room (open at The Tempest), I just assumed that the curators had kept us waiting for the climax.

But a show about Shakespeare without a Folio would be a bit like an exhibition of Tutankhamun that failed to include the gold death mask or (even worse) attempted, aided by the legerdemain of video projectors and lighting effects, to conjure up the mask as though it were mysteriously present - which is exactly what did happen in the 2004-11 touring exhibition Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. In that case, the Derren Brownesque deception prompted a huge sense of anticlimax, especially among those of us old enough to have been taken (as wide-eyed children) to The Treasures of Tutankhamun at the British Museum in 1972.

So an exhibition of Shakespeare without a First Folio might be accused of lacking a central object - Hamlet without the Prince, you might say. It’s not that I am fetishising the Folio; it is just that Shakespeare’s poetic achievement, the excitement of his vision, the challenge of his empathies, the sheer confrontation of his brilliant imagination is contained in this single book, a book that was recognised, from the time of its earliest editions, to contain something that outstripped any material object, the only book (except the Bible) with which you are allowed to pass your days stranded on a desert - or, as the copy signed by jailed members of the African National Congress so movingly documented, Robben - island.

In his first published poem, which appeared in the Second Folio of 1632, John Milton emphasises how Shakespeare’s supreme achievements will outlive any funereal memorial: “Thou in our wonder and astonishment/Hast built thyself a lasting monument”. The motif is not particularly original; in the Sonnets, Shakespeare himself had opposed the brevity of life against art’s longevity, but Milton’s point is that the contents of this book are sufficient monument to the playwright’s teeming creativity - no need for the ostentation of “piled stones”.

In her impromptu remarks at the press viewing, the exhibition’s co-curator, Dora Thornton, challenged this preoccupation with literary immortality head on: “objects”, she declaimed, “make history as well as texts”. This unabashed emphasis on materiality contests the tyrannical abstractions of literary and cultural theory. The British Museum’s director, Neil MacGregor, has championed this approach by exploring the historical implications of forks, clocks, maps, drawings, hats, mirrors and so on. Indeed, the revelatory attributes of everyday articles allowed him to reveal, in a series of wonderful 15-minute programmes on Radio 4, nothing less than “the history of the world” - an aspiration that carries a daring whiff of hubris, especially when you consider that he attempted to do so armed with a mere 100 objects.

But the emphasis on things rather than ideas, on stuff rather than values, is timely. The tidal swell of Shakespeare is at an all-time high. His oeuvre has just been staged in 37 languages at the Globe theatre in London; BBC Two is currently screening new versions of the history plays (accompanied by programmes on BBC Four presented by Sir Derek Jacobi, David Tennant and Ethan Hawke); James Shapiro, Simon Schama and Francesco da Mosto have recently presented television documentaries about the playwright; and the Royal Shakespeare Company is conspicuously touring its first all-black production - a superb Julius Caesar that was also broadcast on BBC Four in June. James Naughtie, in this Jubilee year, is recounting stories on Radio 4 of The New Elizabethans. We are in the full throes of the World Shakespeare Festival, the London 2012 Festival and the Cultural Olympiad - Shakespeare’s influence, his theatre, his cultural weight, even his delineation of Britishness is (almost) too much with us.

In returning to the possessions of Elizabethans and Jacobeans, and the paraphernalia, some of it trivial, of day-to-day lived experience, this exhibition grounds the rarefied ambitions of “Brand Shakespeare” in the prosaic realities of what Wordsworth called “earth’s diurnal course”. Shakespeare loses his mystique, his ideologically constructed supremacy, and so his works are no longer the preserve of an educated elite. Instead they are shown to converse with the triumphs, hopes, agonies or desires of actual people, rooted in a socio-historical moment as contingent as any other, framed by systems of belief, spheres of knowledge and structures of conviction as liable to be revised and overturned as those of any other time before or since. Shakespeare, the transcendental “Everyman” who speaks to all times and places, is suddenly located, made specific, bounded by the nutshell of his day. This makes him more, rather than less, meaningful.

Thornton and her co-curator, Jonathan Bate, have organised the exhibition around a series of different locations including London, Arden, Venice, medieval England and the Classical world. The exhibition ends by stretching the imaginative horizon as far as the New World and The Tempest. A number of themes run throughout, including that of race: there are items devoted to Venetian Jewry as well as the magnificent portrait of Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun (by artist unknown), the Moroccan ambassador who was in London around 1600 and who may well have been the model for Shakespeare’s Othello.

Another thread is that of cartography. There are maps of the whole country small enough to appear on a playing card, while the Sheldon tapestry map of Warwickshire, with Stratford-upon-Avon clearly marked, occupies an entire wall. The complete panoramic view of London by Wenceslaus Hollar details every single rooftop (although it infamously misidentifies the Globe) while a silver medal designed by Michael Mercator that images Francis Drake’s circumnavigation is less a navigational aid than a haughty piece of anti-Spanish propaganda (it was struck only one year after the defeat of the Armada). The occult is represented by several pamphlets including Daemonologie, James VI and I’s own, as well as a sinister-looking calf’s heart stuck with pins and a witch’s cursing bone.

The exhibition is a co-production with the RSC and perhaps its only irritating feature was the projected presence of actors who repeatedly and intrusively intoned notable speeches: Sir Antony Sher (“Hath not a Jew eyes?”), Dame Harriet Walter (Cleopatra’s suicide), Geoffrey Streatfeild (St Crispin’s day), Sir Ian McKellen (Prospero) and so on. Their performances served to portray, erroneously, the plays as collections of monologues or poetic set pieces. They were also just too loud, making considered digestion of the objects’ descriptive labels that much more difficult.

Finally, the siting of the show itself, in the reading room of the former British Library to which Virginia Woolf mischievously referred as “a huge bald forehead”, was supremely fitting. Shakespeare, with his large bald pate, stares out at us from the Droeshout engraving reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, an iconic image that folds together like the pages of the First Folio, the playwright’s sublime creativity and the material realities that animated it.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?