Grace of Monaco

Directed by Olivier Dahan

Starring Nicole Kidman and Tim Roth

On general release in the UK from 6 June 2014

Grace of Monaco attempts to make various crises out of Grace Kelly’s marriage to Prince Rainier, and to give her life the cinematic genre treatment. The film-makers would have us believe that the conflict over Alfred Hitchcock’s offer to her to play the lead role in Marnie was a melodrama, and the involvement of French President Charles de Gaulle in Monegasque tax affairs was a thriller. The Grimaldi family are unhappy, as were crowds and critics at the Cannes Film Festival last month. There is a very good reason for this. If Kelly is to be seen on screen, she deserves to be seen in her own skin in her own films.

Biopics are peculiar in that they are inevitably selective in the events they cover and usually deploy a self-conscious mimicry in the casting of look- or act-alikes, as in the 1983 biopic Grace Kelly, with Cheryl Ladd as the young star and Ian McShane as a Prince Charming Rainier. Olivier Dahan made the wonderful La Vie en Rose (La môme, 2007), featuring an Oscar-winning performance by Marion Cotillard as the “little sparrow” Edith Piaf. This led to a resurgence of interest in Piaf, but also made a star out of Cotillard. Everyone was amazed to see the beautiful young actor who had played the ageing and prodigiously talented Piaf.

In La Vie en Rose, the life, talent and achievements of Edith Piaf were the story. In Grace of Monaco, however, one of the biggest movie stars in the world, Nicole Kidman, plays the already married Princess Grace, and the story focuses on a period in her life after her film-making years are behind her. The star persona of Grace Kelly herself, the Oscar-winning leading lady, is elided from the film altogether, as Kidman enacts a chocolate-box vision of a bone china princess doll. (It is actually possible to buy a bone china doll of Grace Kelly, so there clearly is some demand for this incarnation.)

A good deal more of Kelly the actor was on show in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Grace Kelly – Style Icon exhibition in 2010. A collection of her costumes and accessories offered traces not only of the woman herself but also of the characters she played and the performances she gave in the 11 films she made in Hollywood between 1951 and 1956. The emphasis on fashion attests to the way in which Kelly is most frequently encountered today, as an icon of timeless style and class. Her glamorous and stylish on-screen costumes and her preppy off-screen wardrobe mean that she remains a go-to icon for women’s magazines in their construction of beacons of fashion supremacy. From the golden fiesta of her ballgown in To Catch a Thief (1955) to her loafers, jeans and coral shirt at the end of Rear Window (1954) and even her simple but classy beige silk shirt and trousers in Charles Walters’ High Society (1956), Kelly’s film costumes are timeless. The vitality of these costumes, however, can be appreciated only by watching the lithe and mischievous Kelly inhabit them on screen. Playing the “fair Miss Frigidaire” that Frank Sinatra seduces on the eve of her wedding in Walters’ film, Kelly demonstrates her star persona at its richest: full of humour, physicality and intelligence.

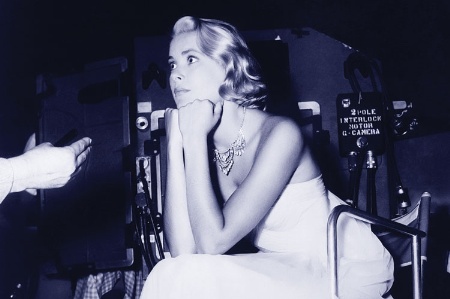

Some movie stars can be recognised by a few brushstrokes on a page. The sleepy eyes, widow’s peak, beauty spot and parted pouting lips of Marilyn Monroe, for example, swiftly evoke the languid sensuality of her photographic image and pin-up persona. Likewise, the doe eyes, defined dark eyebrows and gently flaring nostrils of Audrey Hepburn’s face can easily convey the individuality of her image, as they do in Fred Astaire’s photographic enlargement of her features in Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957). Grace Kelly’s persona is not so easily captured.

Although she was a cover girl a million times over, Kelly’s multifaceted persona consists of a plethora of tensions: virginal blonde in white gloves and serial seducer of leading men; all-American gal who loved cheeseburgers and baseball, and cool princess with European flair; Catholic girl and sexual dilettante; career woman and Cinderella bride. These apparently contradictory elements are evident not only in her personal life but also in some of her most successful screen characters. In her Golden Globe-winning role in John Ford’s Mogambo (1953), Kelly plays a young English wife turned on by the hothouse of passion and masculinity in Clark Gable’s safari camp, her bewitchingly ladylike eroticism enticing Gable away from the more obvious and earthy charms of Ava Gardner.

In the first of three collaborations with Hitchcock, Dial M for Murder (1954), Kelly plays adulterous wife Margot, unwittingly negotiating the passions of her ex-lover and her murderous husband, and killing the hired assassin to boot. It is perhaps in her next Hitchcock film, Rear Window (1954), that we first see the wonderful humour and lightness that Kelly could bring to the screen. Posing tantalisingly in front of a temporarily wheelchair-bound James Stewart, Kelly floats around his apartment in glorious silky nightwear, offering a “preview of coming attractions”. Here Kelly oozes sophistication and self-confidence as well as physical bravery – she clambers across the courtyard to investigate the apartment of the suspected killer – and appealing duplicity, as she returns to her favoured Harper’s Bazaar once Stewart has fallen asleep and she can stop pretending to be gripped by Beyond the High Himalayas.

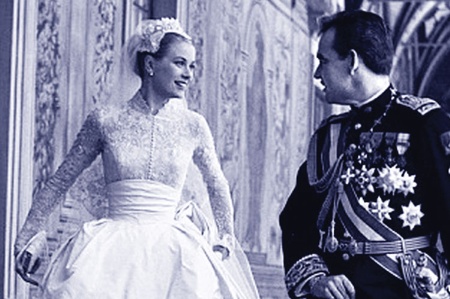

In George Seaton’s 1954 film The Country Girl, Kelly plays a woman who is not glamorous or lively, but who struggles with the realities of marriage to an alcoholic. The weight of the death of their child hangs over their every moment. Kelly won an Oscar for this role, and it is remarkable to see her on screen stripped of the colour and lightness that characterises many of her other performances. It is her third Hitchcock film, To Catch a Thief (1955), that cements her place in the history of Cannes, for it marked the beginning of her involvement with Monaco and Prince Rainier. Not only does her character, Francie Stevens, pick out the “little pink and green buildings” of the palace when picnicking high above them with Cary Grant, but she also, chillingly, is seen driving helter-skelter around the hairpin bends of the Grand Corniche, prefiguring Kelly’s death on a nearby road in 1982 at the age of 52.

It was during the Cannes Film Festival in 1955 that Kelly was first introduced to Prince Rainier during a photo shoot at the palace, marking the beginning of a courtship that led to marriage in April 1956. During her engagement Kelly played her last two film roles, as a princess facing up to the restrictions of her life of duty in Charles Vidor’s The Swan, and as a socialite succumbing to the pull of her more earthy nature in High Society (both 1956). These roles demonstrate her willingness to be self-reflexive as well as showcasing performances of balletic poise, vocal dexterity and generic nuance.

Not all Kelly’s performances were top-drawer: she is too young to play Gary Cooper’s pacifist bride in Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), given limited opportunity to develop a character as William Holden’s shore-leave wife in Mark Robson’s The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954), and one of the cast of uncomfortables in Andrew Marton’s potboiler Green Fire (1954).

Watching Kelly on screen, however, frees her image from the domineering discourses of being Hitchcock’s ideal blonde, a princess bride, a fashion icon or the subject of a dubious biopic. In her short film career, she created a body of work that deserves to be viewed as the reason for the stratospheric nature of her impact on Hollywood and the basis for the longevity of her star image. If you want to see a film that tells you about Grace Kelly, then watch one with her in it.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?