Source: Miles Cole

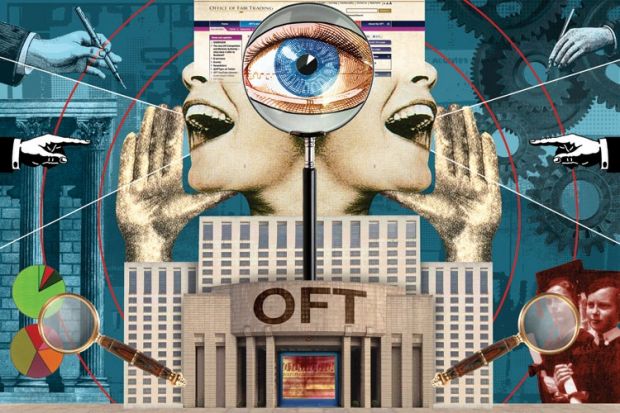

The Office of Fair Trading produced an early Christmas present for universities last week by announcing a “call for information on the provision of undergraduate higher education in England”.

The OFT says it is keen to gain a better understanding of whether universities are able to compete and respond to students’ increased expectations, and whether students are able to make well-informed decisions, which would help to drive competition. It is particularly interested in receiving information about how universities compete with each other, the impact regulation has on universities and the student experience of the system. The deadline for submitting information is noon on 31 December (just in case no one has anything to do after the research excellence framework submissions), and the OFT intends to publish a summary of its findings, including potential next steps, in March 2014.

Although the announcement was relatively low-key, it could herald a change in universities’ relationships with the competition authorities.

The OFT is an independent public agency with powers to enforce both competition and consumer law. Indeed, in this second role it is investigating the fairness of university contracts, notably the refusal to issue degrees if a student still has outstanding debts to their university. The OFT has received a fair amount of criticism in the past for its enforcement record and priorities, not least from the government, so I suspect that it is opening this inquiry because it believes that there are some issues that need to be tackled. Although it will be replaced in April 2014 by a new body, the Competition and Markets Authority, this does not mean that any inquiry will cease, as many OFT staff will simply move to the CMA.

What, then, are the possible outcomes? The CMA could launch a market inquiry into the university sector as a whole, or aspects of it. In the past this has often been the prelude to an in-depth market investigation by the Competition Commission (another independent body to be replaced by the CMA), which would take 18 months to two years and could require significant changes. It was, for example, as a result of a Competition Commission inquiry that the British Airports Authority was required to sell off Gatwick and Stansted. Certainly any market investigation into the university sector would examine, probably as a central issue, the effect of the tuition fee cap and how universities decide on their fees.

As an alternative to a market investigation, the CMA could initiate competition enforcement proceedings that could result in the imposition of hefty penalties (up to 10 per cent of a university’s annual turnover) on institutions found guilty of breaching competition law or even, in the most egregious cases, to the criminal prosecution of individuals. If a breach of competition law was shown, this could also be followed up by private actions for compensation either individual or collective under the government’s planned changes (think of the National Union of Students, for example). Although criminal prosecutions might seem unlikely, there may well be arrangements within the university system that the CMA would think warrant further scrutiny; a perfect example could be the rule that prevents potential undergraduates from applying to both Oxford and Cambridge in the same year, which Times Higher Education recently reported on.

Finally, the OFT may end up giving advice to the government or guidance to universities and/or students. It might also seek voluntary action from universities. The word “voluntary” in this context is misleading: it means, “if you do not act in a way we regard as proper, we will make other arrangements.” This would quite likely open the sector to a long-term discussion with the CMA over various matters. This has been the experience in banking, where the OFT started its first inquiries in 2007 and where its programme of work continues.

Of course, the application of competition law to universities and the university sector is not new. Way back in 2005, the merger of the Victoria University of Manchester and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology was reviewed by the OFT. THE has also reported numerous instances of competition law concerns recently, for example, regarding course-by-course breakdowns of how tuition fees are spent.

The prospect of an actual competition case or inquiry, which would be complicated, expensive, time-consuming and would require significant time investment by senior management, should not be taken lightly. More positively, it would provide an opportunity to put the case against regulatory arrangements that restrict the freedom of action of universities. However, as the NHS discovered this month when the Competition Commission blocked the proposed merger between hospital trusts in Bournemouth and Poole, an approach that seems common-sense and rational within a sector may not withstand scrutiny by a competition authority.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?