Teresa of Avila, that 16th-century mystic, visionary and reformer of the Carmelite order, has always been a figure to spark debate.

Dismissed as a hysteric for her visions, emulated for her mystical union with God in prayer, applauded for her reform of convent life, she was created a Doctor of the Church only in 1970, by Pope Paul VI. In this book, written in anticipation of the 500th anniversary of her birth in 2015, Peter Tyler regards this state of affairs as unsurprising, given the challenges that her mystical language presents. In describing union with God, Teresa was “trying to articulate what is frankly unsayable” – the encounter of the soul with the transcendent.

The Anglican scholar W. R. Inge, in his influential Bampton Lectures on Christian mysticism in 1899, argued dismissively that it was not worth giving a detailed account of Teresa’s mystical theology; it was for her life and her piety that she should be studied. Tyler rescues her from such partial (and, one might say, gendered) praise, arguing that it is for the intellectual rigour with which Teresa explores the landscape of the soul that she deserves to be called a “doctor of the soul”.

From the opening chapter, Tyler plunges straight in to Teresa’s language, looking at the difficulties of translating her work, and her style. Readers unfamiliar with Teresa the writer, or indeed Teresa the woman, may find this disorientating, but they should persist. Tyler gets into his stride and furnishes a stimulating discussion of Teresa’s context and writings and her contemporary relevance, drawing on a wide range of scholarship.

Teresa was always at pains to emphasise her Christian credentials, bolstered by seven brothers who were conquistadors engaged in the re-Christianisation of Spain after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. However, recent research on her family suggests that she came from converso stock. Her convent was built on the old Jewish cemetery of Avila and this means, as Tyler poignantly reminds us, that Teresa spent “most of her life literally living over the remains of her ancestors”.

She was 20 in 1535 when she entered the Carmelite convent of Encarnación. It was full of the daughters of wealthy Avila families and Teresa found it a lax establishment: the Rule was not kept in its “primal rigour”, and the nuns came and went as they pleased. Teresa wrote that the freedom of the lack of enclosure did her great harm. With friends, she set about living a simpler life, following the ideals of the first desert Carmelites; their success led to permission to found more Carmelite houses.

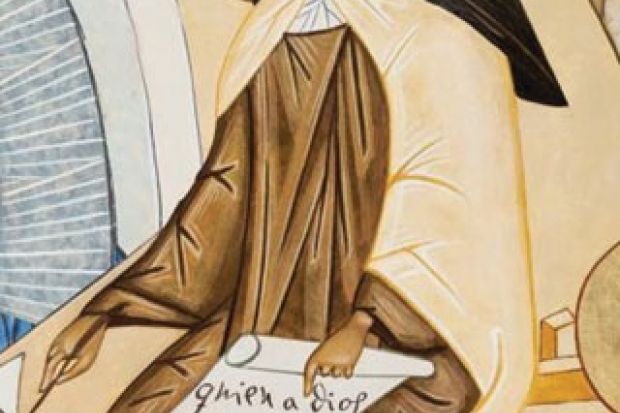

The Book of the Life was the most famous of Teresa’s writings. There she wrote as “the most embodied of saints”, repeatedly using the words gusto, meaning delight or sensuality, and regalo, meaning caress, when she talked of God entering her soul. Many commentators have reduced Teresa to her embodied raptures – most famously, Jacques Lacan, remarking on Bernini’s sculpture of Teresa in ecstasy. But Tyler offers a more subtle and emotionally intelligent reading of Teresa’s language of the spirit as “neither wholly spiritual nor wholly sensual” but with an ambiguity that invites us into a liminal space “where we must drop all pretence and subservience to the ego”.

In the Book of the Foundations and The Way of Perfection, Teresa’s attention turned from ecstasies of union with God and towards the fruits of mystical prayer in good works and service in the community. The Interior Castle, written in a few months in 1577, was the culmination of all her writings; her mature mystical theology. Here she drew on the scholastic mystical theological tradition as well as her own experiences of prayer and writing.

Tyler’s focus is not devotional, but his final two chapters attempt to show the relevance of Teresa’s work today by relating it to Jung and psychology, Buddhism and mindfulness. These are rather cursory and do not add to the text as a whole, but nor do they undermine what is the strength of Tyler’s work – namely, a sophisticated and engaging analysis of Teresa’s use of language as she tried to write her experience of God. Tyler succeeds beautifully in relating Teresa’s choice of words to her religious experience, and thus laying out with context and clarity her mystical theology.

Teresa of Avila, Doctor of the Soul

By Peter Tyler

Bloomsbury, 240pp, £18.99

ISBN 9781441187840

Published 13 February 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?