The word “grace”, like “beauty”, is not much used these days, when Arts Council apparatchiks claim that “art” and “artist” make people “uncomfortable”, and insist that the term “creative practitioners” should supersede “artists”. To students of the Italian Renaissance, however, “art” and “artist” present no such difficulties, for in environments positively dripping with artistic wonders on every side, there can be no doubting the ineffable presence of grace in works that strike viewers dumb, move them to the core of their being or bring them to their knees.

Yet one of the problems with the word “grace” is that it is elusive. It can refer to pleasing qualities or features; attractiveness and seemliness; ease and refinement of movement, action or expression; one of the sister-goddesses regarded as bestowers of beauty and charm, the Three Graces; favour, favourable or benignant regard; the condition of being favoured; a privilege or dispensation; regenerating and sanctifying divine influence in humans, inspiring virtuous behaviour; the condition of a person under divine influence, that is “in a state of Grace”; a formal pardon; a courtesy title; thanks and thanksgiving, asking a blessing before or after a meal; and much more.

Certainly the Three Graces attracted the attention of many artists in the past, not least during the Renaissance, and during the 19th century grace seems to have been more easily identifiable than is the case today. It was understood by luminaries such as Ludwig Grüner, art-adviser to Prince Albert, particularly in relation to the creations of Raphael, revered especially in Germany. It is also obvious that grace was understood by Richard Wagner, whose last great work for the stage, Parsifal, is shot through with it in its many redemptive aspects.

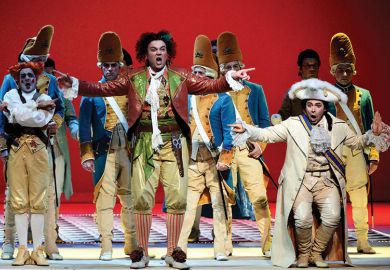

The extraordinary Vorspiel to Wagner’s Lohengrin (the swan-knight son of Parsifal) suggests supernatural grace, and indeed the swan that tows the knight across the waters has links with Venus’ swans drawing her float from which the goddess claimed her victory over Mars, celebrated in the fresco the Allegory of April in the Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara. Ita Mac Carthy uncovers all sorts of connections at a time in Italy concerned with what might be described as the reactivation of aspects of the classical past, drawing on the writings of Tullia d’Aragona, Ariosto, Vittoria Colonna and others, and exploring works by Francesco del Cossa, Michelangelo and Raphael. Throughout, she puts grace at the centre of things, even though it is notoriously difficult to define, endeavouring to show what it signified at the time, and how it permeated style, behaviour and notions concerning society and even salvation.

However, Mac Carthy’s book is too long. Repetitions abound: the same epigraph occurs on pages 12 and 181, and some images appear on one page in black and white and on another in colour. This is a pity, for her writing is erudite, perceptive and intelligent, perceiving grace in all its complexities and how it informed the Italian Renaissance. Moreover, it did not die with Raphael, as some have claimed: Mac Carthy shows that it went to ground, then flourished again under more favourable skies. In today’s educational climate, however, in which the Renaissance and grace apparently mean very little to many school-leavers, I fear the firmament is permanently overcast.

James Stevens Curl’s Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism was published in 2019. In the same year, he was honoured with an Arthur Ross Award for Excellence in the Classical Tradition for History & Writing by the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art in the US.

The Grace of the Italian Renaissance

By Ita Mac Carthy

Princeton University Press, 264pp, £30.00

ISBN 9780691175485

Published 4 February 2020

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?