Some books burrow into your heart and mind the moment you hold them. Even before I opened Book of Beasts, I was mesmerised by the contrasting textures and visual dynamics of the cover. A seamless blend of material and soft-touch lamination, Kurt Hauser’s stunning design guides the hand and eye past a family of charming lions, poised to leap off the bright boards, and across a unicorn resting amidst the thousand tiny flowers that wrap around the spine.

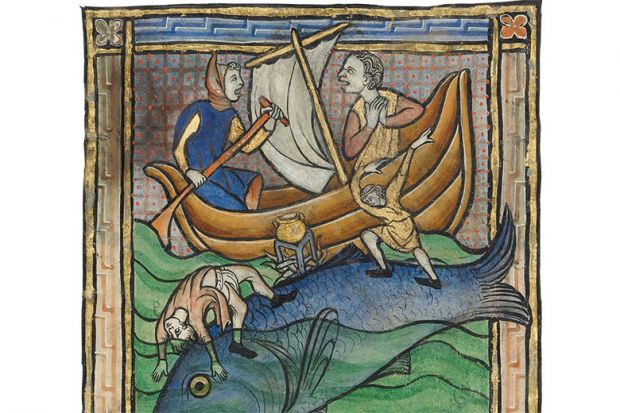

It was only upon completing my journey through this weighty tome that I realised that the hybridity of the cover pays subtle homage to the themes and ideas explored throughout the contents. A delicious accompaniment to the Getty Museum’s new exhibition on the art of bestiaries, Book of Beasts turns on the intersection of opposites: past and present, text and image, sacred and profane, real and imagined, human and animal. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the introduction’s swift movement from the well-known purity of the unicorn to the noxious, three-acre-long fart issued by the bonnacon, an inscrutable creature, which delighted and disgusted readers in equal measure.

Showcasing the work of 26 scholars in an array of specially commissioned essays that “celebrate the visual contributions of the medieval bestiary to the history of art”, this accessible collection offers fresh insights into the development of these fascinating artefacts and their legacy. Beyond this, it encourages readers to draw their own connections between the “glittering array” of manuscripts, ivories, tapestries, metalwork, jewellery and sculpture featured in the exhibition.

Throughout the three (unequal) parts, discussion often centres on the most common and thought-provoking beasts – the unicorn, lion, pelican, dragon and whale – each of which functioned as an avatar of Christ or the devil in medieval devotional practice. For readers with little or no experience of bestiaries, such limitation allows each essay and catalogue entry to demonstrate how animals articulated the medieval worldview, or to track the bestiary’s indefatigable resonances today in works such as Damien Hirst’s Skull of a Unicorn (2010). Yet Book of Beasts also delivers for those familiar with bestiaries by tackling knottier issues, such as who commissioned and read the richly illustrated manuscripts, and why medieval artists ignored the visual cues in the text to draw scenes of their own devising. Two of the most successful essays are those by Elizabeth Morrison and Susan Crane, who conjure the humanity behind the books by focusing on tiny differences in the manuscripts’ image sequences which point to the artists’ genuine affection for the stags, hedgehogs, cats and other creatures they painted.

In this respect, Book of Beasts becomes more than a luxurious souvenir of the Getty’s exhibition, or a beautiful consolation prize for those unable to attend. It genuinely breaks new ground by engaging with the bestiary’s role in the “pictorial shorthand…that permeated the visual culture of the Middle Ages”. Like the manuscripts it considers, the book is a feast for the eye and a breath-taking cache of knowledge, which offers a much-needed balance to pre-existing scholarship on the bestiary’s textual history.

Sarah Peverley is professor of English at the University of Liverpool.

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World

Edited by Elizabeth Morrison with Larisa Grollemond

Getty Publications, 354pp, £45.00

ISBN 9781606065907

Published 6 June 2019

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: From unicorns to beastly farts

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?