The commitment to reduce net inward migration to the tens of thousands was announced almost by accident. Yet it has been a sacred text of the Cameron and May eras in the UK.

The inclusion of international students in the target is the single most silly higher education policy I have come across in more than a decade working in the sector. International students come here, spend lots of money and then go home again, usually with warm thoughts about the UK. What’s not to like?

The advocates of the target tell universities not to worry. There is no limit on international students, they parrot. That is true but it ignores the killer fact that the target makes it harder to convince people in other countries to come and study here. The government’s position is to want less net inward migration – or, more colloquially, “a hostile environment”. Their desire to have fewer people from other countries studying here and staying here to work afterwards has been proven time and again through various new restrictions.

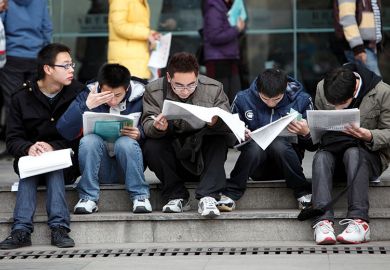

The fact that the number of international students has stagnated rather than collapsed is a testament to the quality of our universities. But without the target, we could have seen the sort of growth enjoyed in Australia, which is overtaking us a destination of choice despite having a much smaller population, fewer universities and a less prestigious higher education system. As a result of our free choice to dampen demand, our university campuses are less diverse than they otherwise would have been, limiting the educational, economic and soft power benefits.

I once asked a senior Home Office civil servant why he thought that politicians should keep students in the target despite the public’s support for international students. He said that, whatever voters may say, they don’t like hearing foreign voices on the street and, when they do hear them, they don’t know if the speaker is a student or not. So, he argued, it is best to keep out as many people as possible. If that’s not institutionalising racism, I don’t know what is.

As a result of giving the Home Office complete control over student migration, there are big contradictions at the heart of policy. For example, educating international students is the only thing universities do that makes a clear surplus. So the target directly hinders the Government’s own goal of raising research and development spending to 2.4 per cent of GDP.

One of the specific disincentives put in the way of people who are interested in coming to study in the UK is the tighter restrictions on post-study work rights. This has had a dramatic impact on demand from some Asian countries. Indian students, for example, particularly valued the opportunity to gain experience in the UK labour market before returning home.

In our competitors, they see things differently. In Germany, when they assess the contribution of international students, they include the contributions made from former international students who stay and work on the positive side of the equation. Here, we opt to see them as a problem.

Perhaps this is valid. Perhaps those who stay in the UK take jobs from British people and make little real contribution to the economy. The Migration Advisory Committee seems to think so. Its report on international students rejected the idea of a longer post-study work period because “the earnings of some graduates who remain in the UK seem surprisingly low and it is likely that those who would benefit from a longer period to find a graduate level job are not the most highly skilled”.

So the Higher Education Policy Institute and Kaplan commissioned London Economics to test this hypothesis and to fill in the acknowledged gaps in evidence. The results are very clear. The small minority of international students who stay here from just one cohort are bringing benefits worth more than £3 billion to the UK exchequer. Moreover, they are typically qualified to work in shortage areas so are not taking jobs from Brits.

To top it all, the decision to impose new obstacles in the way of those who wish to work here costs £150 million a year in revenue foregone – or about £1 billion in total since the extra restrictions were put in place in 2012.

John Maynard Keynes is reputed to have said, “When the facts change, I change my mind.” Now that we have a secure evidence base to show the benefits of post-study work, it is time for the Migration Advisory Committee to do the same.

Nick Hillman is director of the Higher Education Policy Institute.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?