Written feedback for students – keep it clear, constructive and to the point

You may also like

Written feedback to and for students is crucial for their learning. Assessments are there to test student understanding and reward them for their ability to deliver against set criteria and/or a brief. In this short reflection, I want to provide practical tips on how to offer effective commentary on assignments, ones that reward positives and offer concrete suggestions for future improvement. That said, this is a personal account reflecting how I do it – there are certainly other, no doubt equally effective, ways of communicating written feedback to students.

Tips on feedback for students

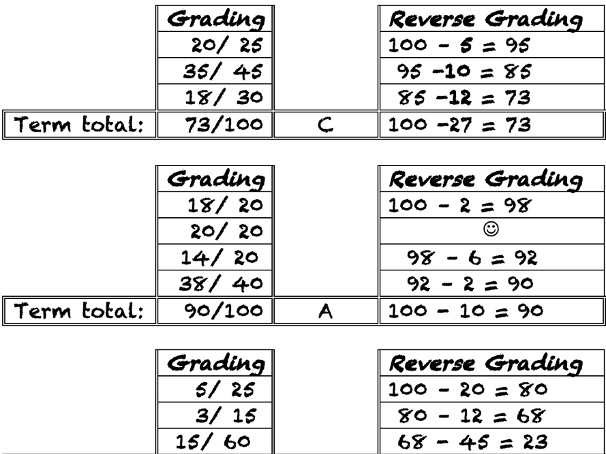

For years, I used to build a mark and feedback from zero upwards – but I came to question this “guilty until proven innocent” approach. So now I start with a perfect assignment in front of me and use words – in-text and in overall feedback – to work down from 100 per cent to a final mark. I find that this device forces me to really question, for example, why I have deducted the marks that I have. I also try to give a clear signal to the student reader by aligning mark and words. For example, a mark in the 40s I would describe as “fair”; in the 50s “this is a good piece of work”; 60s “very good”; 70s “excellent”; 80+ “outstanding”.

− Start by reminding yourself of the marking criteria (from the module guide) and use these in a Word document as subheads that enable you to electronically mark an assignment while reading the submission.

− Then read the bibliography/reference list to see the extent of reading around the topic and the degree to which key works have been used. Then comment positively or negatively on how well-informed and supported the work is.

− Give in-text feedback – such as “ref?” or “spelling?” – and use these to populate the sub-headings in your overall summary feedback before methodically working up to awarding an overall mark.

− Sometimes it’s useful to give bullet-pointed overall feedback for students, using different colours or types of bullet marks. For example, a green tick for good points, with accompanying text, or perhaps a mauve minus and text for a missing or negative point

Seek to offer balanced feedback that is acknowledging positives where at all possible but also drawing attention to negatives and – crucially – to what the student might do about deficiencies in future submissions. Furthermore, try to mark over a block of time. I aim for two to three hours, because I find that anything less makes it difficult to get into the zone/a rhythm, and anything more prejudices my concentration and therefore the likelihood of doing right by a student’s work.

I also vary the way I provide feedback for students, for example sometimes returning a podcast/voice file, bearing in mind that it’s “horses for courses” – always use a feedback style appropriate to the task. Meanwhile, feedback and feedforward are useful ways/subheads under which to review the work and preview ways to make future assignments better.

Also, try to put yourself in the student’s shoes in terms of how you express your comments, keeping in mind the importance of constructive criticism. Additionally, be sure to mark the work in front of you rather than “marking the student” (if submissions are not anonymously presented).

- Want to know how your class is going? Ask your students

- A simple feedback strategy centred on a pedagogy of care

- Campus webinar: Getting digital assessment right

Similarly, always mark against what was asked for, and do not have a secret set of criteria that weren’t in the brief. It’s not a game of poker, where the hand is disguised, but rather a game of snap, where the trick is to align answer with question.

Even after 40-plus years in this career, I still experience “impostor syndrome” in which I question my capability for doing a decent job with marking and feedback. Unpleasant though this is, it invariably passes and reminds me of the importance of deploying a certain humility and kindness in communicating back to the student.

As well as individual written feedback for students, it can be useful to save some generic themes drawn from dos and don’ts that have regularly cropped up in module assessments. For example, spell-checking, not assuming knowledge on the part of the reader/marker, making sure an argument follows a logical flow and so on. I talk these through at the beginning of a class (whether face-to-face or online) and following mark release, encouraging the class to ask me for clarifications if points are unclear. Additionally, I post my comments on the module virtual learning environment (VLE).

Conclusion and student insights

As far as possible, the aim in giving feedback is to enable the student to understand where their work went right and wrong, to clearly be able to connect your commentary with constituent and overall marks given and to see how future submissions can be improved.

Finally, here are some useful things to remember, based on undergraduate insights into the assignment feedback they receive:

− Recognise how the student is likely to receive feedback, because they are likely to be anxious about it – and vulnerable − so might easily be discouraged or disheartened unless words are chosen carefully.

− Recognise the difference between objectivity and comparison − reading a very good piece of work might inadvertently colour the marker’s impression of those following, so take a short break between these to minimise comparison.

− Offer an opportunity for students to query feedback – on the basis that the recipient has not understood it, doesn’t believe it to be true or thinks the tutor has misunderstood a point. To work well, this relationship needs to be respectful and professional but not intimidating, so the student feels able to clarify feedback.

− It is useful to periodically explain how the mark scheme works in HE. For example, that 100 per cent is probably never achievable and that a mark of 70 per cent or more is excellent/outstanding.

James Derounian is a national teaching fellow who lectures on the community governance courses run in partnership between the Society of Local Council Clerks and De Montfort University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.