How to improve digital accessibility at your institution

You may also like

A report by the Central Digital & Data Office (CDDO) on compliance with the digital accessibility regulations for public sector websites and mobile apps identified accessibility issues on nearly all the websites tested.

Organisations have been given about 12 weeks to address any issues found, with 59 per cent fixing them or putting a short-term plan in place. The basic principles of digital accessibility are that organisations ensure their websites, systems and applications are accessible for users by being perceivable, operable, understandable and robust.

For educational institutions, it means ensuring we prioritise accessibility for websites and mobile apps, publish accessibility statements to provide transparent information and signpost support, and take practical steps to train staff and share good practice.

- Online alone is not the answer – how to design remote courses with accessibility and inclusivity in mind

- Making online learning accessible for students with disabilities

- New rules on lecture transcripts give academics an impossible choice

What are examples of the challenges?

Common issues that people with health conditions or impairments experience when accessing content on websites or mobile apps are:

- Lack of closed captioning renders video content inaccessible to people who are deaf or hard of hearing – for anyone to understand this perspective, I’ll encourage you to start a video on mute and see if you are able to make sense of the content without the aid of captions.

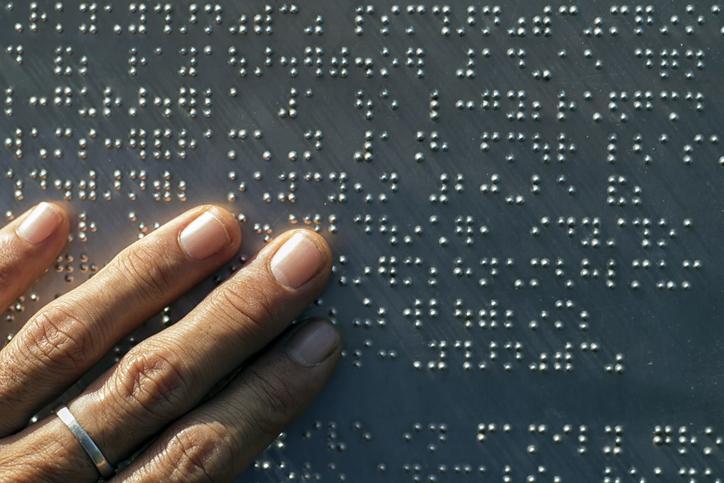

- Lack of alt text on images renders those who rely on screen readers unable to understand or engage with your content.

- Lack of headings make it difficult for users to understand the structure of your work. It is even harder for those who use screen readers to make sense of a document where the headings have not been appropriately signposted.

You can learn more about these issues in a post by Equidox. The main issues identified by the CDDO report are lack of visible focus, which is important for keyboard users unable to use a mouse; low colour contrast, which is important for those with visual impairment; parsing issues – where the underlying code isn’t written in the standards that browsers and assistive technologies can read, thus affecting users of assistive technology such as screen readers; and inaccessible PDFs.

What can institutions do?

Here are three essential steps for making progress towards better digital accessibility:

1. Conduct compliance checks and take action

The first step should focus on checking which systems are in scope, whether each has an accessibility statement, understanding the level of compliance with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), and producing statements or information on your website for each system. This part of the work cannot be understated and requires time. We reached out to some of our products’ suppliers to request their accessibility statements, or to query certain aspects that required clarity. This stage was compliance-driven and is still ongoing. Starting with this stage enabled us to learn and engage with internal and external stakeholders, which then allowed us to be clear on the remit for monitoring and oversight.

2. Create structures for monitoring and oversight

Set up a working group with members drawn from various areas of the university to oversee digital accessibility matters, ensuring regulatory compliance, risk management and promotion of good practice. The group should include “champions” from all areas – academic institutes, research institutes, and professional services areas. We relied on guidance from Jisc, disability support expertise, digital accessibility expertise and sector-level discussions to develop a methodology to improve accessibility across our websites and apps. Our working group reports its work to a central committee as well as relevant steering groups.

3. Embed into strategy and institutional processes

This is about a strategic shift where digital accessibility is seen as essential to the institution’s education strategy. Our efforts are focused on moving towards an equitable and user-driven approach. An article by UX specialist Frank Spillers explains that “accommodations” means, “this person has a disability and therefore needs to be accommodated” and although well-intentioned, this approach is often reactive rather than proactive. Accessibility compliance should be a priority area for consideration when reviewing new systems or platforms that will be accessible via a website or mobile app.

We ensure that accessibility is at the heart of our educational technology procurement and monitoring process. We do this by asking that difficult question – this system or platform is useful but is it accessible? If it isn’t accessible, does the supplier have a road map to make it accessible and are they committed to it?

Another approach is to ensure that content produced for websites and apps is accessible by design. We have rolled out mandatory training for all staff to facilitate this and have made it part of the induction process for new staff. The uptake and feedback have been positive, so we know we are moving in the right direction.

What next?

At the heart of this is the need for an inclusive and accessible teaching and learning experience for all. We must ensure the technologies we rely upon to support and enhance education do not have the unintended consequence of marginalising certain individuals. Improved digital accessibility enhances the user experience for everyone – staff, students, and other users. This is vital at a time when the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development sees technology as a tool for embedding technical competencies in the curriculum. The work is not complete and there’s more to be done.

Baba Sheba is a reader and head of the Centre for Technology in Education at St George’s, University of London.

If you’d like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.