How to create an inclusive learning environment for visually impaired students

You may also like

Popular resources

Think back to choosing your university, securing your place, finding accommodation, making friends, keeping up with the workload and looking after yourself as an independent adult for the first time. Then imagine trying to do all this as a visually impaired person. Achieving all those milestones is still possible, but never underestimate that as an educator you can transform how a visually impaired student feels about their degree.

Despite the efforts of organisations such as the UK’s RNIB, Royal National Institute of Blind People and the Government Equality and Diversity Act of 2010, statistics for sight-impaired and severely sight-impaired students accessing and remaining in higher education still make for disheartening reading.

- Where are the leaders with a disability in higher education?

- New norms in higher education that can help disabled students long-term

- Spotlight: Routes to improving disability support in higher education

More students are progressing to specialist further education colleges, such as Queen Alexandra College in Birmingham, but the still-tiny proportion of visually impaired students in higher education is an issue that must be addressed.

I was registered as blind in 2000. I made it through my undergraduate degree, my master’s and my doctorate as a sight-impaired student, encountering the isolation, the lack of access to course material and the self-consciousness and anxiety that went hand in hand with sight loss. I made use of whatever resources in alternative formats I could find: I bought audiobooks, recorded Open University programmes from the radio and the television and made voice recordings of my ideas for assessments and exams.

In the UK, the disabled students’ allowance (DSA) had existed since 1993, but none of my lecturers or university staff knew of this invaluable resource. Some thought I was “unusual” to be at university at all.

Once I was given my certificate of vision impairment, doors began to open. The first gave me access to the RNIB’s talking books library, which continues to strive for equality for all sight-impaired individuals. I would encourage any lecturers to suggest this to their sight-impaired students. The library offers thousands of titles as digital downloads, via streaming through an Alexa device, as Braille documents or on a USB stick. It also offers one of the most extensive Braille and large-print music score collections in the world. These will all be represented as part of the student’s bibliography and is adjusted to the lecturer’s own style of referencing.

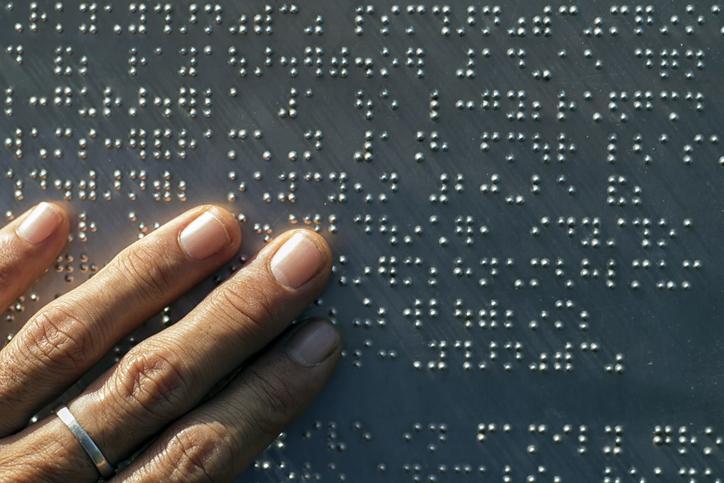

Embrace the innovation that is Braille

Braille ensures that any source of information that is available in the printed word – whether a scientific journal, a music score, a conference paper, a campus map or a work of literature – is accessible to visually impaired scholars.

While conducting my research for this series of articles, I discovered a number of students, academics and lecturers who work with Braille and want to share their enthusiasm and respect for Louis Braille’s innovation. Braille is a simplified version of “night writing” – a code of raised dots developed during the Napoleonic wars to communicate combat messages so soldiers couldn’t be detected and killed while using lights on the battlefield. Braille’s system has allowed visually impaired people worldwide to maintain the independence and intimacy of the written word.

Think about your surroundings

You can offer visually impaired students so many other practical things. Wearing a digital voice recorder around your neck during lectures and in seminars has proved useful for hearing- and sight-impaired students alike. It also allows lecturers to move freely as they teach.

Offer to meet your sight-impaired student before the seminars begin and discuss lighting and where they would like to sit. If they have a guide dog, give both the student and the dog plenty of space, and make sure that the other students don’t distract the dog.

Help your student to understand and navigate the layout of the room and how they might want to deliver presentations. Ensure that they can enter the lecture theatre first and leave safely afterwards. Another student may be able to go in with them to guide them to their chosen seat.

Take them to your office location, so they can access support during your office hours if they wish. If they have a mentor, library assistant or note-taker, include them in your plans and copy them into emails if the student agrees.

Engage with student services to put reasonable adjustments in place

For UK-based educators, the first question to ask when you become aware of a student’s visual disability is: have they had an assessment as part of the DSA? If the answer is “yes”, then they will be able to share with you as many of the recommendations as they feel comfortable disclosing.

If they have yet to have this assessment, sending them to student services to begin this process of assessment is a priority. Reasonable adjustments create an environment in which students with special educational needs or disabilities have an equal opportunity to display their intelligence, accomplishments and understanding. This could be extra time allowances for written assessments and exams, providing large-print or Braille hard copies of handouts and course information or having a CCTV or video magnifier in the seminar room.

If a student requires a Braille hard copy, these are produced using a Braille embosser and transcription software. Student services will give you all the information you need so you can implement these adjustments or put you in touch with the relevant reprographics staff. International students are not eligible for the DSA. A number of UK scholarships and financial assistance schemes are available for international students with disabilities and special educational needs; approaching the relevant student well-being service is the first step.

Kate Armond has taught literature and international modernism at the University of East Anglia and the University of Essex. She is now senior lecturer in literature and critical theory.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.