“It is a sobering tale, the rise and fall of both Marys,” says Charlotte Gordon towards the end of this gripping dual biography of the mother and daughter whose lives so briefly crossed. Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), died a mere 10 days after giving birth to Mary Godwin, author of Frankenstein (1818), but the first Mary’s impact on her daughter’s life choices was immeasurable. The “sobering” element comes from the frustrations of their “outlaw” status in a disapproving society. Men used and rejected them, their close relations killed themselves, their children died, and their books were panned by the critics of the day. Even after death, their reputations took a further battering. Wollstonecraft’s devoted husband, the philosopher William Godwin, in dashing off a frank memoir, inadvertently ensured that his wife’s contribution to feminism would be ignored for another century. In dwelling on her love affairs, he made her into a notorious “fallen woman” and discredited her value as an Enlightenment philosopher.

The facts of their lives are well known, but what makes this biography so riveting is its doubling of the two Marys in alternate chapters, deepening the reader’s immersion in the fabric of each woman’s struggle before plunging back into the parallel story. The effect is not just to trigger comparisons, but to overturn chronologies, and to make us follow two disastrous histories simultaneously.

Had they lived to compare experiences, mother and daughter would have had plenty to discuss: first the troubled childhoods, then the moody adolescence, followed by the frustrations of thwarted sexuality. Infatuated first with young women, they transferred their affections to philandering men who abandoned or exploited them. Sisters multiplied, demanding help. While the second Mary’s half-sister Fanny took an overdose of laudanum in a Swansea pub, her stepsister Claire Clairmont tagged along when she eloped with Shelley. A natural survivor in this tale of doomed youth, Claire withstood all subsequent regroupings and outlived them all.

Indeed, in Gordon’s account, the women seem more radical than the men, reading philosophy and learning Greek while sacrificing their reputations and trailing fragile babies around Europe. The travel details alone make for sobering reading, from the Shelley-Godwin elopement in unbearable heat, to the last gloomy house on the Gulf of Spezia where Shelley – who never learned to swim despite his passion for sailing – afterwards drowned in an unseaworthy schooner designed to outperform Lord Byron’s.

The most striking aspect of Mary Shelley’s story is that until she was widowed she was almost never alone. Her life with Shelley was shared with all kinds of hangers-on, from the entire Leigh Hunt family to a Greek prince who showed up when the family were encamped in Pisa. As babies sickened and died, Mary turned inward, withdrawing from Shelley who essentially did what he liked, whether sitting naked on a wet rock reading Greek or concocting his favourite snack of mashed bread and sugar. Wollstonecraft was lonelier. She was in her thirties before she had any real sexual experience, but her life mellowed while her daughter’s soured.

The strength of this compelling biography, which skims lightly over the books to focus on the lives, is its ability to convey what it felt like to be a woman full of thwarted hope and ambition, so that we experience every personal blow, every tragic loss, from each Mary’s bruised perspective. Even after Shelley’s death, on two occasions a new suitor would offer himself to the widowed Mary, only to sneak off and marry someone else. Were they just too needy, and the Wollstonecraft ideal belied by its emotionalism? The resilience of mother and daughter in keeping going when no one seemed to understand them makes this remarkable story of two feminist icons all the more vivid and moving.

Valerie Sanders is professor of English and director of the Graduate School at the University of Hull. Her most recent publication is a scholarly edition of Margaret Oliphant’s novel Hester (2015).

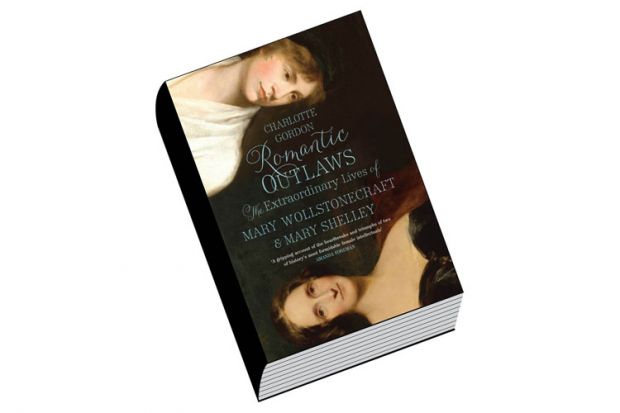

Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley

By Charlotte Gordon

Random House, 672pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780091958947

Published 29 April 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?