The compilation of a comprehensive anthology of premodern Chinese literature is a Herculean task few scholars attempt. While several major anthologies of Chinese poetry have appeared during the past three decades, readers seeking a broader representation of the Chinese literary world have until recently had to turn to Cyril Birch's Anthology of Chinese Literature (1965), an excellent, though now ageing, work, whose contents stop at the 14th century. The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature (1994), which draws together works by a number of eminent translators, provided a welcome and conceptually innovative breakthrough. Stephen Owen's new Anthology of Chinese Literature, with translations almost exclusively by Owen, offers a still more radical and exciting approach that will give further inspiration to students and general readers trying to make sense of the sometimes bewildering span of Chinese literary achievement.

The traditional approach to the compilation of such an anthology has been to arrange the chosen material along straight chronological lines. Such a sense of chronology is crucial, because the development of genres must be understood in terms of their historical grounding and because, as Owen points outs, in traditional China "the reader's awareness of the (historical) period of which he or she was reading was an important part of the reading experience". Moreover, at a more practical level such a layout seems essential if the general reader is not to become lost.

The danger with the straight chronological approach, however, is that it presents too baldly compartmentalised a view of development, and fails to suggest the unitary nature of the Chinese literary tradition, a tradition whose constituent works "(cut) across chronological history with ease" and in which "a poem from a thousand years in the past might not be essentially different from a poem written yesterday". Thus for Owen, an anthology must "accomplish the critically important task of recreating the family of texts and voices that make up a 'tradition' rather than simply collecting some of the more famous texts and arranging them in chronological order".

Considering the difficulty of this task, Owen's approach is remarkably successful. While the basic layout follows broad chronological units (introduced by excellent historical overviews), within each of these there is sometimes considerable freedom of organisation. Often, Owen's subdivisions follow genre developments (the unit on "The Chinese Middle Ages", for example, begins with subdivisions on "Yue-fu", and on early shi poetry); but he is equally happy to switch to other, for example, thematic, preoccupations (the same unit continues with a subdivision entitled simply "Feast"). Within each subdivision, there is an attempt to forge cross-dynastic and cross-generic links. This is done most frequently by the interspersing of pieces clearly labelled "other voices in the tradition", while elsewhere pieces from outside the main chronological unit are introduced in a more unmarked fashion. Though readers used to traditional anthologies may find this intertextual criss-crossing a little confusing or over-intricate at times, it is worth getting accustomed to such groupings: their boldness is founded on sound literary judgement.

Only occasionally does one feel an element of the tradition might have been more clearly presented. The genre of fu ("poetic expositions") could have benefited from a separate, or a more overt, discussion. The scope of fu included, though not large, is certainly as wide as the constraints of the anthology will allow. But the majority are subsumed under "The Chu-ci tradition"; though this linkage is well made, there is very little to signpost that these pieces form part of their own major and distinctive genre group.

The commentary that guides us through the individual strands of the tradition is one of this anthology's greatest strengths. The Classic of Poetry, for instance, is a highly complex collection encompassing different historical, thematic and interpretive perspectives. Owen's numerous examples of its poems are arranged, with commentary, in such a way as to reveal these differing aspects one by one: first, chronological and thematic divisions are pointed up, then the later Confucian interpretive stance is introduced, and finally attention is drawn to traditional theoretical features such as bi and xing that become central to subsequent poetic theory.

All this makes for a work that really imparts a sense of literary history and succeeds brilliantly in highlighting important compositional features, while always keeping the texts to the fore.

In the translations, Owen's guiding principle is that his texts read naturally in English: "To solve the numerous problems of translation from the Chinese, western scholars and translators have created their own special dialect of English. While some of the strangeness of this language is unavoidable, much of it is the deadwood of habit that contributes unnecessarily to the sense of the categorical strangeness of traditional Chinese literature."

Owen does much to prune out this "deadwood", proposing sensible new alternatives in a detailed note on translation. Reading his work, one is struck by just how conditioned we have become to seeing "jiu" universally translated as "wine", "qin" as "lute", and "hu" as "barbarian" - for these three examples, Owen suggests, we might also read "beer", "harp" and "Turks". Not that Owen is creating a rigid new "dialect" of his own. On the contrary, he approaches his texts with a refreshing flexibility that reflects a long-held belief that one's choice of words should depend on context. It is an approach he has elsewhere characterised more theoretically as a preference for "taking into account the functional modification of a word's semes" as against "retreat(ing) to a normative gloss or etymon".

An acute sensitivity to such fine nuances runs throughout this anthology, whether in the translations of Tang poems for which Owen is best-known), his Classic of Poetry selections, which are some of the most invigorating and accessible versions of that notoriously difficult text since Waley, or in his introduction of Americanisms ("shoot craps" and so on) to suggest vernacular language. One can, of course, carp over some usages, generally where one feels an attempt to suggest Chinese syntax might have been better avoided: the omission of the definite article in lines such as "whose swollen waters stretched to sky's edge" simply sounds awkward; likewise the substitution of a verb with a simple comma in a Mencian dialogue: "The king, 'It did'. Mencius, 'A heart such as this I'." But these are mere quibbles of personal preference.

In all, Owen's innovative anthology is one of the most stimulating general works on Chinese literature to have appeared for some time. It will set a standard subsequent anthologists will find hard to better.

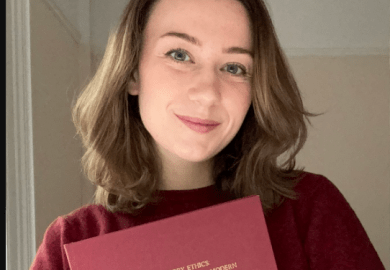

Robert Neather is Osaka Gakuin research fellow, Queens' College, Cambridge.

Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911

Editor - Stephen Owen

ISBN - 0 393 03823 8

Publisher - W. W. Norton

Price - £25.00

Pages - 1,212

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?