I have been talking to people recently about the revival of a ministry of reconstruction, necessitated by the dire situation facing the UK, and the need for a long-term view for its renewal.

That is not my alternative to a people’s vote on Brexit – it’s the story of 1917, when the leader of the wartime coalition government, Lloyd George, established the ministry of reconstruction to oversee rebuilding “the national life on a better and more durable foundation”.

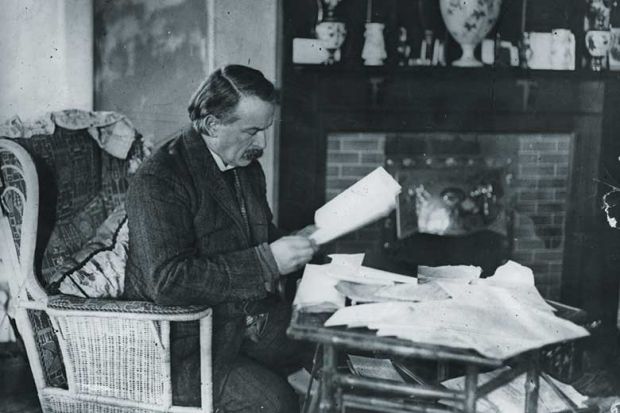

Its adult education committee — chaired by A. L. Smith, master of Balliol College, Oxford – published its Final Report on Adult Education in November 1919. That report set the groundwork for British adult education during the 20th century. Among other things, it recommended that all universities create departments for continuing education. Almost all responded positively.

The past 30 years of what the late economist Andrew Glyn described as “capitalism unleashed” created growing inequality of income and wealth, with “soft touch” regulation fostering the unsustainable speculative bubble that crashed in the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, followed by the first global recession in 2009 since the 1930s, and the subsequent decade lost in austerity.

This took its toll on the provision of adult education. The last Labour government undermined adult education by withdrawing funds from students who already had a qualification at the level they were studying – despite the rhetoric around flexibility and reskilling, which almost by definition requires the sort of education from which funding was withdrawn.

The subsequent coalition government did huge damage to adult education by tripling fees. For young people going to university, whether that is paid for through taxation or through a loan repaid by taxation is not necessarily going to change behaviour. For an adult wondering whether to take a course, and told that to do so they will need to take a loan that they will need to start repaying almost as soon as the course is completed, it’s a different story. That feels like a loan to replace the car or take a holiday. The effect on adult education was predictably disastrous. Predicted by everyone except David Willetts, the education minister who imposed it, who has had the decency to admit that he was wrong and that it was his biggest regret.

The Conservative government’s austerity has depressed still further exactly the sort of investment in adult education that society needs, for recovery and renewal, including for those areas left behind.

So, this has not been a party political issue. All three have failed in government. Yet all three claim to understand that lifelong learning is becoming increasingly important – with longer lives, including years in healthy retirement; with machine learning and robotics requiring a broad-based education for a population and workforce able to think imaginatively and laterally, with empathy and innovatively, as AI does the rest.

How to bring about the necessary investment?

A detailed plan was set out in the 1919 report and it was implemented, to good effect, over the next 70 years or so. We need to repeat that exercise. That task is being undertaken by the newly formed Centenary Commission, put together by the Workers’ Educational Association, the Co-operative College, the Raymond Williams Foundation and the universities of Nottingham and Oxford. As with the committee that wrote the 1919 Report, the Centenary Commission is being chaired by the Balliol Master, Dame Helen Ghosh, who hosts the inaugural meeting today (10 January).

The 1919 Report on Adult Education argued that a population educated throughout life was vital for the future of the country. What is striking is that they saw a series of challenges eerily similar to those we face today:

i. With the extension of the electorate, it was considered vital that citizens be made able to weigh evidence and critically reflect on political claims, so as not to be taken in by populist demagogues. Electoral issues are just as complex today.

ii. With the approach of new technologies and industries, skills training was considered insufficient, and instead people would need to be imaginative and flexible at work. With machine learning and robotics replacing routine work, these needs are even greater today, and growing over time.

iii. The population faced great challenges, foremost to prevent another slide into war. Many challenges today require concerted social and political action, of which climate change is perhaps the most pressing.

The aim is to publish a Report on Adult Education in November 2019, a century after the previous Report. It worked before. For all our sakes, we need to ensure that it works again.

Jonathan Michie is a member of the Centenary Commission, professor of innovation and knowledge exchange at the University of Oxford and director of the university’s department for continuing education.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Century-old plan for adult education must be revived

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?