If universities want to deliver the most valuable service and experience possible, they need to do more than simply prepare students for the workplace. Universities exist to encourage students to create positive change and disrupt industries – not just find work in them. Students should be offered the opportunity to think critically and independently and to question the status quo. Universities have a responsibility to help students consider their position and potential within society, both while in education and beyond.

How to achieve this in practice is obviously no easy task, but recognition of this fundamental aim can help galvanise and inform a university’s delivery of everything from building curricula, staff hiring, marketing to prospective students, events programmes and more.

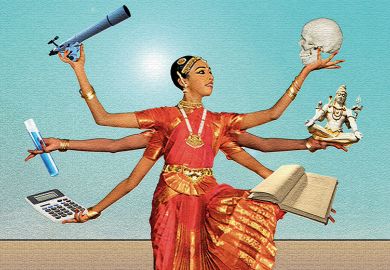

One of the most effective methods is to ensure an even balance between the teaching of technical skills and the soft skills that are key to helping students ask bigger questions and find solutions to increasingly complex challenges: creativity, problem-solving, empathy, communication, teamwork and storytelling.

Deloitte Access Economics forecasts that soft skill-intensive occupations will account for two-thirds of all jobs by 2030, compared to half of all jobs in 2000. And the number of jobs in soft skill-intensive occupations is expected to grow at 2.5 times the rate of jobs in other occupations. Soft skills prepare students for a world in flux, responding with innovative ideas and solutions so that industries – and society – can change for the better.

Despite the misleading title, soft skills actually create resilience in industries that are very often anything but stable. A teaching methodology that promotes a non-specialised and open-minded approach, where students can collaborate across courses and disciplines, can provide a view of the bigger picture. In addition, it can allow students to better adapt to future challenges, such as automation and precarious work. The desirability of such skills is reflected in the hiring practices of companies such as Google; many of the top characteristics that it measures potential leaders against are in fact soft skills. In addition, a recent study by LinkedIn reveals that 57 per cent of senior leaders value soft skills as more important than hard skills, emphasising their importance to the labour market.

Universities also have the task of future gazing to predict the type of thinking and skills that will enable today’s students to become the game changers of tomorrow. At the London College of Communication, UAL, we respond to changes in technology and society and ensure our students are up to speed through a curriculum that is always evolving. We have seen exciting developments in new courses, from the recent launch of our new MA in virtual reality, to courses in data journalism or design for social innovation and sustainable futures. We liaise with industry when planning which emerging areas to focus on so students can learn these skills, and how we should teach them.

As well as equipping students with future-proof soft skills and enabling them to think critically, creatively and responsibly, it’s essential that universities ensure students can put these into practice while studying. Our students don’t just learn about being the leaders, innovators and disruptors of tomorrow, or theorise how they might make an impact. They get involved with paid industry briefs and live projects. Through these experiences businesses recognise the qualities that students bring and students are allowed to refine their skills in a way in which failure is part of the learning experience.

In the midst of uncertain political and economic times, it’s perhaps tempting for universities to focus only on delivering the essentials. But by doing so, wider opportunities could be missed. Helping students take their first steps into their chosen field is of course important, but even more impactful is the idea that they can be encouraged to develop the capacity to create change for the better rather than simply “find a job”. All of society benefits from innovative and disruptive change, not just students and universities.

Natalie Brett is head of London College of Communication and pro vice-chancellor of the University of the Arts London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?