There is a diversity crisis in higher education.

Despite initiatives to improve the ethnic balance of the leadership in the UK’s education sector, progress continues to stall.

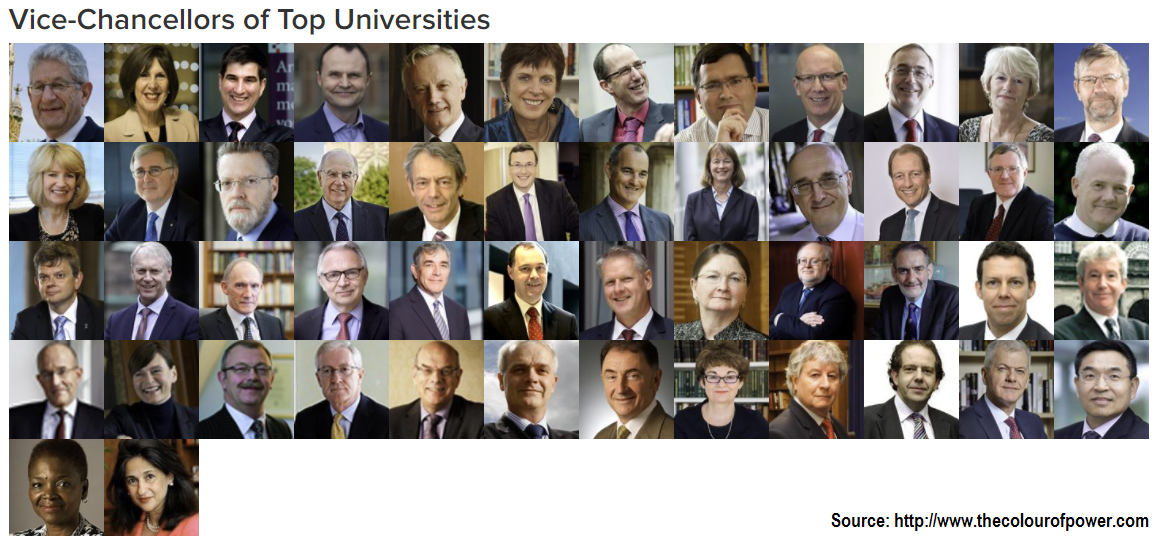

Given the international spread of the students, if university management is to truly understand their issues, should they not be representative of a wider ethnocultural base? Analysis by Green Park and Operation Black Vote (OBV) reveals that 94 per cent of the vice-chancellors of the UK’s top 50 universities are white, with just 6 per cent from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds.

Higher education’s leading establishments in the Russell Group have an ethnocultural representation that is 97.6 per cent white among the senior leadership, making it less diverse than boards of FTSE 100 companies.

Kofi Annan, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize and former secretary general of the United Nations, famously said: “Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family” – and yet UK academia is failing to achieve this because of structural inequalities in the management regime.

It is troubling that from one of the earliest exposures to hierarchy outside parenting, education, future generations are growing up seeing senior officials from mostly just one race. Education has always been held up as the archetypal solution to break down prejudice and barriers, yet our leading institutions are failing to set an example with the composition of their senior leadership.

Cultural diversity in the higher education sector has never been more important, socially or economically, in 21st-century Britain. If we are to attract students of diversity and ambition, we need to reflect those same characteristics in the leadership and professional services that deliver the student experience. This will result in a societal benefit in the recruitment, employment and entrepreneurship of a greater range of diverse leaders in the public, private and third sectors. It will also influence all levels of the employment spectrum and inspire students to be the best that they can be.

Educational establishments must be open and accountable, making top-down, public and transparent commitments to change and placing people in charge of delivering this, including the senate and wider executive leadership. Yet we know from the publicly available auditing of the ethnocultural composition of university management that they are failing. Senates urgently need to implement recruitment, succession planning and employee retention strategies that address the need for greater BAME representation at a senior management level.

Diversity strategies should not be a bolt-on to a university’s HR programme. Such programmes must be fundamentally reappraised to ensure that diversity is at the heart of these policies. Institutions need to create their own talent maps to ensure that they have a diverse leadership pipeline. If the existing talent pool is insufficiently populated with people with a diversity of backgrounds and experiences, universities should task experienced recruiters who can identify, engage and attract candidates from a wider ethnocultural base.

Drawing on experienced, external consultants can be an effective strategy to break through institutionalised barriers. Doing so often helps to cut through an issue that in-house recruiters struggle with, as they often present a panel of candidates for review that they believe an executive will “want to see”.

It is not just attracting talent that is an issue. Those employees with an ethnic minority background who are recruited by an organisation face additional barriers in reaching the top. Studies have shown that there is endemic subtle discrimination and “affinity bias” that minorities face as a matter of course in their careers.

People often favour, sometimes unconsciously, those in their own image, which means that we see a perpetuation of majority white, male leadership groups. As Raj Tulsian, chief executive of Green Park, said, leadership in the UK is “still statistically and behaviourally dominated by men of similar cultural and educational backgrounds”.

Conversations regarding race and difference may be difficult and contentious, but they cannot be ignored. Read any university literature and you will be bombarded with the words “inclusion”, “equality”, “diversity”, “dignity” and “respect”. The problem is, this language becomes a comfort blanket. Policies are in place at a student level, but the reality is that the administration doesn’t reflect this.

In higher education, the diversity of the student body often leads people to believe that the culture is supportive and inclusive, and this can translate into a mistaken belief that there is equality of opportunity among the faculty and administration.

If the issue isn’t addressed, given the activist nature of the student population, universities may see an absence of diversity in leadership having a tangible detrimental impact on recruitment both domestically and internationally. Students will vote with their feet if they don’t see equality of opportunity among the management of universities.

Universities should be facilitators of social mobility – they are currently failing in this task and need to be held accountable.

Geoff Thompson is chair of governors at the University of East London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?