Higher education in the UK has faced a blizzard of negative news over the past year or two. It has been exasperating to see universities’ incredible work and achievements eclipsed by endless stories about executive pay, supposed attempts to curtail free speech, and questions about value for money.

At the same time, a narrative has played out within the sector that has added to the sense of crisis: the battle over pensions in particular reopening wounds that are not easily healed.

The result is that it has been easy – far too easy – for universities to be cast as part of the problem rather than a solution to help address the sense of unease and unravelling that is gripping the country. How has this happened, and what can universities do to get back on track?

The question will be asked – and answered – at a must-attend event this autumn, THE Live, where some of the sector’s brightest communicators and thinkers will gather to find a way forward. The two-day conference will culminate with the THE Awards, giving you two great reasons to join us.

As we launch the event, here are 10 ways that universities might consider changing the story:

1. Remember why you do what you do

Universities have attributes that many commercial organisations would kill for; values, authenticity and integrity cannot be bought, nor can a workforce that really is in it for love more than money.

And yet at times they can appear unaware how powerful these attributes are and instead they scramble to be poor imitations of the commercial sector. Sure, the marketisation of higher education under the English tuition fees regime – and the fierce battle to recruit students in particular – is largely the cause. But external factors can’t shoulder all the blame.

Leadership, culture and self-respect all matter, too. Universities’ primary missions are teaching and research, with social and economic impact spinning out from that. Focus relentlessly on excelling in these areas, and the metrics, league tables, marketing strategies and awards will follow. And if they don’t – well, it’s still the right thing to do.

2. Stop the civil war

One of the most damaging trends for UK higher education has been the breakdown in internal university relations, the sense of “them and us” that has solidified since the pension strike.

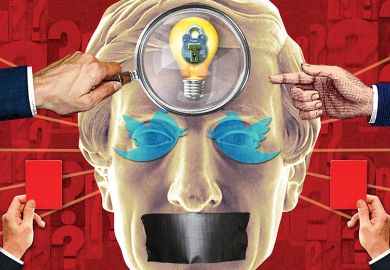

It has created a poisonous debate on social media in particular, in which grievances are raised in the most toxic and personal terms. Many of the concerns that fuel this atmosphere are legitimate – the casualisation of the academic workforce is a case in point.

But the spite and abuse that has spewed forth on Twitter and elsewhere has been unedifying, to say the least. It has to stop. Replace it with a sense of collegiality and mutual endeavour, and that will be a big step along the road to higher education regaining control of its own narrative.

3. Demystify, demystify, demystify

I am not sure if universities realise this or not, but for those on the outside, they are very opaque organisations. What do they do? Who do they do it for? And how am I benefiting? It is why the outdated idea of an ivory tower, an out-of-touch intellectual elite, is still a canard that quacks.

The structural complexity and sense that universities are for someone else is often demolished when you talk in specifics. Chat to the proverbial taxi driver in any university town and there’s every chance that they’ll parrot the usual tropes about higher education being a waste of money, too many people going to university and academics studying silly things with no bearing on reality.

Talk to them about their local institution, though, and they may well tell you about a family member who works there, the help a friend got from a university business clinic, how much they enjoy its museums, or their pride in a son or daughter who is studying there. Bringing this local understanding into the national narrative, and connecting the real with the mysterious, is a trump card.

4. Don’t obscure the good work with fripperies

A vice-chancellor turned up at THE’s office the other day with an entourage of zero, carrying his own bag (a rucksack) and travelling by the novel means of his own two feet. It was a sight to behold.

I am being a bit mean – the truth is we are already in the dying days of excessively grand v-cs, partly the result of generational change, partly the aftershocks of the pay scandal. Whatever the reason, it is not a moment too soon. There are always ways to rationalise chauffeur-driven cars and large grace and favour homes, but to be blunt, they make you seem not normal. Do you need them?

5. Don’t be a troll

People who work in universities should be available, open and influential, and social media seems – or seemed a few years ago – to be the ideal way to achieve those things. But you could also make a case that it has served up a self-indulgent, polarising mirage (see Point 2). A few thoughts: Do not waste time being rude to people you disagree with on Twitter. Anonymous troll accounts are not clever. The echo chamber exists. There is an opportunity cost to spending hour after hour on social media.

6. Don’t be an ostrich

Facing up to a problem is sometimes uncomfortable. But it’s never not a good idea. The most significant blow dealt to universities’ good name in the past couple of years was the opprobrium heaped upon them over executive pay. And a significant compounding factor was the silence echoing back, as vice-chancellors chose en masse to put their heads in the sand.

I understand their reasons: they felt there was nothing they could say that would mollify their accusers, that it was not their place to respond when their pay was set by others, and they probably felt scared about putting their head over the parapet. But the row could have been defused much earlier with recognition that this wasn’t going to blow over as it had in the past, and with some proportionate responses from those with the most inflated pay packets.

A reasonable pay cut and a donation of questionable bonus payments to a student hardship fund could have spared individuals and institutions from serious reputational damage. Similarly, it is a mistake to dismiss all concerns as wilful nonsense – grade inflation deserves serious investigation, so blanket denials are not the right response.

7. Do tell stories

And make them stories that real people will connect with. Universities seem obsessed with economic impact reports. The data are always compelling, and it may well be that this evidence is useful in bolstering the case for funding in particular. But has an economic impact report ever really changed anyone’s mind about anything?

By contrast, I was in a university lab a while ago when I was shown a lump of plastic. It was a reproduction of a child’s heart, I was told. The university had teamed up with surgeons in a local hospital heart unit where a child lay in desperate need of an operation. The surgeons were not sure what they were facing and wanted to know exactly what the situation would be when they got in. There was no room for mistakes.

By scanning the heart and 3D-printing a replica, they were able to cut cross sections through the model and understand precisely what the problem was. The operation was a success. That is a story about impact that is worth telling.

8. Value people, not buildings

I have lost track of the number of times I have been shown an expensive new building while visiting a university. I understand why – institutions spend tens of millions on them, and they are often impressive. Indeed, universities kept the construction industry in much of the country solvent after the financial crash (see above re economic impact reports).

But don’t be fooled: it is people who really matter. Show us people, not stuff. Invest in people. They are the ones who will persuade the world about the value of what you do.

9. Accept that the world is changing – and that’s OK

Our higher education system in the UK is one of the world’s best. No doubt about it. But, whisper it, there’s also a sense when you travel around the world that the UK is too wrapped up in itself and not as outward-looking as it should be. Others are innovating more rapidly in some key areas, and are facing up to the challenges that the world, politics and technology are throwing at us.

Come back to the UK from a trip to Asia, and the debates that circulate and recirculate, the obsession in the national media with Oxbridge, fees and not much else, can seem stale and parochial. Let’s be proud of our national sector – but let’s not stagnate. Trying new things is rarely as bad as the naysayers would have you believe.

10. Join us at THE Live this autumn

Universities are one of the wonders of the world. Working in them – breaking new ground in research or helping to guide young minds that will shape the world tomorrow – should be a joy.

That it isn’t for many in academia tells us that something has gone wrong. But it can be put right. Higher education needs to rekindle that sense of optimism and enthusiasm and find a way to change the story. Join us on 27-28 November in London to be part of something important.

John Gill is editor of Times Higher Education.

THE Live will take place in London on 27-28 November 2019. Find more details as well as information on how to secure your early-bird places here.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?