Research networks and innovation: fostering cross-boundary collaboration and interdisciplinarity in science

Sponsored by

Sponsored by

Collaboration is essential in science. Scientists from multiple disciplinary fields and stakeholders from diverse institutional environments and social communities are working together increasingly. In recent years, interdisciplinary, cross-institutional and transdisciplinary approaches in science have been highlighted as pivotal to achieving breakthrough discoveries, addressing societal challenges and promoting innovation. These collaborations bring together complementary expertise and plural perspectives, triggering a fruitful dialogue on what is worth investigating, how and why.

However, although interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity hold great promise for the generation and application of knowledge, collaboration is not always straightforward. Mobilizing knowledge and resources in research collaborations to advance science and innovation can be challenging. Different disciplines and/or institutional settings use different cognitive frames and respond to distinct logics, norms and incentives and these differences can reduce the opportunities for knowledge sharing and exchange, undermining the capacity of collaborations to fulfil initial expectations.

Pablo D’Este and Adrián A. Díaz-Faes from INGENIO, a joint research institute of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV), and Óscar Llopis from the University of Valencia (UV) are working together as a group to address the problems associated with interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research collaborations. They are using primary and secondary data on research collaborations gathered through fieldwork and large-scale surveys, combined with data on science and innovation outputs. The group is using social network analysis techniques and multivariate statistical methods to examine the relationships between scientists’ research networks, knowledge generation and behaviours. The objective is to better understand how knowledge (and other tangible and intangible resources) can be mobilised more effectively in research collaboration contexts that include scientists and stakeholders from a range of disciplines, areas of expertise and institutional settings or social communities.

This research programme is focusing on biomedicine as the main context of analysis. The biomedical research setting provides a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between research networks and innovation. Biomedical research networks include a diverse range of actors such as basic and clinical scientists, patients, medical practitioners and policymakers whose common goal is to advance medical innovation and healthcare. The environments of these actors span universities, hospitals, patient associations and industry (among others) and recombining their know-how to improve healthcare is complex and challenging since it involves crossing organizational, institutional and professional boundaries. Although it has been recognised explicitly that surmounting these barriers is crucial, little is known about the factors that facilitate the mobilisation of knowledge to achieve innovation in highly heterogeneous networks. This open question constitutes the empirical and policy background to our research.

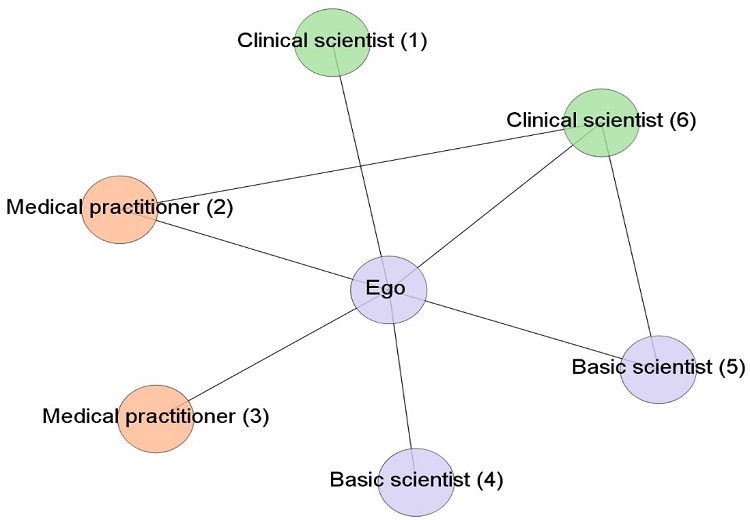

The research group’s most important recent findings are summarised next. First, it provides evidence of the positive influence of the open structure and diverse composition of scientists’ networks on medical innovation (1) (2). Scientists in intermediary positions between otherwise disconnected actors or between actors from different institutional settings are better able to exploit and apply the knowledge opportunities arising from translational research. Results show that some intermediary roles (i.e., gatekeepers and consultants, see Figure) are more effective than others (2). The group’s research shows also that, compared to men in similar research contexts, women scientists establish more diverse research networks and more frequently assume intermediary roles between actors from different institutional settings (3).

Second, it has been shown that in order to transform the knowledge and resources potentially available through research networks into innovation, scientists need an explicit strategic collaborative approach to networking. This pro-collaborative networking strategy creates more opportunities for cooperation, enables dialogue among actors from different disciplines, reduces opportunistic behaviours and helps to balance conflicting priorities of network participants (1).

Third, scientists who interact closely with end-beneficiaries (i.e., patients, patient representatives) are more likely to engage in innovation activities. This relationship is particularly strong if interactions with end-beneficiaries occur in research settings more distant from the context of application (e.g., basic research vs clinical settings) (4).

Fourth, this stream of research has highlighted the importance of increasing awareness of the connection between research practices and network’s content - i.e. the specific types of resources that can be mobilised in research collaborations. Focus on network content provides a new methodological lens to assess policy initiatives oriented to fostering translational research on a process rather than an outcome perspective (5). Findings show that mobilising intangible resources (e.g., multiple forms of scientific legitimacy) can favour the participation of scientists in practices related to innovation and societal impact (6).

Fifth, results show that scientists involved in interdisciplinary research are more likely to generate scientific findings with high societal visibility (i.e., research findings that attract the attention of non-academic audiences), measured by mentions to scientific articles in blogs, news media and policy documents (7). This line of research has also evidenced an interplay between interdisciplinary research and collaboration with non-academic actors. On the one hand, showing that interdisciplinarity is often an antecedent to various forms of collaboration with non-academic actors (8); on the other hand, revealing that the positive association between interdisciplinarity and societal visibility is particularly strong among scientists who collaborate with actors outside academia (7).

In sum, research collaborations that employ interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches are crucial for science aimed at advancing fundamental understanding and responding to societal challenges. This research programme’s objective is to provide a better understanding of the factors that enable and hinder these research collaborations in order to unleash their potential for scientific discoveries and innovation.

This Figure depicts the network of a basic scientist (the “ego”) and shows that an actor can occupy multiple brokerage roles. The total number of brokerage roles held by this scientist is 13, distributed as: Nº of coordinator roles = 1 (4-5); Nº of gatekeeper roles = 7 (1-4, 1-5, 2-4, 2-5, 3-4, 3-5, 4-6); Nº of consultant roles = 2 (1-6, 2-3); Nº of liaison roles = 3 (1-2, 1-3, 3-6). In the ‘coordinator’ role, all three actors belong to the same professional community; ‘gatekeeper’ corresponds to an open triad where the alters belong to different professional communities, one of which is the same as that of the ego; ‘consultant’ includes alters from the same professional community, which is different from that of the ego; and ‘liaison’, which is the most heterogeneous open triad, is where all three actors belong to different professional communities.

Further reading

(1) Llopis, O., D’Este, P., Díaz-Faes, A.A. (2021): “Connecting others: Does tertius iungens orientation shape the relationship between research networks and innovation?”, Research Policy 50(4): 104175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104175

(2) Llopis, O., D’Este, P. (2022): “Brokerage that works: Balanced triads and the brokerage roles that matter for innovation”, Journal of Product Innovation Management 39(4): 492-514. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12618

(3) Díaz-Faes, A. A., Otero-Hermida, P., Ozman, M., D’Este, P. (2020): “Do women in science form more diverse research networks than men? An analysis of Spanish biomedical scientists” PLoS ONE 15(8): e0238229. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238229

(4) Llopis, O., D’Este, P. (2016): “Beneficiary contact and innovation: The relationship between contact with patients and medical innovation under different institutional logics”, Research Policy 45 (8): 1512-1523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.03.004

(5) Díaz-Faes, A.A., Llopis, O., D’Este, P., Molas-Gallart, J. (2023): “Assessing the variety of collaborative practices in translational research: An analysis of scientists’ ego-networks”, Research Evaluation rvad003. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvad003

(6) Llopis, O., D’Este, P., McKelvey, M., Yegros, A. (2022): “Navigating multiple logics: Legitimacy and the quest for societal impact in science”, Technovation 110: 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102367

(7) D’Este P., Robinson-García, N. (2023): “Interdisciplinary research and the societal visibility of science: the advantages of spanning multiple and distant scientific fields”, Research Policy 52(2): 104609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104609

(8) D’Este, P., Llopis, O., Rentocchini, F., Yegros, A. (2019): “The relationship between interdisciplinarity and distinct modes of university-industry interaction”, Research Policy 48(9): 103799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.05.008