Re-engineering nature to fight antibiotic resistance

As antimicrobial resistance accelerates worldwide, researchers at Baku State University are exploring how nature-inspired chemistry can offer new solutions against drug-resistant infections.

Sponsored by

Sponsored by

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most urgent global health challenges of the 21st century. Infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), are becoming increasingly difficult to treat, while the global pipeline of new antibiotics continues to shrink. This widening gap between clinical need and pharmaceutical innovation demands alternative scientific strategies.

Researchers at Baku State University (BSU) are addressing this challenge through interdisciplinary academic research that combines organic chemistry, microbiology and computational modelling. In response to current global priorities in antimicrobial discovery, scientists at the university’s Industrial Chemistry Laboratory have synthesized a new series of bioactive compounds designed to combat resistant bacterial pathogens.

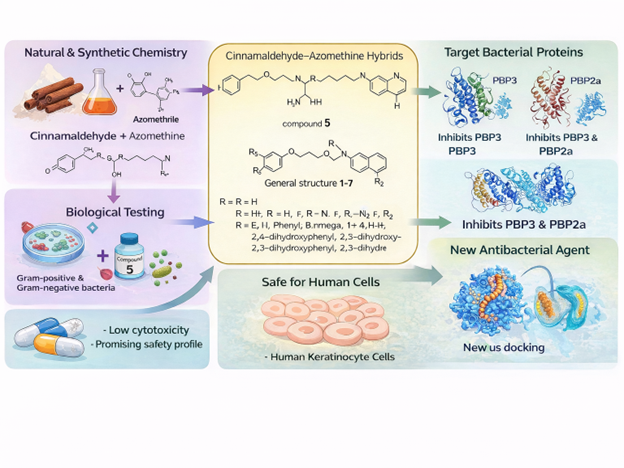

The research draws inspiration from cinnamaldehyde – a naturally occurring compound responsible for cinnamon’s characteristic aroma and long recognized for its antimicrobial properties. By integrating cinnamaldehyde with azomethine (Schiff base) structures, the BSU team created a novel family of hybrid molecules aimed at enhancing antibacterial effectiveness through modern medicinal chemistry techniques.

To evaluate their biological potential, colleagues from the Laboratory of Microbiology and Virology at BSU tested seven newly synthesized compounds against ESKAPE pathogens – a group of bacteria responsible for many hospital-acquired infections and known for their resistance to existing antibiotics. One compound emerged as a particularly strong candidate, demonstrating pronounced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, including clinical isolates.

Further microbiological investigations revealed that the compound does not merely suppress bacterial growth. Instead, it actively disrupts bacterial cell division and damages the cell wall, mechanisms that directly compromise bacterial survival. Such multi-target effects are considered especially valuable in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Equally important is safety at the early stages of drug development. Cytotoxicity tests conducted on human skin cells showed low toxicity at concentrations effective against bacteria, indicating a promising balance between antibacterial potency and biocompatibility.

Computational modelling provided additional insight into the compound’s mode of action. Simulations demonstrated that the lead molecule interacts with two critical bacterial proteins: PBP3, which plays a central role in cell wall synthesis, and PBP2a, the protein responsible for methicillin resistance in MRSA. By targeting these proteins, the compound addresses resistance mechanisms directly, rather than competing with existing antibiotics that bacteria have already learned to evade.

As many pharmaceutical companies reduce investment in antibiotic research due to high costs and limited commercial returns, universities are increasingly becoming key drivers of early-stage antimicrobial innovation. This work at Baku State University highlights the strategic importance of interdisciplinary research environments, where chemistry, microbiology and computational science converge to address global health priorities.

Although the findings remain at a preclinical stage, they illustrate a powerful and timely concept: future antibiotics may emerge not from entirely new chemical classes, but from the re-engineering of familiar natural molecules using advanced scientific tools. In the global race against antimicrobial resistance, higher education institutions have a critical role to play – not only in discovery, but in developing solutions that society urgently needs.