Listening to a story read aloud is a familiar experience to most of us. Whether it comes to us via a parent, a storyteller or a digital download, the spoken book enthrals the listener in many more ways than any neurological investigation is likely to uncover. Matthew Rubery describes his study as “an awkward conversation about recorded books”, which is unnecessarily apologetic, as it is the first comprehensive attempt to examine the 150-year phenomenon of audiobooks, from the earliest sound recordings in the late 19th century to text-to-speech software in the 21st.

The magnitude of this task becomes evident in Rubery’s introduction, as most of the terms he uses have to be defined. When is a reader a reader? Or should we say “narrator”? Are we reading a book when we listen to it? And above all, is “just listening” as valuable as “reading” a book?

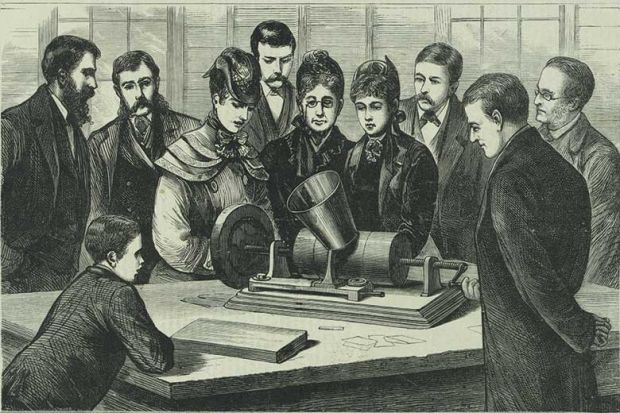

These themes recur throughout the three parts of Rubery’s study, which covers the development of recording and reproducing technologies, their acquisition and availability, and the issues arising from the publication and the consumption of these products. It is notable that the audiobook has always been associated with those unable to read, and in particular the blind and visually impaired. It was in serving this audience that “talking books” established themselves through the Library of Congress in the US and a number of charities in the UK. By the mid-1930s, there was a growing archive of titles available to the blind, many of whom were First World War veterans, and it expanded yet further in the 1940s with the advent of the “long player”, the vinyl record album. It became possible to produce full, unabridged readings of novels and other publications without having to stretch them over hundreds of discs, and the post-war economic boom enabled not just the visually impaired but also the general public to purchase (rather than borrow) talking books.

As Rubery discusses, the commercial availability of recorded books spurred rapid growth. Major publishers got in on the act, producing not only audio versions of modern classics but also Beat poetry and previously “unrecordable” material. While arguments raged about the validity of consuming culture in this form, a further technological advance, the cassette tape, turned the audiobook into a fully fledged mass medium, able to compete with radio in commuters’ cars and elsewhere.

As with previous technological revolutions, computer technology failed to bring about the downfall of the printed book; if anything, electronically published audiobooks, on CD or via download, increased book sales and created more opportunities to make literature accessible to all. The charge of “Kentucky Fried Literature” that was often thrown at talking books now rings rather hollow, although the debate rumbles on.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the world’s biggest bookseller, Amazon, is now the largest producer of audiobooks, via its subsidiary Audible. Whether in future we will be read to by humans or robots appears immaterial. What is certain is that we will continue to derive pleasure from it, and Rubery – who sees audiobooks as a distinctively modern art form – makes a convincing case for why we should.

René Wolf, formerly tutor in history, Royal Holloway University of London, runs the academic podcasting service Backdoorbroadcasting.net. He is author of The Undivided Sky: The Holocaust on East and West German Radio in the 1960s (2010).

The Untold Story of the Talking Book

By Matthew Rubery

Harvard University Press, 384pp, £20.00

ISBN 9780674545441

Published 24 November 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?