For me, as for many others at Cardiff University, the recent news coverage of Malcolm Anderson’s suicide has been a real blow. I did not know the accounting lecturer personally. The thing that was so shocking about reading the articles was just how familiar many of the details felt. I have heard numerous stories from colleagues who feel like they are barely holding on. People are struggling with unmanageable workloads and feel as though they are constantly failing.

These are people who have asked for help and have been told that their school’s hands are tied and that there is simply no way to ease their workload. Others have told me that they can’t go on any more. I am terrified that one day it will be one of my friends who won’t be able to cope any more.

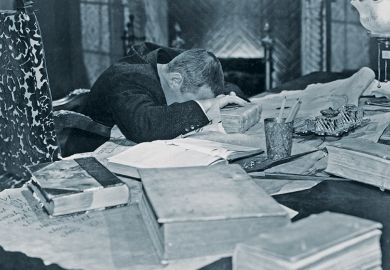

Cardiff University has promised to review mental health provision in the wake of Mr Anderson’s death. This is not only wholly inadequate, it is also dangerously misguided. While good mental health resources are important, the discussion that we need to have cannot only be about mental health. Framing the suffering experienced by staff and students as a mental health crisis obscures the material causes of this suffering. No amount of counselling will make you resilient enough to be able to mark 418 exams in 20 days without experiencing immense suffering.

Framing this discussion as one that is entirely about mental health implies that it is the individual who is failing and needs fixing. While mental health services can be life-saving, they ultimately shift responsibility from the institution to the individual.

Mindfulness, yoga and breathing exercises – all these different measures that are meant to help people deal with stress can be turned against them. Many people end up blaming themselves when they fail to engage with them. Many think that maybe they would have been able to handle their workload if only they’d done their breathing exercises more regularly.

For the past few months, Cardiff University has been offering staff the opportunity to take part in suicide prevention training, which is intended to teach staff how to spot risk factors. Such training is particularly insidious. Now, on top of our own struggles, we are supposed to keep each other alive. Now, if someone takes their own life, we can blame ourselves for not having seen the signs.

If we really want to tackle mental health issues in higher education and prevent suicides among staff and students, we have to change what is making us sick. This includes tackling the culture of chronic overwork caused by escalating student numbers that come without commensurate staffing increases, as well as fighting casualisation and working to alleviate financial insecurity. In the UK, 68 per cent of research staff at universities are now employed on fixed-term contracts and almost a third of all teaching is delivered by staff who are paid hourly.

With fees at £9,000 a year, students are under increased pressure, too. The current pensions dispute, which earlier this year led to the biggest strike that the UK higher education sector has ever seen, is further evidence of how academics’ working conditions are getting worse. If our pensions are switched from a defined benefits to a defined contributions scheme, thousands of younger staff will be left in pension poverty during retirement.

All these factors are inevitable consequences of universities being run like businesses. Cardiff University, like many institutions, arguably keeps its staff in a constant state of crisis through heavy workloads and casualised contracts. At the same time, it has several ambitious building projects that eat up millions of pounds.

If the university was going to change the way that it treats staff in light of this terrible story, it would already have started. Instead, at 5.30pm on Friday, less than 48 hours after news reports appeared suggesting that a staff member might have taken their own life because of an unmanageable workload, Cardiff University sent out emails informing staff members in the social sciences that their allocated workload for the next academic year was available for viewing. Staff also received a reminder on Saturday at 7am. If Cardiff University really is committed to increasing staff well-being, it will have to do better than this. Such emails tell us a lot about how committed the university is to improving staff well-being.

If we want to create a working environment that doesn’t make people sick, we will have to fight for it, and the only way that we can possibly win this fight is by organising. The University and College Union has recently said that fighting excessive workloads is one of its main priorities and, after the pensions strike earlier this year during which the UCU gained 16,000 new members, it feels as though this is a fight that could be winnable.

I would like to thank Steven Stanley and Jean Lennox for their support in writing this article.

Grace Krause is a research student in Cardiff University’s School of Social Sciences.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?