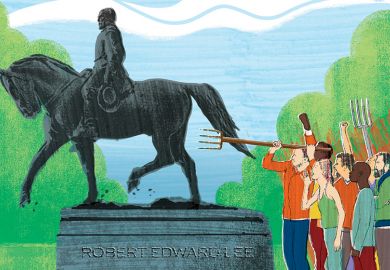

For the first time in more than 100 years, the sun rises in Chapel Hill without casting its light on Silent Sam, the memorial to a Confederate soldier that has long loomed over the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill campus. On 20 August a group of protesters toppled the statue and accomplished the goal of decades of anti-racist activism.

As a recent alumnus of UNC, I’m excited to see a future for the university where the virulent racism embodied by this statue isn’t allowed to continue to fester.

And as a former campus activist who spent a significant part of the last four years advocating for a more racially just UNC, this moment has been cathartic.

However, the reaction from UNC administrators and North Carolina elected officials has been less enthusiastic. They’ve accused protesters of abandoning a proud tradition of civic discourse and legal change in favour of aimless destruction. As condemnation of the statue’s removal spreads, it is important to understand that this conflict is as much about free expression and democratic movements on college campuses as it is about Confederate memorialisation.

The fight about Silent Sam started in 1965 when a student named Al Ribak wrote a letter to the editor of the Daily Tar Heel calling for the removal of the statue and sparking a campus-wide discussion.

Since then, generations of community organisers, student activists and committed faculty and staff members have repeatedly agitated for contextualisation or removal of the statue. Campaigners have suggested alternative monuments that could better represent the minority voices forgotten by historical memory at UNC.

Protesters have criticised the pro-slavery ideology that the Confederate soldier Silent Sam represents – and critiqued the early 20th-century white-supremacist thuggery that supported the statue being erected on campus. Local industrialist and Ku Klux Klan member Julian Carr’s notorious brag about “horsewhipp[ing] a negro wench” during his dedication speech for the statue exemplified this ideology.

The efforts to move Silent Sam have spanned decades and encompassed almost every conceivable form of civic discourse. But administrators and the majority of state legislators have ignored the opposition and attempted to silence the criticism.

Aggressive attempts to inhibit dissent to Silent Sam’s presence spiked when North Carolina passed a law in 2015 that prohibited taking down any statue on public property, including Confederate monuments.

That hostility then trickled down through the UNC system board of governors, which has spent the past half-decade ignoring constant student protests. In 2017 it passed a draconian free speech policy meant to enable harsh punishments for people involved in campus protests.

I got involved in advocating for the removal of Silent Sam through the Campus Y, a hub for social justice movements on UNC’s campus that has existed for more than 100 years. But many of the most important people leading the campaign to topple the statue represent newer organisations or speak outside of the strictures of organisational representation.

And support for moving the statue went beyond student groups. Many faculty departments wrote statements of support, as did the Schools of Education and Law. Chapel Hill’s house representative David Price backed the campaign, as well as state legislators Verla Insko and Valerie Foushee. The Chapel Hill-Carrboro Chamber of Commerce also supported the effort.

I’ve observed that the same language meant to vilify opponents to Silent Sam for all these years is now being used to decry the toppling of the statue. UNC’s chancellor, Carol Folt, described the protesters’ actions as “unlawful and dangerous”.

Meanwhile, UNC system president Margaret Spellings and UNC system board of governors chair Harry Smith issued a joint statement calling the action “unacceptable, dangerous and incomprehensible”. They went on to say that the statue’s removal represented a tendency towards “mob rule” that contradicted the country’s heritage as a “nation of laws”.

Former governor Pat McCrory compared the removal of the statue to Nazi book burnings, and the leader of the North Carolina senate Phil Berger referred to Monday evening as a “violent riot”.

Everyone at UNC, particularly white students and faculty members, has a responsibility to stand strong against any condemnation of the acts or the protesters by university leadership. They must continue to support anti-racist organisations at all levels. Promoting reform does not end at statements of support.

UNC has the chance to demonstrate to universities around the world what the beginnings of restorative justice might look like on campus. It took more than 50 years to tear down this one small emblem of UNC’s complicity in white supremacy, but it doesn’t have to take 50 more to get rid of the rest.

Alexander Peeples graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2018.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?