International observers of American higher education are frequently struck by its high and consistently rising tuition fee levels. Since government funding of American higher education is a bit convoluted by international standards, a little background is helpful.

The federal government mostly provides funding to students in the form of financial aid, rather than providing direct subsidies to universities. The federal funds that do go directly to universities tend to be tied to specific research projects. State and local (provincial) governments do provide direct subsidies to public but usually not private universities within their territories. In recent years, federal funding has increased, but state funding has fallen.

Many people argue that this fall in state funding is driving the tuition increases at public universities. The theory is quite solid. The costs to educate a student must be covered by the combination of state funding and tuition, so if state funding decreases, tuition needs to increase to make up the difference.

For instance, a recent State Higher Education Finance report documents that for fiscal year 2016, total revenues per student at public colleges was roughly $13,000, composed of about $7,000 in state funding and $6,000 in tuition revenue. If state funding falls by, say, $2,000 per student, then state funding would only be providing $5,000 of the $13,000 total, so tuition revenue would need to increase by $2,000 to $8,000. While this theory is on solid theoretical ground, it runs into two empirical problems.

First, over the past 26 years, average real state funding per student has fallen by $780, while tuition revenue has increased by more than $3,500. This means that cuts in state funding can only explain about 22 per cent of the increase in tuition over the past quarter century.

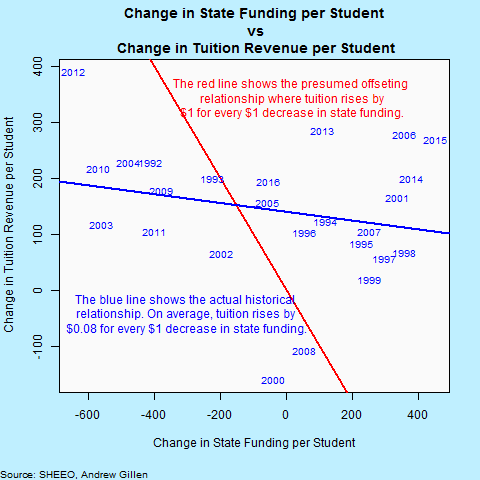

But there is a second empirical problem. If changes in tuition are driven by changes in state funding, then tuition should increase by more in years when state funding is cut then when it is not. In fact, there should be a $1 for $1 relationship. But when you plot tuition rises against changes in state funding, for every year since 1992, a $1 change in state funding per student is rarely associated with a $1 increase in tuition.

There are years when the prediction holds – for instance, in 1993, state funding was cut by $225 per student and tuition increased by $200. But the very next year, state funding increased by $117, meaning that tuition should have fallen by a similar amount. Instead, tuition increased by $122.

When looking at the past quarter century, on average, a $1 change in state funding is associated with only an $0.08 change in tuition. In addition, the data indicate that even if there were no change in state funding per student from one year to the next, we would still expect tuition to increase by $140 on average.

In sum, the idea that tuition increases because state funding has fallen is theoretically sound, but is not supported by the data. We’ll need to look elsewhere to find what’s behind rising tuition at American colleges.

Andrew Gillen is an independent higher education analyst in the United States.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?