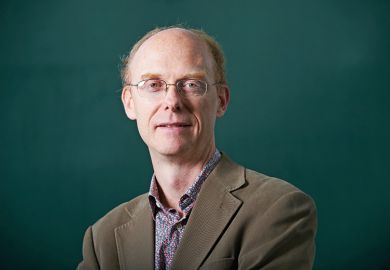

Adrian Kavanagh, a lecturer in geography at Maynooth University, is an expert on the Eurovision Song Contest. He specialises in the geography, history and voting politics of Eurovision song entries and supervises a final-year research group on the same topic. In March, he gave a lecture on Eurovision voting patterns at a Maynooth conference focusing on the contest. The final of this year’s competition will be held in Lisbon on 12 May.

Where and when were you born?

Portlaoise, in County Laois, in the Irish Midlands in 1970, missing out on the 1960s by a matter of days.

How has this shaped who you are?

It has definitely shaped my inability to pronounce my “th’s” correctly. Laois people and other Midlanders tend to be unpretentious, unassuming and not great at putting themselves forward, which does explain why I cannot network at academic conferences to save my life. Rural society in the Irish Midlands tends to be free of class divisions and this feeds into an anti-elitist slant in the way that I approach, and do, my job.

Why did you become interested in Eurovision as a research topic?

I’ve always been interested in the Eurovision Song Contest, but I am also fascinated by elections, maps and numbers, while I enjoy different forms of music, so Eurovision as a topic nicely cuts across all these different themes. But there’s a lot more to Eurovision academically than just the voting: research shows that certain countries can use the contest for the purposes of nation-branding, or even nation-building. They use it as a means of challenging common stereotypes that people may have about them and to present more positive representations of themselves to the rest of Europe and the wider world.

Is there a winning formula for a successful Eurovision song?

Not to try to seek a winning formula. Countries that send a “Eurovision-style” entry (usually some form of an Abba or Johnny Logan pastiche) are doomed to failure. To win Eurovision, you need to have a very good song that is imaginatively staged with a confident performer. There usually also needs to be a “moment” in the performance that will grab the audience’s attention, as you do need to ensure that your act is memorable.

Is it true that song entries have become more sensible in recent years?

I think that there’s been a move away from the silly novelty entries, which reached their low point at the 2008 contest, featuring Ireland’s own Dustin the Turkey. The reintroduction of jury voting in 2009 did lead to a move towards better-produced, more credible and stronger entries. That’s not to say that there’s no place for novelty entries – indeed, Israel’s entry this year could fall into that category and it’s currently the strong favourite to win.

In what ways have political tensions between countries influenced point scoring?

Politics probably has a lot less to do with Eurovision and the contest voting patterns than the common stereotypes would suggest. Admittedly, some countries do vote for other countries on a regular basis but this often has less to do with politics and more to do with cultural similarities and sharing music markets; people in these countries like similar types of music and would have heard of the other countries’ Eurovision acts ahead of the contest.

Does everyone really hate the UK? Or does it just tend to score badly because its music is less popular abroad?

No and no. After all, no one hates Switzerland or Slovenia, but these countries have struggled at Eurovision in recent years. Unfortunately, the popularity of UK music does not translate into success at Eurovision, because there is a sense that the UK does not take the contest as seriously as other countries do.

Will Ireland fare better, given Brexit?

No. As last year showed, Brexit has no impact on Eurovision voting patterns. The expectation was that the UK would suffer an adverse effect at last year’s contest, but the UK actually got one of its best results in recent years, solely because it sent a really good performer (Lucie Jones).

What are the best and worst things about your job?

I like working with students, but I especially like throwing something at them that they don’t expect and that forces them to think outside the box, while also helping them to better understand the concepts and ideas that I am trying to teach them…like teaching them through the medium of a rap battle, for instance. What do I not like? Meetings.

Tell us about someone you’ve always admired.

My sisters. They’re both highly intelligent and very good at what they do career-wise, but also spectacularly unselfish, putting other people’s needs before their own and doing many hours of work for other family members, even after a long day at work. They encourage me to be a better person.

What keeps you awake at night?

There’s always the worry, in dealing with students, that you’ll do the wrong thing or say the wrong thing, especially given the amount of pressure that they’re currently dealing with. As a single male in his late forties, who usually really likes his job, the thought of retirement is scary but thankfully retirement age will probably be 80, if and when I get there.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

A nerd. I was the student who always sat at the front in lectures and took copious notes. I did enjoy getting involved in student societies – obviously the geography society, but also drama.

What advice do you give to your students?

My main piece of advice to them is that first-class honours are made in November: when the days are getting colder and darker, when exams and the end of the lecturing years seems very far away and when the many attractions of daytime television can lure unsuspecting students away from the history and philosophy of quantitative geography.

What brings you comfort?

Family. Sleep. Work. Eurovision.

What would improve your working week?

A few hours extra in the working day – there’s just not enough time.

rachael.pells@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

George Boyne has been named the new principal of the University of Aberdeen. Professor Boyne, who is currently pro vice-chancellor of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at Cardiff University, will replace Sir Ian Diamond when he retires in August. Commenting on his new role, Professor Boyne, a double graduate of Aberdeen and an expert on public sector organisations, said that he was looking forward to “leading the university in its ambitions to be inclusive, interdisciplinary and international in reach and quality across the full range of its teaching and research”. Martin Gilbert, chair of the university’s court, said that Professor Boyne would “drive forward our ambitious agenda for growth, excellence and internationalisation”.

Catriona Jackson is to be the new chief executive of Universities Australia. She will succeed Belinda Robinson after two years as the organisation’s deputy chief executive. The former journalist and ministerial adviser has also been chief executive of Science and Technology Australia and director of communications at the Australian National University. Margaret Gardner, vice-chancellor of Monash University and chair of Universities Australia, said that Ms Jackson was an “outstanding communicator who is held in strong regard in higher education, politics and the media” and had “proven herself a skilled and principled advocate”.

Pakistan’s oldest public university has appointed its first female vice-chancellor. Nasira Jabeen has become provisional vice-chancellor of Punjab University, which was founded in 1882, having served as dean of its Institute of Administrative Services.

Andy Long is to become provost and deputy vice-chancellor at the University of Nottingham. He will lead operational planning and academic resources across the university, as well as manage the five faculty pro vice-chancellors. Professor Long is currently pro vice-chancellor of the University of Nottingham’s Faculty of Engineering.

Robert Mun is to become the Australian Research Council’s new executive director for engineering and information sciences. Dr Mun, who joined the ARC from Australia’s Department of Defence on 7 May, is a former chemical engineering researcher who has served as scientific adviser to the Royal Australian Navy.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login