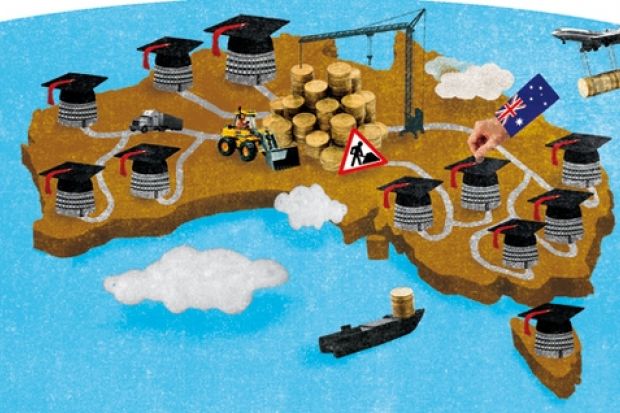

In 2007, a new Labor government came to power in Australia with a platform that gave prominence to a proposed "education revolution". Australia's universities were pleased with the atmosphere of positive consultation and new funding that emerged.

However, the reforms were a long way from simply showering the sector with more money. Proposals were put forward for regulation, quality assurance and reward for performance. A Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency was to be established to oversee both public and private universities and the burgeoning group of non-university providers. Teqsa was given a mandate to adopt a standards-based approach, both academic and non-academic. A research assessment exercise, Excellence in Research for Australia, was to be rolled out from 2011. Targets and performance funding for teaching and learning also were to be introduced through negotiated agreements, known as "compacts", between institutions and government.

Several of these elements will be familiar to colleagues in the UK, and so the Australian experience of the past two years offers some interesting lessons. One is that it is all too easy to underestimate the complexity of reform. Standards and performance measurement are difficult to define and translate into practice, and great care needs to be exercised to ensure that regulation is proportionate to risk and that university autonomy is not unduly compromised.

Over the past two years considerable effort has been invested in the development of the basic architecture of Teqsa, on matters of governance, process and broad outlines of operational standards. We have not yet clarified the even more complex details of how academic standards might be scrutinised. Targets and measures for performance funding have also developed slowly. Although additional funding is always welcomed, universities have accepted some delays in the interests of ensuring that the settings are right.

A corollary of this is that universities need to work closely and consistently with government to ensure that good policy and practice can be secured. For its part, the university sector in Australia has been able to present a united position to the government on the most important issues. As is the case in the UK, Australian higher education over the years has been prone to fracturing into special interest groups, particularly over research matters, and this can easily make the sector appear unduly self-serving and ineffective. On the government side, despite some early unevenness and stressed deadlines, there has been a continuing commitment to consultation and listening to expert advice.

To its credit, the Australian government has held its nerve in the face of continuing post-global financial crisis pressure. Although adjustments have been made, the core elements of the reforms remain intact. Australia's neighbouring region is Asia, where public investment in higher education is rising. Australia, like many other countries, is moving rapidly to a mixed economy of public and private higher education, and the government continues to assert a key role for public funding. Clearly, Australian universities prefer this direction to that of the recent UK reforms.

However, the longer-term outlook is not so clear. The government deferred the issue of continuing core grant funding to another review, led by Jane Lomax-Smith, due to report later this year. There are many issues to resolve in this area, such as consistency in postgraduate coursework funding, the relativities of grant amounts for different disciplines, and the fundamental issue of how much universities need to sustain quality. It is therefore to be hoped that Lomax-Smith can provide some meaty principles to guide the allocation of the public subsidy, and not be sidetracked entirely by complex costing exercises.

For more than a decade, Australian universities have had international student income to offset deficiencies in public funding, but the recent downturn caused by various factors, including a high Australian dollar and stronger competition, has highlighted the delicacy of our situation. International education should not be driven by a need to make up domestic funding shortfalls, and increasing management, audit or private-sector competition will not substitute for the need to ensure adequate basic resources for universities. This is the major remaining challenge for the future, and one made more acute by the ever-expanding scale and scope of the higher education system, which is stretching resources ever further.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?