A fall in the share of higher education aid directed to Africa over the past 20 years is a “great concern” that urgently needs addressing in the light of the continent’s exploding youth population, it has been warned.

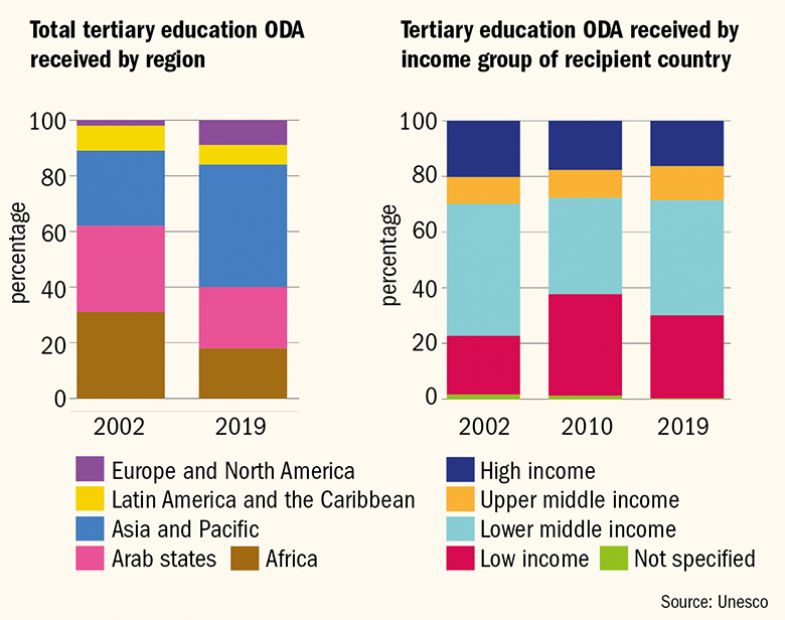

The comments follow a report from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation that revealed the proportion of Official Development Assistance for tertiary education (TE ODA) going to Africa was lower than a fifth (18 per cent) in 2019, down from 31 per cent in 2002.

At the same time, the report suggests that middle-income countries received about 70 per cent of such aid in 2019, far higher than the share going to the lowest-income nations (12 per cent). China on its own received 8 per cent of tertiary aid even though it is also becoming a substantial donor itself.

The analysis used data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and other sources to estimate the amount and types of aid flowing between donor and recipient countries.

It suggests that tertiary overseas aid almost doubled between 2002 and 2019 to about $5.3 billion (£4.3 billion) in 2019, with more than 70 per cent represented by scholarships for students to study in donor country institutions or the support costs associated with this.

Germany ($1.7 billion), which has spent tens of millions supporting Syrian refugees at its institutions, and France ($900 million), with its links to francophone Africa, together accounted for almost half the 2019 total.

The report raises questions about the “substantial” share taken up by student support, given it is money “reinvested in the donor country” and may not always directly benefit recipient nations.

It also says the share of tertiary aid received by upper-middle countries, such as China, “is highly controversial”, while the low share for the poorest nations displayed “a disconnect with the equity principle and the narrative of ODA as a policy to close inequalities”.

There “seems to be further room for improvement in terms of redistributing TE official development assistance from upper-middle countries, mainly towards least developed nations with an imperative need of external resources”, it adds.

Jamil Salmi, former tertiary education coordinator for the World Bank and emeritus professor of higher education policy at Chile’s Diego Portales University, said it was “of great concern to see less ODA going to Africa as a percentage of [the] total”.

“As progress at the primary and secondary education levels [in Africa] continues to grow, the demand for tertiary education will undoubtedly soar. Africa should be a higher priority area, if anything,” he said.

Jude Fransman, co-convener of the Rethinking Research Collaborative and a research fellow at the Open University, said it was questionable whether scholarships that benefited universities in the Global North and led to a brain drain of talent from poorer nations should count as overseas development aid.

“At a transnational level, institutional partnerships involving student exchanges can be more equitable, allowing staff and students from both traditional ‘donor’ and ‘recipient’ countries to learn from each other’s expertise and build sustainable relationships,” she said.

Professor Salmi also said that there were approaches to scholarships that could reduce the risk of brain drain, like programmes that boosted the research conditions in developing nations for returning doctoral graduates or “embedding scholarships in a wider package of support for local tertiary education institutions as part of a clearly defined capacity building plan”.

But he also highlighted the importance of investing in regional initiatives such as the World Bank-supported African Higher Education Centres of Excellence, which has been “pooling resources together across countries” to improve “advanced research and training capacity” on the continent.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login