MEASURING AND MANAGING AN INVISIBLE RESOURCE

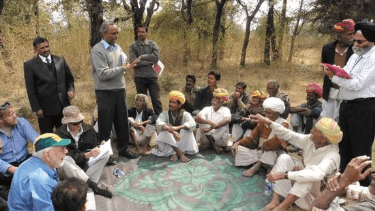

Image: Basant Maheshwari and colleagues meeting with farmers in Sundarpur. (credit N/A)

Putting research in the hands of village communities leads to coordinated and lasting improvements in groundwater management.

In many regions of India, groundwater is the main source of water for local communities, but years of overuse has critically depleted groundwater reserves, with dire implications for water and food security. While there are no easy solutions, Professor Basant Maheshwari’s team at Western’s ‘Australia India Water Centre’ and School of Science has shown that a transdisciplinary approach that brings together different disciplines and empowers local villagers as participants in the research, can open a new pathway for solving this complex problem.

“Groundwater overuse is a serious problem in India and nearby countries, and is becoming significant across South East Asia and Africa,” explains Maheshwari. “Our project is about finding ways to improve the sustainability of groundwater use while improving the livelihood of village communities by solving a complex, people-related problem from a range of perspectives, including technical, social, environmental, economic, agronomic and policy points of view.”

Initiated in 2011 and working in 11 villages across two watersheds in western India, the Managing Aquifer Recharge and Sustaining Groundwater Use through Village-level Intervention (MARVI) project is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, and the Australian Water Partnership. The project is a broad collaboration with the CSIRO, and agricultural research institutions and NGOs in India. The MARVI team put the community and their livelihood at the centre of interventions.

“The way we saw it, we had two options to address this problem. A conventional approach where we collect data, perform some modelling and analysis and develop recommendations, or a transdisciplinary approach where we bring people together to own the problem, engaging water users to monitor groundwater, learn together and develop their own water management science and strategies for collective action,” says Maheshwari.

As Maheshwari recounts, while the conventional approach might have been easier, the project would have ended a long time ago with a low probability of those strategies translating to meaningful action. The alternative approach that the team undertook was time-consuming and difficult, but it has led to real and ongoing actions by communities and is already being replicated in other areas of India.

Through the MARVI project, members of the 11 village communities taking part in the initiative were trained as ‘groundwater informed’ volunteers to help communicate how groundwater supplies fluctuates, and to reliably collect groundwater level and rainfall data.

“Many doubted that villagers with limited formal education would be able to collect reliable groundwater data or understand the groundwater science,” says Maheshwari. “However, the villagers disproved that apprehension and were able to collect reliable data and work closely with researchers.”

Hari Ram, is one of the volunteer farmers from the Dharta watershed who participated in the MARVI project. “In the beginning, we did not know how measuring groundwater depth and rainfall would help us, but we knew that we needed to do something,” he recalls. “Within six months we started getting a feel for how groundwater levels were fluctuating in the wells and how rainfall and groundwater pumping influenced the groundwater levels. This eventually helped us to estimate groundwater availability and decide on how much area we could irrigate until the crop harvest.”

“The participatory, village-level monitoring approach empowers local communities to develop their own groundwater management dialogue and strategies,” says Maheshwari. “By learning that they are pumping from a common pool resource, the communities were able to find their own solutions. Through the newly formed Village Groundwater Cooperatives, farmers were encouraged to work together to tackle their common problems.”

The MARVI project is now being adopted by the Government of India, which is rolling out the programme in seven states covering more than 20,000 villages through a World Bank supported project, the Atal Bhujal Yojana – a National Groundwater Management Initiative.

Need to Know

- Groundwater reserves are becoming critically depleted in India.

- The MARVI project is finding ways to use groundwater more sustainably.

- It empowers local farmers to monitor and manage usage.

For more examples of how Western Sydney University is driving social transformation, refer to their latest, special SDG edition of Future Makers: https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/future-makers/sdgs-issue