On the eve of the economic crisis, economists were congratulating themselves on arriving at the supposedly correct model of the economy and announcing that there would never again be an economic crisis on the scale experienced after the 1929 crash; left to its own devices, the free market was stable and, even if adverse shocks impinged from outside, policies were capable of providing relief. The future was bright. Of course, as is now clear, economists could not have been more wrong.

The last Great Depression was followed by a revolution in economics, but economists are responding to today’s economic crisis in the way astronomers responded to observations that questioned the idea that the Earth was at the centre of the solar system – by tinkering with the extant model rather than overhauling it. For postgraduate-level courses in economics and finance, Munk’s Financial Asset Pricing Theory is a good example of that approach. For undergraduates, Blanchard et al’s Macroeconomics: A European Perspective does a great job of presenting all the usual macro models we taught before the crisis (IS-LM, AD-AS) and also adds useful chapters on financial markets, the euro’s troubles, the causes of the crisis and why the recovery is so slow. Ultimately, however, the authors do not see a revolution as necessary, as they are at pains to point out in their conclusion.

Those who believe, like myself, that a revolution does need to take place will take comfort in the fact that astronomers eventually realised the error of their ways. In economics, such a change will likely come from the younger generations, but only if we can open their eyes to alternative approaches to those found on the present syllabus and in associated macroeconomic textbooks.

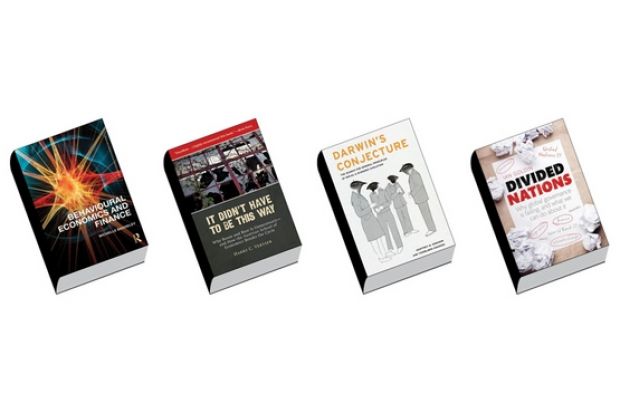

There were always schools of thought on the “periphery” that questioned the assumptions and predictions of the “standard” model. Behavioural economics questions the view that people are rational, fully informed calculating machines. But until recently there were few accessible textbooks to which one could refer students expressing an interest in this area, particularly in the area of macro-applications. With the publication of, for example, Baddeley’s Behavioural Economics and Finance, this has started to change. De Grauwe’s Lectures on Behavioral Macroeconomics shows how behavioural economics can have a drastic effect on our understanding of the macro-economy. Rather than seeing the economy as naturally stable, this approach suggests that instability is inevitable, implying a greater role for policy. Of course, with growing attention comes hardened criticism, including Levine’s quick and easy read Is Behavioral Economics Doomed? The Ordinary versus the Extraordinary.

A second alternative approach is that of the Austrian School, which also views the recent global economic instability as coming from within rather than outside the economic system, but in a way that advocates less and not more government intervention. It Didn’t Have to Be This Way (Veryser) provides a much-needed, readable introduction to this school of thought.

A third alternative approach is Darwinian, applying ideas from the natural sciences to economics. Hodgson and Knudsen’s Darwin’s Conjecture: The Search for General Principles of Social and Economic Evolution offers a rigorous account of how the principles of evolution can help us understand business practices, legal systems and technology.

Unfortunately, few of these approaches receive even a passing mention in the core syllabus. Students are unknowingly blinkered to a whole world of economic research and ideas in desperate need of attention; academics thinking outside the box need to guide them in the right direction.

In addition to looking at alternative theoretical approaches, students should be encouraged to look beyond theory and towards history. Economic history provides a wealth of evidence that is yet to be fully exploited – a sad but inevitable result of its having been crowded out by mathematics. A number of new titles show just how helpful history can be as a testing ground for economic theories and policies: Blyth’s Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea critically considers current austerity policies in a historical context; my own book Markets and Growth in Early Modern Europe uses historical data to provide the first major statistical test of whether markets are sufficient for economic growth, concluding that they are not. Marshall’s The Surprising Design of Market Economies emphasises just how much markets have been a product of the state, a view with which I have sympathy, and Eichengreen’s Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar draws on history to look at the future of international currencies.

Not only does the discipline need to revolutionise but so do institutions of policymaking and global governance. Goldin’s Divided Nations: Why Global Governance Is Failing, and What We Can Do about It argues that we are doing little more than rearranging deckchairs on the Titanic. He points out that “the world has changed in fundamental ways” since the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund developed, and that until they are reformed, we will be unable to meet many of the challenges faced by the global economy.

Of course, reading many of these titles may not lead students to substantially higher marks in examinations, but it will help us to develop a new generation of economists who can think independently, question standard models and ultimately build a stronger and more successful economy.

Tap and scroll down for links to all Economics textbooks

Or view PDF below

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?