A colleague recently referred to archaeologists who had been involved in a major argument as "dinosaurs". I was reminded of this rather swingeing assessment as I read this short, passionately argued book. Then, as now, the controversy did not relate to archaeological methods or the interpretation of an important site: both focus on what has been described as the "social face" of archaeology. In the 1980s, the issue was whether archaeologists should abide by a UN boycott of South Africa and not allow South African colleagues to attend a conference (written up by Peter Ucko in the 1987 book Academic Freedom and Apartheid: the World Archaeological Congress). Now the division is not over a conference but the issue of ownership of, and control over, the artefacts of the past - an issue hotly debated at that conference in 1986.

James Cuno, head of the Art Institute of Chicago and former director of the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Harvard University Art Museums, argues that claims for the restitution of cultural heritage are politically motivated by nationalistic agendas. This is not news; to dismiss the debate over restitution merely on the grounds that the debate is political and nationalistic does little for the defence of so-called encyclopaedic museums.

Cuno's thesis is that the encyclopaedic museums are above politics, above nationalism, and are instead bastions of liberal thought and learning: "a repository of things, and knowledge, dedicated to the dissemination of learning and to the museum's role as a force for understanding, tolerance, and the dissipation of ignorance and superstition".

This is fine until you analyse it. On whose terms is the learning defined? Presumably it is to be provided within the context of the Enlightenment that breeds the Western scientific tradition - but what about all other traditions? How does the aspiration of tolerance sit with the refusal to even contemplate the return of cultural heritage to those who claim a prior, or greater, ownership?

Cuno builds his argument around the undoubted nationalistic agendas of some countries. But what about claims for restitution that may well be equally political but in different ways - for example those originating from indigenous communities? Such issues are dismissed by Cuno when he states that there have never been claims by museums on the artefacts of "primitive cultures" found within the borders of the present US. This is, of course, just plain wrong and it took until the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act for Native Americans to regain the upper hand over the ownership, management and control of the sacred objects and human remains of their tribal groups.

In ignoring the wider debates, Cuno not only restricts himself but also ignores the value that can be gained by engaging with others. Collaboration with indigenous groups has led increasingly to better relations between museums and indigenous communities. Where better relations have developed, knowledge of artefacts has frequently increased; and these relations are founded on mutual trust, tolerance and an acceptance that world-views may on occasion be diametrically opposed.

Cuno confronts frictions between his museums and archaeologists. He writes in a clear, straightforward and unambiguous way that engages the reader with his concerns for the artefacts in encyclopaedic museums. "The Rosetta Stone was found without archaeological context. In the terms of the current argument between museums and archaeologists over the relative value of unexcavated antiquities, the Rosetta Stone would be pronounced meaningless," he says.

"Yes," we cry: to the barricades to protect this and all other artefacts from being rendered "meaningless" by archaeologists. Until we look again at the claim, that is, and see that it is utterly false. No archaeologist would argue that the Rosetta Stone was meaningless. What many, if not most, archaeologists would lament is the loss of additional information that may well have been provided had the stone been excavated carefully from its archaeological context. To put false arguments into your opponents' mouths is to undermine your own.

Despite such omissions and confusions there is much to agree with in this book. Few would argue that "antiquities should be distributed around the world to better ensure their preservation, broaden our knowledge of them, and increase the world's access to them". But many would question how such distribution is to be achieved. The author's position is clear when he admits that he failed to take into account the lack of provenance of artefacts he purchased in 1998 - that is, some 28 years after the 1970 Unesco Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. That a museum director could have been oblivious to the issue in 1998 is staggering, almost unbelievable.

And then the penny drops: what Cuno is talking about is encyclopaedic art museums. The importance and value of artefacts is measured not in their ability to impart knowledge of past or present communities but rather is measured in artistic terms: "This piece is so beautiful that it should be in an encyclopaedic art museum." And the museum will pay to have it. He is of course correct in arguing that the Nok sculptures were not made for Nigeria - Nigeria did not exist when the sculptures were crafted - but equally certainly they were not made to be in a museum in New York or London or Berlin.

Cuno discusses the origins of the British Museum as the exemplar of the encyclopaedic art museum, as an "Enlightenment ambition", and he stresses that "this is not a nationalist argument". I agree that it is not - it is an imperialist argument. In the face of such a world-view, is it any wonder that many countries that have lost considerable amounts of material from sites within their present-day national borders attempt to confront such colonialism? That they attempt to do this through legal means is not surprising when those in the position of power - such as directors of encyclopaedic art museums - refuse even to contemplate dialogue.

The nationalistic agenda is certainly not the best or most defensible. But if so-called source countries do not have an agenda that attempts in a crude way to level the playing field, then the present free-for-all continues, where the strong (in other words, the rich) dominate and the bully rules the playground...

Yes, let's have museums around the world with examples of material from around the world, but let's achieve it through dialogue and agreement and not through the continuation of a system that is so obviously flawed. Dialogue between indigenous groups and museums has led to a greater understanding and awareness of each other's world-views and has led to some fantastic permanent exhibitions. I can only salivate at the thought of the exhibitions that could be put on, permanently, in encyclopaedic museums if all protagonists were to work together. The first to do this need to be those in control at present: the directors of the encyclopaedic art museums. They have to have the courage to open the discussion; some have started this process, albeit, I would suggest, reluctantly. They are badly served by this book that entrenches their position.

I assume that many will hope and some I know will pray that this book represents the last death throes of a failed traditional world-view: the dominance of the many by the (very) few; the dominance of a Western scientific tradition over all others; the dominance of a closed view clinging, perhaps subconsciously, to what can only be described as colonial oppression. Perhaps if a dinosaur could have written a book arguing against its extinction, it would have read like this.

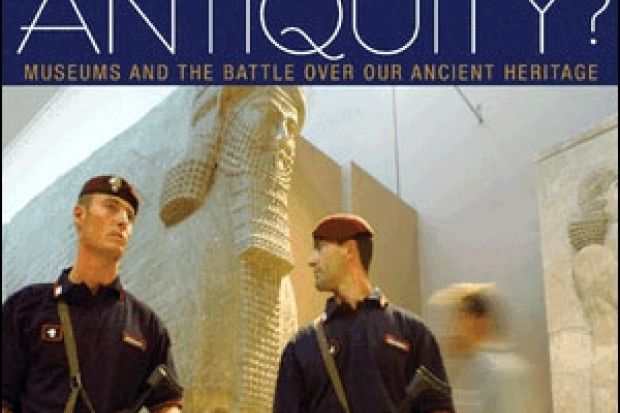

Who Owns Antiquity? Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage

By James Cuno

Princeton University Press 256pp, £14.95

ISBN 9780691137124

Published 1 June 2008

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login