The unemphatic title of Cora Gilroy-Ware’s book accurately describes its subject matter but belies its intellectual energy and originality. The author begins with a bold binary opposition, derived from John Keats’ poem The Fall of Hyperion: this sets the “dreamer”, who wishes to change the world, in opposition to the “poet”, who seeks “no wonder but the human face, no music but a happy noted voice”. “Dreaming” and “Poetry”, Gilroy-Ware argues, can also be distinguished in approaches to classical sculpture during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

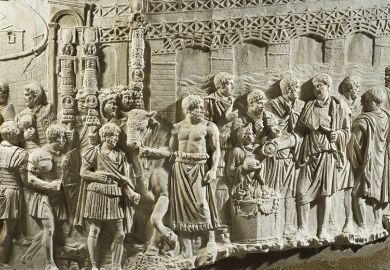

Many neoclassical artists seized upon Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s description of the beauty of ancient Greek art as “nurtured by a lack of constraints” – an effect of both culture and climate. For radical sculptors such as Thomas Banks (who ranks among the “dreamers”), one implication of this idea was that art might be improved by greater political freedom and egalitarianism. “Poetic” artists, on the other hand, represented most strikingly by Antonio Canova, unmoored the body from political discourse by emphasising the sensuality of its surface: amusingly, Gilroy-Ware suggests that it is unsurprising that Napoleon rejected Canova’s sculpture of him, since the figure of the emperor is “relaxed almost to the point of languor”.

While Canova supplies a recurrent point of reference, the book considers a number of lesser-known, British artists: not only John Flaxman (a “poet”, who “smoothened, feminized and sensualized…the antique”) and John Gibson (another “poet”, enhancing the surface of his sculptures and embellishing them with colour), but also Banks, the anti-radical “dreaming” sculptor John Bacon and the painters William Etty and Henry Howard (the latter both “poet” and “dreamer”).

Gilroy-Ware approaches her material with a meticulous attention to detail and a sharp awareness of incipient complexities and contradictions: after viewing the Elgin Marbles in 1808, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon acclaims the ruggedly muscular male classical body (as opposed to the smoother version favoured by “poets”) and uses this as the basis for a “dreaming”, politicised racial hierarchy, but does so despite his fascination with the physical perfection of his black model Wilson, a sailor from Boston.

One of the impressive aspects of this book is that it focuses on concepts that are formed within both literary texts and art – such as sensuality and sweetness – and resolutely pins them down. Sensuality is paradoxical, since it is “normally associated with earthly and animalistic drives”, yet “Poetic art…places [it] in a remote realm untroubled by mortal concerns”. The term “sweet”, much used by Keats, denotes atemporality, delicacy, a “flowing line” and an elimination of “all elements that are unpalatable”.

Later chapters map out narratives in which the classical ideal transmutes (among other options) into a ripplingly muscular yet “sexless” version of masculinity, as in Richard Westmacott’s Achilles in the Wellington Monument at London’s Hyde Park Corner, or into sculptures of prepubescent girls by artists such as Richard James Wyatt: figures uneasily insulated against “libidinal interpretations” by their mawkish innocence.

The author is unusual among art historians in taking concepts from a literary source and using them to direct her analysis of visual culture. In doing so, she destabilises conventional categories and suggests lively new ways of thinking about works of art that have often been taken for granted or simply ignored.

Chloe Chard is a literary historian who is writing a book about travel, laughter and visual culture.

The Classical Body in Romantic Britain

By Cora Gilroy-Ware

Yale University Press, 320pp, £40.00

ISBN 9781913107062

Published 14 April 2020

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Radical take or art for art’s sake

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?