Saloua Raouda Choucair

Tate Modern, London

Until 20 October

This summer, a quiet rear wing of Tate Modern’s fourth floor will be home to an exhibition showcasing the work of the Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair. In customarily confident Tate style, a garish orange banner bearing the artist’s name emblazons the Bankside facade, declaring her arrival with an indefatigable self-assurance. And yet if Choucair’s name were to you puzzlingly unfamiliar, this would be because this brave new collection presents her first major museum exhibition and, at the age of 97, the late debut of an international artist of considerable gravity.

Even in her native Beirut, where a vivacious, pushy and young art “set” stridently leads the buoyant Middle Eastern modern art scene, Choucair’s name remains an esteemed but archived memory. Tate’s collection (following on the heels of a 2011 retrospective at the Beirut Exhibition Center) presents the culmination of more than 60 years of patient and prolific work. Despite a few pieces in the permanent collection (purchases intelligently advised by curator Jessica Morgan), Choucair’s work is largely unsold and unseen, making this gathering of her work either bravely speculative or excitingly foolish.

Comprising more than 120 pieces, the exhibition is invigoratingly assorted in the influences and idiosyncrasies it presents. The show narrates the distinct phases of Choucair’s development, beginning with likeable early oils and branching into extraordinarily abstract sculptures rendered with a bewildering agility in a range of materials. Taken altogether, this exhibition is a small triumph, attesting once more to Tate’s trademark nerve in championing the most unassuming artists and, following on from recent retrospectives of Louise Bourgeois and Yayoi Kusama, extending its exemplary attention to the work of older women. Perhaps most movingly, in the case of Choucair, it miraculously rescues for posterity what might be the last bloom of a modest artist’s lifelong quiet flowering.

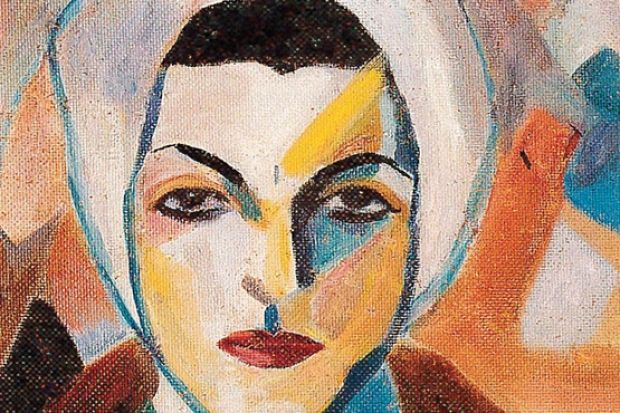

Saloua Raouda Choucair was born in Beirut in 1916 and began painting under the guidance of Lebanese landscape artists Mustafa Farroukh and Omar Onsi. As the exhibition indicates, a period of training in Paris under the tutelage of Fernand Léger in the late 1940s proved to be formative; Léger’s populist Cubism and the modish Parisian forms of Modernism are overpoweringly in evidence in the experimental phases of Choucair’s jejune work. The exhibition’s opening room details predictable dabblings in the optical art of the mid-20th century, developing into Mondrianesque lines, severe and segmental, with cavorting Matisse-inspired nudes, shapely and bright. These paintings offer diligent dilutions of Modernist adventures in abstraction, readily recognisable riffs on colour and perspective, and a reproduction of those concerns of the French masters they so capably mimic. But that magpieish impulse to borrow and restate also betrays Choucair’s hunger, and the work presents her thoughtful and steady trial- and-error-ing, a quizzical puzzling-out of how to be a young Arab woman in 1940s Paris and to follow “after” the Légers and Le Corbusiers encircling her.

The engagement with Le Corbusier is fascinatingly documented in a small collection of Choucair’s personal photographs of the architect’s first Modernist residential housing site in Marseille. The grainy images of Choucair smiling from the sparse interiors of the apartments of the Unité d’Habitation (1947-52) are accompanied by a set of handwritten notes. Here, Choucair’s exquisite Arabic scrawl stands in stark juxtaposition to Le Corbusier’s elegant European spaces, dramatically recalibrating her French Modernist identifications. To characterise Choucair’s work as a kind of European Modernism transferred eastward would be to misread as “interpretation” what are instead radical acts of extension. The gift of Choucair’s work is its melding of Modernism with the peculiar terms of her own Arab idiom too, in ways that extend and so challenge the conventionally acknowledged parameters of both traditions.

The quiet anchoring of Choucair’s work in its Islamic Arab context plays no small part in this idea of a Modernist extension. This is most apparent in the installation titled Poem Wall (1963-65), which at first glance presents as an anodyne white wooden construction of interlocked blocks, fitted together like a clumsy jigsaw, but which on further inspection opens into a three-dimensional text-art puzzle, playing on the modern angularity of Kufic Arabic script. In Choucair’s thoughtful hands, ultra- chic abstract Modernism reveals itself as a classical 7th-century Koranic typeface. How far this fluent traversal of influences is agility or promiscuity, veering between unintended indecision and a planned playfulness, is unclear. Clearer, though, is the way in which Choucair’s marriage of Modernist art to medieval Islam seems to perceive a sympathy in the advocacy of abstraction by one and the prohibitions of figuration by the other. In the figure of Choucair herself, these influences, a secular Islam and an experimental Modernism, intersect almost uniquely. Indeed, much of the later work, the series of stacked and curved interlocking sculptural parts of wholes, are articulated in Choucair’s own distinct idiom of “modules” and “duals”.

Choucair’s decisive shift from two-dimensional to three-dimensional forms serves to further fuse her Arab-Modernist abstractions with mathematical preoccupations. This is a natural fellowship in so far as the patient repetitions of oddly shaped blocks and spheres present in different materials a kind of abstracted Islamic geometry. Here the collection carries forward the perspectival patterns and motifs of the earlier oils into a staggering array of sculptural registers: the same or similar abstract interlocking units, some spherical, others rectangular, each algorithmically iterated and rendered variously in ceramics, stone, fibreglass, varnished woods, glazed stoneware, enamelled terracotta and buffed brass and silver. These curiously tactile configurations of interlocked pieces present both their totality and their segmentation simultaneously; the stacked “modules”, ever ready to tumble, sustain their solidity in peculiar co-relation to their very precariousness, while the smooth curvatures of fitted “duals” suggest the yielding suppleness of bodies despite their precisely measured inanimate forms.

These “rhythmical compositions”, as Choucair identifies them, are worked through as peaceable rather than panicked repetitions. There is, in her repetition, something like a mute reconciliation to that paradox that our repetitions are compelled by the possibility that there is something more yet to be said or done and known, even as one might be bound by the impossibility of ever saying, doing or knowing it enough. Indeed, Choucair’s repeated modulations, stacks and structures rendered in wood and clay, and bronze and fibreglass, are by turns both atavistic and futuristic. At times, the totemic varnished wood structures point up a primitivist Phoenician origin as vividly as the stacked steel cages promise a Modernist future.

If the politics of this Arab experiment in abstraction are difficult to identify, the exhibition, rather clumsily, points to a battered oil on canvas design, titled Two=One (1947). This work bears the traces of bomb damage dating back to 1984 from the Lebanese civil war. And yet in many ways, this is the least interesting of items in an otherwise curious collection. More telling than the image itself is Choucair’s apparent disregard for it. In this exhibition space, the painting seems to tell the story she doesn’t care to, but the more important story, expressed with particular strength and certainty in those later sculptural works, is that of an artist’s obstinate insistence on the place of complex abstraction even amid the crudity of decades of political violence. In Trajectory of the Arc (1972-74), a beautifully thin mesh of nylon threads is elongated across a Plexiglass sheet, twisting into an arc and forming an elegantly realised mathematical line drawing: the piece is exquisitely lovely and yet obdurately unyielding, both delicate and strong. At 97, this is Choucair’s legacy - one that this exhibition movingly begins to document just as she herself leaves it behind.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?