Successful taxation depends upon fairness, argue political scientists Kenneth Scheve and David Stasavage, and this they equate to perceptions of equal treatment. However, they also suggest that we do not agree on what equal treatment means.

Their book explores three perceptions of fairness. The first is literally equal treatment, which they interpret as a poll tax – and then largely ignore: poll taxes have a poor history in the modern world.

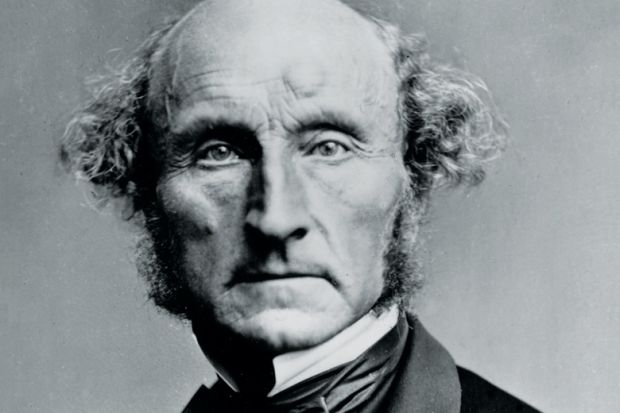

More surprising is their dismissal of the idea that when it comes to taxation, fairness is related to ability to pay. This idea, which they largely attribute to John Stuart Mill (pictured), was, they claim, economically discredited by the end of the 19th century and has had a chequered history since then. This leaves only their third version of fairness, which they call compensatory payment, to justify higher rates of tax on the rich.

Scheve and Stasavage suggest that compensatory payment as the basis for taxation is accepted as fair when a government creates a situation where a palpable benefit arises to one group in society that another cannot enjoy. Disparate tax rates then correct for the resulting perceived injustice. According to the authors, their research suggests that this is the only justification for taxing the rich more than anyone else.

The problem for those who still believe in progressive taxation is that Scheve and Stasavage then argue that it is only the mass mobilisation of labour in wartime (which has happened only twice in history) that creates the politically acceptable environment for these compensatory payments. This, they say, is because mass mobilisation is an imposition akin to taxation that cannot be levied on capital because capital cannot forgo its life in the pursuit of national gain and as a result capital must compensate labour when mass mobilisation takes place.

The authors have done their homework: they present a large amount of data to support their claim, but I am not convinced. First, the choice of data – which are almost wholly national and largely concerning income tax and inheritance tax – is too limited. The impact of the offshore world, trusts, corporate taxes, lower rates of capital gains tax, and tax avoidance and evasion are given scant attention, while the fact that economies are in effect closed in wartime and increasingly open thereafter is never mentioned.

Second, other issues, such as changes in income distribution, the rise of the middle classes, the mass engagement of women in the workforce in the modern era and the impact of political and economic hegemony are also ignored.

Third, that tax rates in war are not compensatory, but are necessitated by the sheer scale of government spending and the need to limit inflation in whatever way is possible, is too readily dismissed. That war is an outlier that we should ignore is an idea the book just does not entertain.

The result is a work that feels dogmatic, however good the scholarship. It appears that its whole purpose is to suggest that no situation where taxing the rich more than the rest of the population can be justified now exists, or is ever likely to recur. But at no point is the fact that we actually now have regressive taxation for the richest justified, and the basis for modern compensatory payments is too lightly dismissed. Financial market failure, unjustified pre-distribution of income and wealth, the prevalence of rents in the modern economy and environmental justification for reducing consumption by a few are hardly mentioned.

The result is that there may be an argument implicit in this book, but not the one it presents.

Richard Murphy is professor of practice in international political economy, City University London, and author of The Joy of Tax (2015).

Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe

By Kenneth Scheve and David Stasavage

Princeton University Press, 288pp, £22.95

ISBN 9780691165455 and 9781400880379 (e-book)

Published 15 April 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login