Writing a history of religion is much like writing a history of water. Water is everywhere: we notice only unexpected superabundance or troubling deficits. While we might imagine that a history of water is a story of lakes, rivers and seas, we would quickly discover that water is a ubiquitous entity; its pervasiveness means that it saturates, almost unseen, our very selves. So it is with religion. Even in a modern world organised by fantasies of divisions between church and state, religion is everywhere: inseparable from other activities at the level of the human person and seeping into the only notionally distinct arenas of economics, politics, social networks and cuisine.

In attempting to write his new history, Jörg Rüpke, the distinguished historian of Roman religions, has taken on an audacious task. The result, a translated and slightly updated version of his similarly titled 2016 German work, strikes a remarkable balance between imparting the rich data of a lifetime studying the scholarly “rivers” of ancient religion – temples, burial rituals, priests, mystery religions, domestic deities, initiation rites and so forth – and probing the theoretical and methodological constraints of the category of “religion” itself. There are few scholars of any period who command the theoretical and the phenomenological with the same degree of proficiency.

In its enormous scope, the book charts the “story” and “narrative” of “lived religion” from the Iron Age to late antiquity. A study this broad requires a facility in the material culture of the ancient world: the dearth of literary texts from the early period necessarily entails getting one’s hands dirty in the archaeology of the Mediterranean, and at this Rüpke is singularly talented. In the same way, later in the book, he refreshingly engages with the questions of real and imagined communities and the invention of textualised communities.

Given the seismic shift that takes place with the ascent of Christianity, Rüpke is self-consciously and appropriately interested in change: specifically, the changing functions and conceptions of religion. Drawing on the work of Russell McCutcheon and Brent Nongbri, he notes the importance of the rise of the category of “religion” during the early Christian period. It was only then, after centuries of functioning as sets of interwoven practices, that religions came to be seen as communal networks conscious of their own boundaries.

In a book of this breadth, there are places where authorial expertise wears thin. Although Rüpke only occasionally discusses the religious worlds of the monotheists, the many matter-of-fact statements about Jewish and early Christian texts and traditions rely heavily on continental European scholarship and, in some instances, on fairly idiosyncratic theories. Similarly, despite its ambitions, it is a book focused more on Greece and Italy than the wider limits of the Roman Empire.

With some 200 pages of footnotes and bibliography (to say nothing of the thicket-dense prose), this is undoubtedly a book for fellow scholars. But it is a tour de force – a volume that will quench the thirst of the classicists and historians who reach for it.

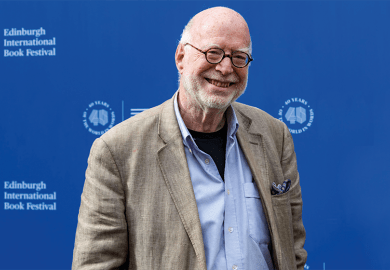

Candida Moss is Cadbury professor of theology at the University of Birmingham.

Pantheon: A New History of Roman Religion

By Jörg Rüpke; translated by David M. B. Richardson

Princeton University Press, 576pp, £32.95

ISBN 9780691156835

Published 21 February 2018

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How we came to worship the gods

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login