Have you ever read a book that felt as if it had been written especially for you, one that speaks to both your professional interests and your personal narrative pleasures, that simultaneously stimulates your understanding and surprises your sense of whimsy? Curious Subjects: Women and the Trials of Realism is that book for me. Hilary Schor focuses squarely on the most canonical of Victorian novels - Vanity Fair, Bleak House, Hard Times, Middlemarch - but just when you were sure that there could not possibly be anything new to say about such mainstays of 19th- century fiction, she dazzles her reader with fresh perspectives couched in a vibrant prose style. Her contemporary and postmodern references range effortlessly from the literary world of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale to Joss Whedon’s virtuoso fantasy experiments in Firefly and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Still, her discussion throughout remains anchored firmly in its cultural context, enriched with the gleanings of a long career devoted to the Victorian age. Indeed, her account of Thackeray taking his daughters to a party “with the skirts of their stiff muslin frocks actually thrown over their heads, so that they should not crumple them in the carriage!” is worth the cost of the entire book for the advice he offers his girls: “If you are not able to enter the world with your dress in its proper place, I say stay at home.” Erudite, witty and lucid, Schor’s study charms and informs in equal measure.

The curious heroine develops as a creature of agency, who asserts her right to know, who tests the boundaries set by the law of the father/husband

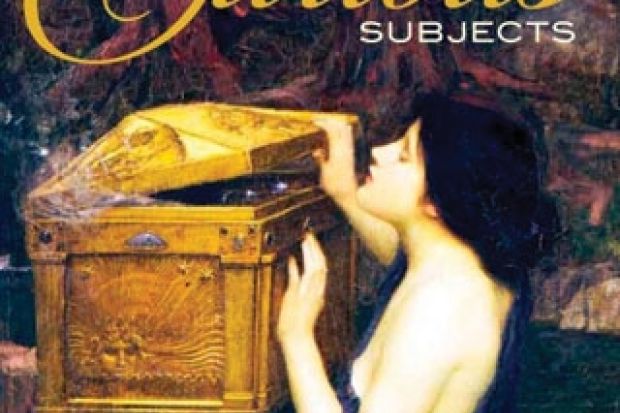

More than 20 years ago, in Scheherezade in the Marketplace, Schor explored the career of the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell through the lens of the consummate female storyteller of the Thousand and One Nights who plays on her husband’s desire to satisfy his narrative curiosity and thereby preserves her life. In Curious Subjects, Schor shifts her attention from masculine to feminine curiosity and its central role in the development of both realist fiction and female subjectivity: “My argument”, she writes, “is not only that without curiosity there would never be any such thing as the realist novel, but that it was the novel that brought the modern feminist subject into being.” Taking Pandora and Bluebeard’s wife - those archetypes of transgressive female curiosity - as touchstones, Schor traces the recurrent question of the knowledge women seek and its function in the history of the novel. The hidden knowledge of the “bloody chamber” is usually read as sexual experience, and the heroines of courtship novels are all in some degree unworldly wives of Bluebeard in search of the knowledge that marriage will bring. Schor argues, however, that much more is at stake: “In the realist novel, women do not ‘choose’ in order to get married; they enter the marriage plot because it was the one place where they had anything that looked like choice. They didn’t choose to marry; they married in order to choose, and they do so in a world of myth, fairy tale, contract and law.”

The curious heroine develops as a creature of agency, one who asserts her right to know, who tests the boundaries set by the law of the father/husband, who ultimately chooses knowledge over innocence, whether she is a Louisa Gradgrind exploring the limitations and possibilities of marriage in her quest for subjectivity, or a Becky Sharp who challenges orthodox femininity to shape and reshape her own destiny. Such heroines, Schor argues, continue to shape our literary world: “The Bluebeard plot shows up everywhere from contemporary fiction and graphic novels to science fiction and modernist poetry. The curious heroine, in short, outlived the legal framework that gave her form.”

We might regard Schor herself as a curious scholarly heroine, one prone to wonder what might happen if we read familiar stories from a different perspective or juxtapose unlikely texts to see if they then tell a different tale.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?