Conventional accounts of Modernism, especially in architecture and town planning, create the erroneous impression that minimalist, history-rejecting, theory-driven and self-referential tendencies were what it was all about between the wars. There was another side, however, to what architectural critic Osbert Lancaster pithily termed “Bauhaus balls”, set in aspic as “The International Style” by the Museum of Modern Art, New York and enshrined in Nikolaus Pevsner’s outrageously biased “grand narratives”. That side was eclectic (embracing not only popular culture, but also the absurd and surreal), and drew on half-invented history, creating an unhistoricist evocation of the past: this was high camp, light-hearted and amusing.

So-called “functionalism” was very much a minority obsession, for the vast majority of British people refused to succumb to its limited charms. They did not want a “machine for living” so much as a place where they could be comfortable and create their own familiar, pleasant spaces. There was an obvious reason why International Modernism was often kept at arm’s length, and that was because the severe austerities of minimalist interiors were more about the coercive programmes of their designers than responses to clients’ wishes. As Dorothy Todd and Raymond Mortimer put it in The New Interior Decoration (1929), “we need fantasy, imagination, wit in our houses…The Corbusier style of decoration is as formal as the old French salon… we require our houses to be quieter, more informal, more personal.”

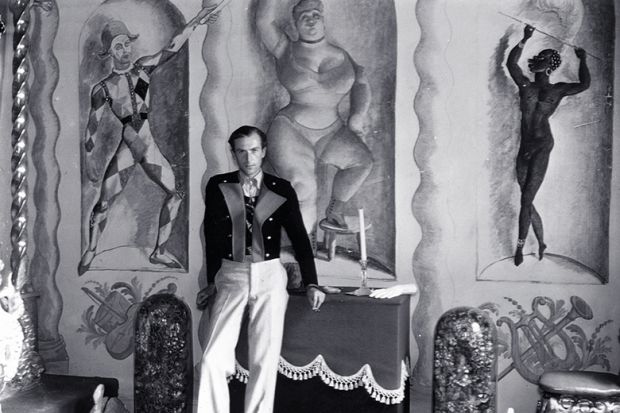

Jane Stevenson pursues interconnected pluralist, undoctrinaire themes that affected all the arts of the period: she argues that “refuseniks” did not merely reject the directions taken by the so-called avant-garde, but created a counter-movement that, in its “cogent set of responses to the problems” of Modernity, can be called “modern baroque”. In architecture, it was also named “decorators’ baroque” and, since many interior designers and decorators were homosexual, irreverently labelled “buggers’ baroque”. That all-embracing tag would include Lord Berners’ multicoloured doves and his 1937 novel The Girls of Radcliff Hall (in which an all-male milieu is encapsulated in a girls’ school story); “hetties” and “nancies” in the “MacSpaunday” circle around the poets Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender, W. H. Auden and Cecil Day-Lewis; Noël Coward, Cecil Beaton et al; and the high-camp world of Ronald Firbank. The last was conjured in the ultra-baroque roseate glow of his novel Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli (1926), where, in the Cathedral of Clemenza, clad only in his gorgeous mitre, the Primate, in pursuit of a choirboy, “swooped” to his death, and paternostering Phoebe Poco piously used her rosary beads to preserve His Eminence’s detumescent modesty.

Stevenson’s is a beautifully written account of modern baroque in its many guises: that counter-culture had a lively eclecticism that was absent in mainstream Modernism, from which choice had been eliminated. She describes the social nuances of the period, the perception that the arts were in the hands of a “pack of pansies” (which, to a remarkable extent, was true), the influence of well-connected lesbians and indeed a panorama of queerness that stood in sharp contrast to the male-dominated (and drearily humourless) austerity of mainstream Modernism. There were, however, designs such as Mae West sofas, Dalí lobster telephones and upholstered walls that perhaps verged more on kitsch than baroque.

The book contains some errors: the architect and painter Ernest George, although important, was not “Earnest”, and John Gloag was not an architect. More illustrations and some colour would have helped. However, it is scholarly, diverting and fascinating, all at once: a bracing draught that genuinely fills a huge void, an essential read to understand a period in all its diversity.

James Stevens Curl’s Making Dystopia will be published by Oxford University Press in August.

Baroque between the Wars: Alternative Style in the Arts, 1918-1939

By Jane Stevenson

Oxford University Press

336pp, £35.00

ISBN 9780198808770

Published 11 January 2018

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?