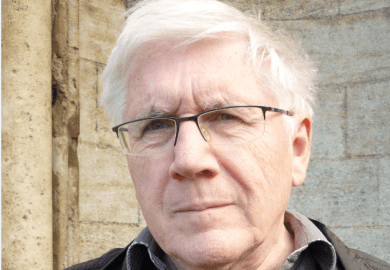

UNSW Sydney material scientist Sean Li heads a collaborative project with China’s Hangzhou Cable Company to develop more efficient power lines. The goal is to boost electricity transmission in China by 5 per cent, producing an annual saving of 275 terawatt hours – more than Australia’s total electricity consumption. Meanwhile, Professor Li and his team have developed a see-through, flexible material that can be used to produce transistors so small that they are in effect two-dimensional. The advance, published in Nature earlier this year, paves the way for a new generation of transparent wearable electronics.

Where and when were you born?

Canton, now Guangzhou, in 1962.

How has that shaped you?

I grew up on a campus. My father was a material science engineering academic at South China University of Technology. My mum was a medical doctor. I picked material science engineering because my father did it. He was working on polymers, but he asked me to go into physical metallurgy, which is what all material science engineering developed from.

You taught in China and Singapore before coming to Australia. What was the biggest difference?

In Singapore, everything was set up and ready for new academics. Your office, the new desk, the computers – wow! Coming here to Australia was quite a surprise. I had only A$20,000 [£11,400] of start-up funding to establish my lab. My room had been freshly painted, but it was empty. The school manager said: “Hey Sean, go get whatever you like.” I was so happy. I went to the department store and bought a very nice desk and the computer with the best configurations. Then I received the bill from the school. “What’s this?” I asked. “Well, you need to pay for it, right?” “How?” I asked. “From your A$20,000 start-up.” I was shocked. Now, my team has the most advanced lab of its kind in Australia – a world-class facility with more than A$16 million of equipment.

Which approach is better?

At that time, the Australian approach was a kind of hunger therapy. It turned you into a tiger, actively hunting for funding. When you have ability and energy but you don’t have money, what are you going to do? Here and there, little by little, you build it up. In Australia, as long as you work hard and demonstrate your capability, you get the reward. The institution is happy to support you. That doesn’t necessarily happen in other cultures. Some people do very well and get a lot of support; others may not. It depends, sometimes, not only on your capability but also on political factors or human relationships. Here in Australia, those relationships are not so critical.

What is your secret for finding industry collaborators?

After I got my bachelor’s degree, I worked as a shipyard engineer for two years. I also worked for a very short time as a foreign exchange broker in Guangzhou. Working in industry teaches you to speak industry’s language. In the US, many universities take academics from industry – IBM, Motorola, companies like that. Here in Australia, most academics come directly from their PhD, and lack understanding of industry’s needs. That’s important, because for every dollar industry invests with you, they want to see two or three dollars returned.

How can universities make their research more attractive to industry?

First, we need to consider improving the promotion criteria in academia. Australian universities compete with the US, Canada, UK, Europe and Singapore for international students. This can make them very rankings-conscious, focused on citations, publications and h-indices. Academics’ track records, which are usually based on these sorts of indicators, tend to determine success in funding applications. This can disadvantage those who have creative ideas but lack competitive track records.

How can researchers get ahead of the game?

We need an environment that allows academics to pursue their passions in a single-minded way, perhaps for their whole lives. [UNSW photovoltaic pioneer] Martin Green is a good example. He just kept following his interest, his passion. You accumulate experience and eventually you become a leader. If you follow what the others are doing, you won’t have that accumulated experience.

There is intense global competition in the development of transistors and computer chips. Why choose to work in such a hotly contested area?

In terms of manufacturing, Australia needs to focus on high-end technologies in which China is not already leading. China has the world’s largest market, super manufacturing capability, a giant supply chain network and lower labour costs, which are difficult to compete with. Our team has accumulated knowledge in nanoscale transistors. We are leading the game in this area by two years. And we are not sitting around waiting for the others to catch up.

What do you like most about academia?

The most important thing is freedom. Freedom in how you use your time; freedom to pursue things that interest you. If you don’t have freedom, why would you want to become an academic?

What do you dislike most about academia?

It’s not exactly a dislike. But the nature of academia is that we’re running a marathon, and it’s not about who wins – it’s more about who’s the last to give up. You just have to keep running. When funding opportunities come, you have to submit applications. Whether you win funding is often a matter of luck, but whether you put in an application is a matter of attitude. They’re different things, and attitude is more important. You might say: “I’ve already submitted so many unsuccessful applications – forget it!” It’s boring and stressful, but you have to keep trying. You keep running. Never give up. Never say fail.

If you were universities minister for a day, what would you do?

The important thing is focused investment. We need research equipment at scale to have a real impact. Sometimes there’s an attitude that if you got some funding this year, you won’t get it next year. If that’s the way we keep doing things, we’ll get nowhere.

john.ross@timeshighereducation.com

CV

1983 Bachelor of engineering, Wuhan University of Technology

1983 Engineer, Wenchong Shipyard, Guangzhou

1988 Master of engineering, South China University of Technology

1988 Lecturer, Analytical Centre, Guangdong University of Technology

1998 PhD, University of Auckland

1998 School of Materials Engineering, Nanyang Technological University

2005-present School of Materials Science and Engineering, UNSW Sydney

2018-present Director, UNSW Materials and Manufacturing Futures Institute

Appointments

Deborah Longworth has been confirmed as pro vice-chancellor for education at the University of Birmingham. She has held the post on an interim basis since the end of last year and before that was deputy pro vice-chancellor (student academic experience) and head of the department of English literature. Professor Longworth, who has been at Birmingham since 1998, said she would work with staff and students to create “a truly inspirational and transformative education, and an academic community in which all are included and supported to thrive”.

Leigh Chalmers has been promoted to vice-principal and university secretary at the University of Edinburgh. She is currently deputy secretary, governance and legal. The appointment completes a series of changes to Edinburgh’s senior leadership team, with new appointments including Kim Graham as provost, Christina Boswell as vice-principal for research and enterprise, Iain Gordon as vice-principal and head of the College of Science and Engineering, and Sarah Prescott as vice-principal and head of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. Principal Peter Mathieson said the appointments would help Edinburgh to “build on [its] success”.

Arig al Shaibah is the new vice-president for equity and inclusion at the University of British Columbia. She previously held the same post at McMaster University.

Chris Harty is joining London South Bank University as dean of the School of the Built Environment and Architecture. He was previously head of the School of the Built Environment at the University of Reading.

Florencia Rodriguez has been named director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is currently lecturer in architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Abla Mehio Sibai has been appointed dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the American University of Beirut, having held the post on an interim basis since September 2020.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?