Dark and urgent warnings about the imminent death of the academic humanities are sweeping the Anglo-American world. But, whatever their truth, such claims commit the same sin as so many other Western narratives, claiming a universalism to which they have scant right. The implication that we are staring at an entire world bereft of the study of history, philosophy and literature – especially of the variety taught, researched and practised at universities – is unwarranted. As it happens, it is also false.

It is common knowledge in many academic circles that in Asia, the past decade has witnessed a resurgence of interest in the liberal arts – of which the humanities are certainly a key component, if not an exclusive one. Liberal arts colleges have sprouted and prospered during the 21st century in China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore. The same is true of India, from where I write.

Families, industrial groups and philanthropic collectives have set up private, non-profit liberal arts institutions with innovative curricula, pedagogy and research programmes. But the humanities have also been thriving in less obvious surroundings. Most striking are India’s key institutions of professional training.

Representative of the dream of development and upward mobility that has long obsessed the post-colonial nation, India’s elite institutes of technology and management are the last places you might consider when assessing the health or otherwise of the humanities. Yet in recent years, the nation – or at least, an elite class within it – has shown clear signs of fatigue with its modern fetish for professional and, especially, technocratic training.

The brainchildren of India’s first prime minister, the science- and research-focused Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian Institutes of Technology were always meant to go beyond mere technological competence, to create a holistically educated technocrat. Some were shaped after the vision of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which has always had a robust curriculum of humanities and social sciences, as illustrated by the celebrated linguists and economists who have graced its faculty. That vision has previously tended to fall by the wayside in the scramble for the quick socio-economic leg-up offered by an engineering degree from an elite institute. But this is now changing.

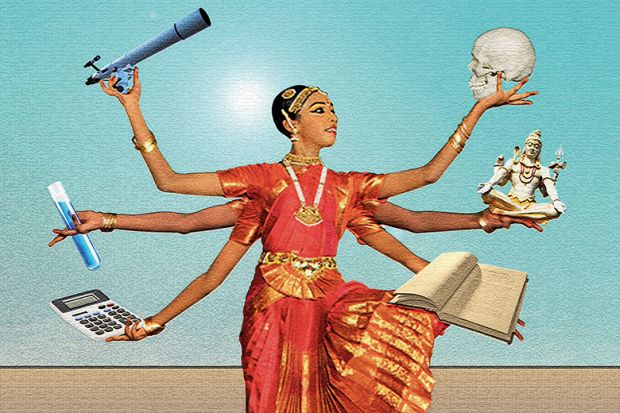

That fact has been revealed to me by the string of unexpected associations I have acquired with leading institutes of engineering and management since I published a book last year outlining a vision of liberal arts education in 21st-century India. Far more than the traditional universities of arts and sciences, these institutes have shown a keen interest in my vision of “contra-disciplinary” education, involving the curricular combination of qualitative and quantitative, “fuzzy” and “techie” fields, as a way of bolstering the high-powered engineering and management programmes that form the core of their educational visions. And, during my visits, I’ve learned much about how their holistic liberal arts curricula have been reinvigorated in a globalised, economically resurgent India, going far beyond their historical foundations.

Take, for instance, the newly endowed Partha S. Ghosh Academy of Leadership at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur. This institution plans to blend an innovative curriculum in the humanities – including ancient philosophy – with a core curriculum in engineering. According to the academy’s founding donor, Partha S. Ghosh, a US-based consultant and an IIT-Kharagpur alumnus, the motivation is to equip students to navigate anticipated fundamental shifts in the world economy in the near future, driven by a need to reinvent the foundations of capitalism. His explanation reminds me of an observation made a couple of years ago by Peter Salovey, who was then president of Yale University, about the Singapore government’s collaboration with Yale to set up the Yale-NUS liberal arts college. The government of the authoritarian state, he said (although it is easy to be sceptical about the claim), was looking to invest in a liberal education to prepare its citizens for the unprecedented experience of messy democracy.

India’s elite institutes of management have shown an even keener interest than their technological brethren in fundamental humanities and social sciences. I recently conducted a couple of workshops and panel discussions at the Indian Institute of Management, Indore. There, I learned about the institution’s five-year integrated programme in management initiated in 2011, which combines a three-year undergraduate education in the fundamental arts and sciences with a two-year MBA. The idea is to build professional training on a foundation of multidimensional breadth. It promises a 21st-century Asian articulation of a Peter Drucker-like vision of management studies, which enriches from a multidimensional humanistic consciousness. Similar programmes, I have learned, are also in the works at IIM Bangalore.

At an event discussing the liberal arts with a group of Mumbai physicians, I learned that Indian professional training has been restricted by the narrow colonial model of higher education, focused on training locals to work in the bureaucracy of the British Raj, just as much as arts and sciences education in India’s great public universities has been. According to Farokh Udwadia, the head of Breach Candy Hospital, the entrance examination for the MD training programme at the hospital is as narrow an exercise in rote learning as the clerically modelled examinations in English, philosophy or economics that determine university grades.

It was never as clear as it is today that both professional and non-vocational fields of study in India are crying out for a real shot of innovation. The enrichment of the professional with the liberal seems to be the ambitious yet necessary solution. Hence, it is only natural that, along with the fundamental sciences, the humanities have acquired a new urgency in at least one major jurisdiction beyond the usual Western purview.

Saikat Majumdar is professor of English and creative writing at Ashoka University. He is the author, most recently, of College: Pathways of Possibility (Bloomsbury India, 2018).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The new humanists

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?