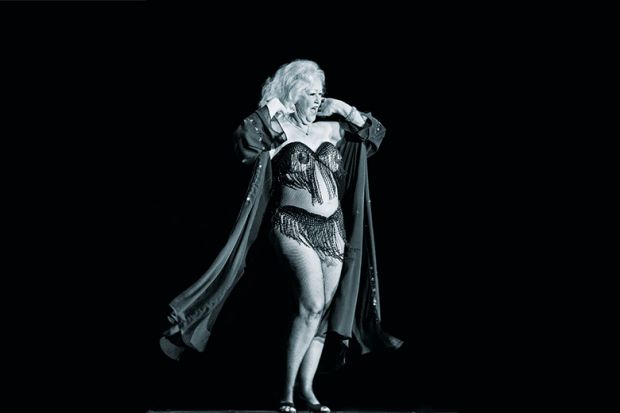

At the Legends of Burlesque Showcase at the Burlesque Hall of Fame Annual Weekender, 75-year-old Tammi True glides on to the stage and performs one of her traditional striptease numbers. She beams as she slowly caresses and sways her hips from side to side. She swivels, turns her back to the audience and attempts her signature move, bending over and looking between her legs while shaking her beaded panties. Although Tammi’s range of motion and ability to actually get her head between her legs are simply a nod towards what they used to be, the retro enthusiast audience of 800, mostly young women, cheer in anticipation of Tammi’s big reveal. Finally, after removing her bra, she stands with her arms in the air, belly out, joyously bouncing her pastie-clad, stage-veteran breasts and anything else that cares to bounce with them.

The crowd of neo-burlesque enthusiasts leap to their feet in outright celebration. Perhaps it is out of gratitude for the expression of freedom and defiance of common preconceptions of women’s bodies, particularly ageing ones. Perhaps they see the performance as a means to undermine the shaming that has been, and often still is, directed at sexually expressive women. Or perhaps they just really like it. One woman beside me dabs tears from her eyes; another, in front of me, pounds her fist in the air and exclaims, “Fuck, yeah!”

I first entered the Burlesque Hall of Fame community as a PhD student with a Samsung dictaphone and a few fervent notions about sex-positive feminism. I took a room at The Orleans in Las Vegas, a smoky, off-strip hotel that has been home to the Hall of Fame reunion for almost a decade. The community has its roots in an early sex-workers’ union, the Exotic Dancers League. The EDL’s first meeting, which the Los Angeles Times described as being “colorful but well-balanced” with “three redheads, three blonds, and three brunettes”, was held in June 1955, with the primary aim of raising the minimum wage for strippers in Los Angeles. The union employed a variety of unorthodox acts of protest to advance its cause, such as a “cover-up” strike. Eventually, however, the community took the form of a support group for dancers, and it established an annual meeting that continues today in Las Vegas. The reunion now operates as a social gathering space, where these late‑life entertainers perform their half-century-old routines to a rally of young burlesque fans.

Dating from the late 19th century, the American burlesque format consists of a succession of variety acts: most iconically, comics such as Charlie Chaplin and sequinned striptease dancers such as Gypsy Rose Lee and Tempest Storm. At the Burlesque Hall of Fame, those dancers who are still with us are lovingly referred to as “legends” – which, indeed, they are. Many were famed pin-ups. Some were stars of the early nudie films produced by Russ Meyer. Others were captured by tabloids for keeping the company of notable men such as Elvis Presley, John F. Kennedy and Duke Ellington.

By way of mid-20th-century erotica and its preserved ephemera – dog-eared posters, vintage men’s magazines and a few surviving cult classic B-movies – these legends have been seen. They have been seen, but they haven’t always been heard. This was the primary driving force behind the project I was working on. I hoped that with quality time spent in the community, we would develop relationships. I hoped that the dancers would grow comfortable with me. And, with this sense of comfort, they would in time share these previously untold stories.

But idealism and sisterhood aside, it was my role as presenter of a Canadian documentary series about burlesque called Revamped that afforded me initial access to the community. This fame factor (albeit Canadian C‑list fame) created a notable dynamic. Some women would speak to me out of interest in my supposed celebrity, while I questioned them about their former renown provided by the burlesque house and erotica industry. It seemed that my role as a “television personality” allowed participants to see beyond my academic persona; not uncommonly, they expressed a general dislike of academics, who had at times patronisingly championed their so-called liberated culture. As Jo “Boobs” Weldon, an exotic dancer turned headmistress of the New York School of Burlesque, once said to me, strippers don’t need the “approval of some PhD” to tell them whether they are empowered or not.

As I navigated this project, I heeded this warning and tried to play three roles of escalating importance: the academic, the presenter and the community member. This last role grew and strengthened over the years, enabling me to experience this social microcosm from within. Everything from discussing financial need to helping to stabilise an 85-year-old as she stepped into a sequinned G-string offered me a nuanced lens on both mid-20th-century burlesque culture and what it meant to be aged out of it. In the second and third years of my pilgrimages to Las Vegas, the photographer Matilda Temperley and the documentary-makers Nimisha Mukerji and Lindsay George joined me, allowing for film and photographic methodologies to further expand the project.

Burlesque has gone through a resurgence of late thanks to “neo-burlesque” – a young counterculture movement that has embraced and redefined this once working-class entertainment. This repopularisation has been tremendously positive for many of the women involved in the community. I sat with Toni Elling, named for her relationship to Duke Ellington, in a coffee shop in the foyer of The Orleans casino. Somehow, amid the constant clang of slot machines, it seemed very peaceful at our table. Toni gave a soft smile when I asked her about her career high. “This time,” she said. Right now, at the Burlesque Hall of Fame: “Who would think that 30-some years after quitting that someone would ask me to dance again, and it would go over as it has done? If anybody had told me in 1974 that that wasn’t the last show, I would have laughed. I couldn’t see myself at 80-some years old dancing. It just didn’t jibe.”

However, the framing of the Burlesque Hall of Fame event as a straightforward safe space is often an oversimplification. Unlike the neo-burlesque community, which is often recreational, work in the sex industry is regularly accompanied by complicating factors surrounding issues of need, survival and free choice. Jo’s warning is additionally significant in her use of the word “empowerment”. This is a term habitually employed by the neo-burlesque community, as it situates burlesque as a sex-positive, inclusive endeavour conducted in a safe space, and as an activity that – in contrast to (lowbrow) modern-day strip clubs – is (and always was) art.

Similarly, scholarly histories tend to date the “death” of American burlesque to the demise of the burlesque theatre at some point in the middle of the 20th century, disconnecting it from contemporary forms of exotic dance. Yet many interviews we conducted suggested that this performance form did not die, but rather lingers on, intersecting with other forms of sex work and erotic entertainments, spaces and timelines. The San Francisco-based dancer Holiday O’Hara remembered when her burlesque club made the transition from stage dance to lap dance in the 1980s. “In 1983, I quit, and the reason I quit was because they changed the format,” she stated frankly. “There was no opening and closing act. There was just girl after girl after girl. She’d dance for a heartbeat and then she’d crawl off the stage showing her pussy, getting money. They were basically dry humping people. Dry humping people for a dollar.”

The denial of this continuous history, in which dancers quite literally step off the stage and into the laps of patrons, is concerning in that it marginalises the women who did or do perform in these other forms of entertainments. Kitten Natividad, who transitioned from burlesque into pornography with the advent of VHS in the 1980s, explained: “I also did hardcore, and they [the community] almost make you feel like you sold your soul to the devil. But ask me if I give a fuck. I do what I do because I have to do it.”

Many legends suggest that glamorising burlesque’s history can trivialise the difficult realities experienced. “To glorify [burlesque] is kind of silly”, Bic Carrol declared. “It was a way to make money. It was a job. It wasn’t a hobby. To [the neo-burlesque community] it’s a hobby. To us, it was survival.”

This survival at times led to emotional detachment or substance misuse, as dancers were often asked to step over lines that they had drawn for themselves. As they moved from stage to lap, some dancers spoke of a perceived demotion in status or a struggle to remain “classy”. Others found the boundaries between performer and sex worker harder to maintain. Many spoke of heightened expectations under tables or in dark corners. A few recalled mob violence or physical abuse. Kitten discussed the Aids epidemic, which emerged while she was performing in pornographic film.

It was through these stories, where “performances” had such real implications, that I began to question if exotic entertainment could ever be removed from its complex reality. And with that, the reimaginings of this history – where feather boas and thigh-high stockings are equated with empowerment and personal agency – become problematic, as these nostalgic framings can downplay the countless accounts of abuse, sexual violence and exploitation voiced by the legends.

The morning after Tammi’s performance at the Legends of Burlesque Showcase, I sat in an Orleans conference room for the Legends Panel. Beside a breakfast table of cellophane-wrapped croissants and Minute Maid orange juice, a line of about 20 legends answered questions posed by the audience. One audience member dressed in 1950s-inspired clothing and sporting the traditional rebellious body art of the neo-burlesque community asked: “Did you ladies consider yourselves feminist?” The panel was silent, and the convener repeated the question. After another pause, one legend, sporting large sunglasses and leopard-print loungewear, sarcastically rebuffed the question: “Honey, they may have been burning their bras [in the 1960s], but we were taking [ours] off way before that.”

I have presented television programming on the liberated cultural history of burlesque. I have a podcast that passionately situates pleasure and sexual agency as a cornerstone of the contemporary women’s movement. And, just like the neo-burlesquer in the retro clothing, I entered the Burlesque Hall of Fame community with a hope of interpreting these legends as the unsung feminists of the 20th century.

More often than not, however, they were not interested in being labelled as such. Some dancers, particularly those who had been performing in the 1950s and then witnessed the birth of the women’s movement, felt that feminism had had a negative impact on their careers. Marinka, a Spanish-born dancer, explained that a group of students in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had conducted a daily picketing of the theatre in which she was dancing, chanting: “burn the bra, equality and this and that and the other…I never wanted after that to go back to that town. I didn’t like that town at all. But things like that were happening in the ’60s.”

The legends and their careers exist in a tension-filled space within the history of the women’s movement and are a continuing reminder of the need for intersectional feminism (recognising that various forms of discrimination are interconnected). As these dancers speak of fighting to be “classy”, they raise questions of class and opportunity. They blur lines between performer and sex worker. And in doing so, they disrupt established timelines, industries and identities. As a result, these stories need to be told in a way that honours their multitude of identities – artist, sex worker, working class, “classy”, feminist or decidedly pre-feminist.

It was in a supposed “death” period that the legends lived. Their experiences reflect a point of transition when many dancers moved from decrepit burlesque theatres to tiered travelling shows, to sometimes soulless strip clubs, to potentially dangerous pornographic film sets – and, at times, back and forth between them. In the end, I sought to represent this history in the manner in which it was told to me – multifaceted and messy.

My interest is in the telling of stories: both what we tell and how we tell it. My current work investigates online misogyny. I’ve written on this topic with Jessica Ringrose of the UCL Institute of Education. We are now developing a school-based project on young masculinities and social media. This project engages with young people’s stories and experiences online and uses digital storytelling and film-making to interrupt sexual violence in youth relationship cultures.

Both projects are, of course, about gender and cultural politics, but they also share methodological tools. I’m drawn to film and photography because they allow review by researchers and participants, which can help to increase the scope of interpretation. Throughout my five years in Vegas, I was fortunate to have shared greasy meals and discount hotel rooms with Matilda, Lindsay and Nimisha, who were constant sounding boards and collaborative counterparts for me. These talented women served as the eyes of the project and allowed for much more nuanced coverage of experiences. Indeed, this is a virtue of film in general. And it is from this place of complexity that people and communities can be both seen and heard most fully. For, as Bic would argue, “To glorify [burlesque] is kind of silly.” These stories are about survival. And, thus, they are at their most essential when told with all their disrupted timelines, sequins and struggle, glitter and grit.

Kaitlyn Regehr is cultural and gender theorist and lecturer in media studies at the University of Kent. This article contains sections from her book with photographer Matilda Temperley, The League of Exotic Dancers: Legends from American Burlesque, published by Oxford University Press. The images are taken from the book and from her documentary feature film that derived from the project, Tempest Storm.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Show and tell

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?