In 2008, the US financier Jeffrey Epstein was convicted of soliciting prostitution with a minor. However, he served only 13 months, largely on “work release”. He had friends in high places, including Bill Clinton and, of course, Prince Andrew.

If Epstein had been convicted in the UK, he would have served a longer sentence. There would have been no chance that Prince Andrew could have stayed with him for four days within two years of his conviction unless it had literally been “at Her Majesty’s pleasure”.

But if UK judges are made of rather sterner stuff than their US equivalents, the same cannot be said of UK universities and academic journals.

In 2015, for instance, a journal turned down an article of mine that addressed Prince Andrew’s behaviour in the context of wider issues around sexual abuse. The stated reason was that the article was “not saying anything we did not already know”. But while it is true that the British media had already reported on Prince Andrew’s behaviour with Epstein, via interviews with his security team, few academics had written about it.

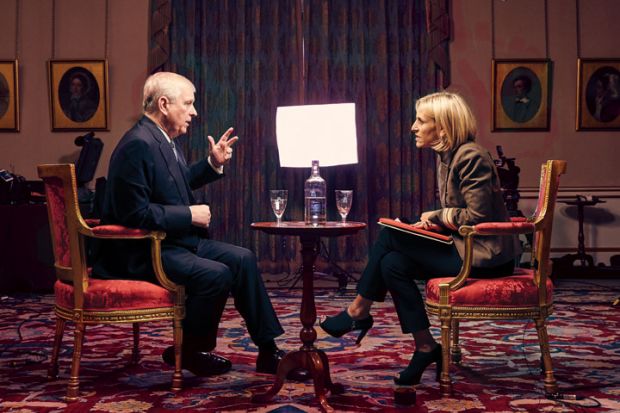

Moreover, if the story were so well known four years ago, why is it only in the wake of the Prince’s disastrous recent Newsnight interview that he was forced to relinquish all his public roles?

Fear of libel action is, of course, very real, with UK law notably stricter in this area than US law. While mass-circulation newspapers can afford to run calculated risks, the cost of defending a libel action could ruin an academic publisher. In 2016, for instance, another publisher spent £2,000 on a legal reading of one of my books, due, in part, to my mentioning the royals in a somewhat contentious context.

Playing safe, some might say, is the nature of academia, especially academic publishing. Others might add that this is only exacerbated by the influence of the honours system on university governance. While governors have no formal influence on what academics research, their disproportionate likelihood to have an OBE or CBE means that they are hardly likely to encourage their institutions to push the envelope when it comes to probing the Establishment’s misdeeds.

Whatever the reasons, the fact is that academic discourse on the royals is severely limited. There are few books and journals that address it, or go beyond the myths. Researchers are more comfortable discussing royals who died 400 years ago; investigating the connections between Epstein and the man who is currently eighth in line to the British throne is left to the scorned tabloids.

Yet it is absurd, in these times of higher scrutiny and criticism, for academics and their publishers to fail to engage in discourse that tackles the misdemeanours of powerful people. Media and communication studies should have a lot more to say on the issue, but so should the wider humanities, as well as politics and law.

Of course, no one should be on trial by public opinion. Yet the fact is that the British public funds the royals: their every home improvement, luxury trip and PR nightmare. So their behaviour is very much a matter of public interest.

Do the latest revelations make the slightest difference to public attitudes towards the monarchy? A 2017 YouGov poll put the Queen’s popularity at 73 per cent, the highest of any comparable monarch in the world. Transgressions can have some impact, but who would seriously sack the Queen at the age of 93? When it comes to her eldest son, however, the question has more resonance. The forthcoming film The Man Who Shouldn’t Be King attacks Prince Charles for a number of reasons, including his finances.

Is Prince Andrew’s car crash interview part of a pattern of royal mistakes, alongside Prince Philip’s delay in apologising for causing a literal car crash earlier this year, as well as the Queen’s agreeing to Boris Johnson’s request to prorogue Parliament, despite the courts’ subsequently ruling that it was illegal; and Prince Harry’s apparent exposure of a rift with his brother, Prince William? The normally pro-monarchy media suggest that the Queen is losing control, with the implication that she should take a tighter grip, while the UK would be better off with a written constitution.

Whatever your view, all this is undeniably relevant in our current social and political predicament, and would benefit from rigorous academic analysis. We should not be leaving it all up to journalists.

Jason Lee is professor of film, media and culture at De Montfort University and a chartered psychologist. He is the author of three books on child sexual abuse and popular culture and the editor of the book series Transgressive Media Culture with Amsterdam University Press.

后记

Print headline: Crown and gown