Inhalable oxytocin

Life-saving aid for the midwife’s kit

A new approach for controlling haemorrhaging during childbirth could save the lives of thousands of mothers in developing countries.

Death during childbirth as a consequence of unchecked postpartum haemorrhage unfortunately remains a significant risk for many women, despite it being readily preventable with an injection of the hormone oxytocin.

Frustratingly, this life-saving measure, which stems excessive blood loss, is largely accessible only in developed countries, as oxytocin must be kept in cold storage and injected by trained medical staff using sterile syringes. Consequently, most of the 120,000 to 150,000 mothers reported to die each year from bleeding after delivery are in poor, remote communities that lack the necessary facilities and expertise.

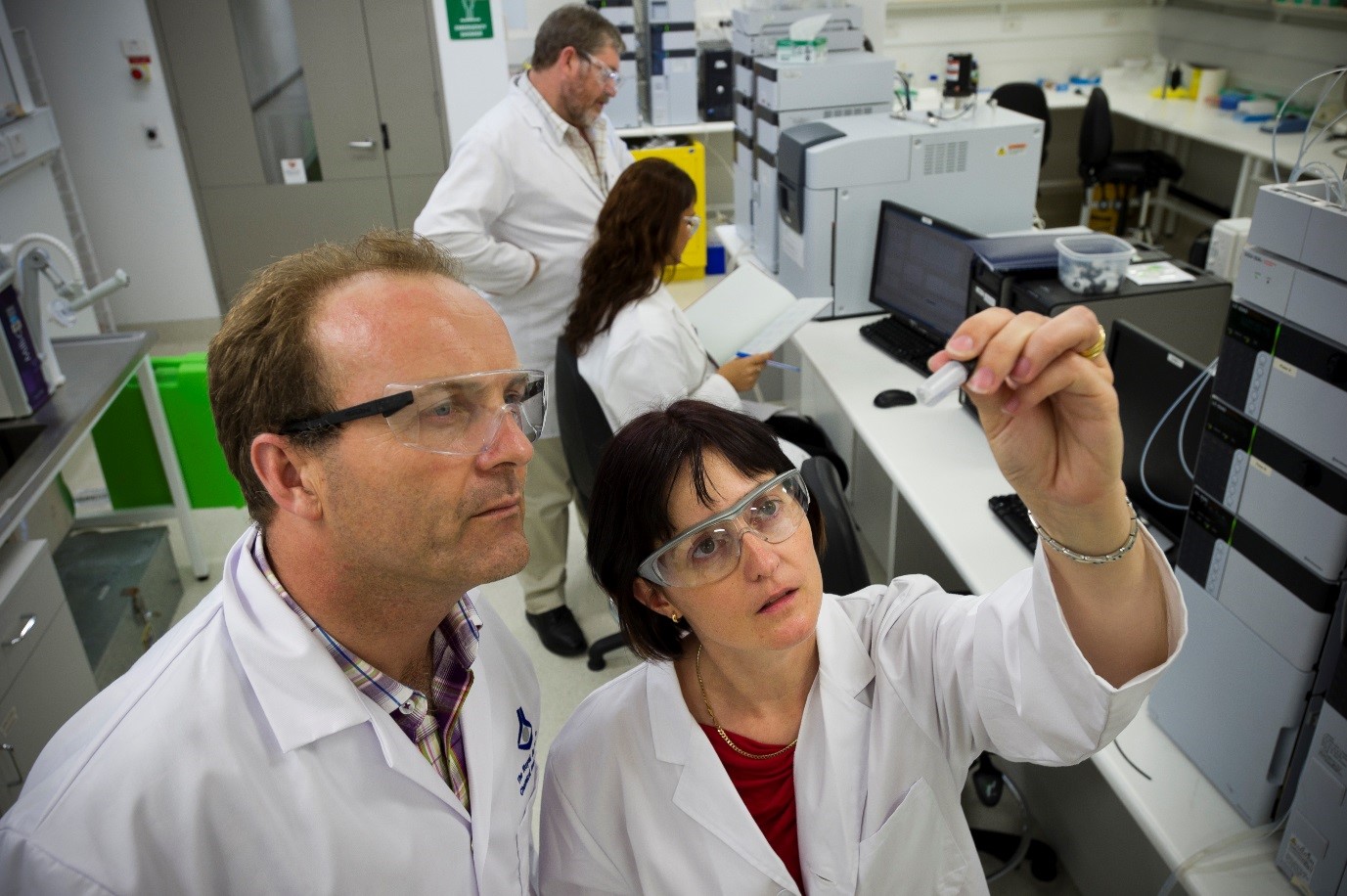

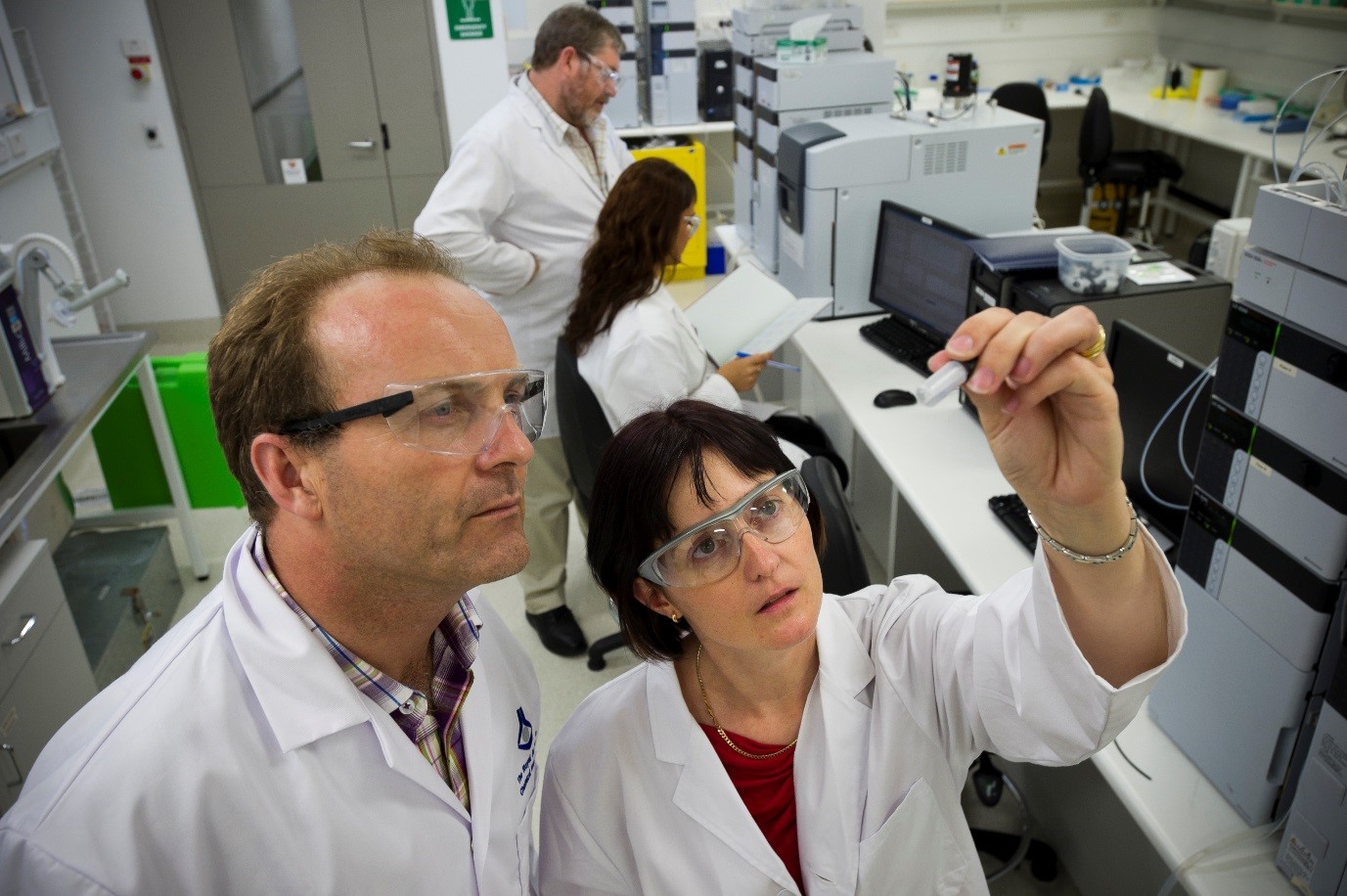

To improve the outlook for women in these poorer communities, Monash University researchers, led by Dr Michelle McIntosh, are developing an inhalable formulation of oxytocin. Stable at room temperature and resistant to degradation by heat or humidity, it will be administered through a simple inhaler that can be used with minimal training.

Many women in the developing world give birth at home and have no access to medical services. The nearest hospital may be hours or even days away, and there’s no guarantee it will be adequately staffed, or have an oxytocin supply that has been stored correctly and clean syringes with which to inject the drug.

Making an oxytocin inhaler a standard part of every midwife’s bag, or including one in a safe birthing kit given to all expectant mothers, could be the difference between life and death for hundreds of thousands of women, who would use the inhaler immediately after birth to prevent haemorrhage.

As well as engineering the oxytocin powder, the Monash team wants to ensure women will be happy using the inhaler.

“Some of our biggest challenges are going to be around the fact that women in developing countries are not necessarily as familiar with inhaled delivery as we are,” says Dr McIntosh, a senior lecturer at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS).

There is a cultural perception, particularly in the developing world, that an injection is “strong medicine”. Inhalers are a rare sight.

“Are they going to think that this medicine is not real, or not trust the medicine because it’s a different way of delivering it?” Dr McIntosh asks.

To answer that question, the team has talked to healthcare workers, midwives and women in rural areas in India and Uganda. The feedback has been encouraging, she says, with responses such as: “If you teach us how to use it, we’ll use it.”

“They’re not worried about the device; it just needs to be simple,” Dr McIntosh says.

The team is seeking funding for stage-one clinical trials, to be conducted in Australia. Further clinical trials will examine use of the inhaler by the intended users – women in rural areas of countries such as India, Uganda and Papua New Guinea. The project has already received funding and recognition from the World Health Organisation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the international partnership Saving Lives at Birth.

“Sometimes it feels like we’ve got to work faster,” Dr McIntosh says. “There’s a lot of pressure, but there’s also the opportunity to be involved in something that makes a difference.”